“I’ll announce myself,” the king said to the guard at her door and stepped in without ceremony.

Lady Margaret was seated at a table in the window, the household accounts spread before her, inspecting the costs of the royal court as if it were a well-run farm. There was very little waste and no extravagance allowed in the court run by Lady Margaret, and royal servants who had thought that some of the payments which passed through their hands might leave a little gold on the side were soon disappointed.

Henry nodded his approval at the sight of his mother’s supervision of the royal business. He had never rid himself of his own anxiety that the ostentatious wealth of the throne of England might prove to be hollow show. He had financed a campaign for the throne on debt and favors; he never wanted to be cap in hand again.

She looked up as he came in. “My son.”

He kneeled for her blessing, as he always did when he first greeted her every day, and felt her fingers gently touch the top of his head.

“You look troubled,” she remarked.

“I am,” he said. “I went to see the Dowager Princess.”

“Yes?” A faint expression of disdain crossed her face. “What are they asking for now?”

“We—” He broke off and then started again. “We have to decide what is to become of her. She spoke of going home to Spain.”

“When they pay us what they owe,” she said at once. “They know they have to pay the rest of her dowry before she can leave.”

“Yes, she knows that.”

There was a brief silence.

“She asked if there could not be another agreement,” he said. “Some resolution.”

“Ah, I’ve been waiting for this,” Lady Margaret said exultantly. “I knew they would be after this. I am only surprised they have waited so long. I suppose they thought they should wait until she was out of mourning.”

“After what?”

“They will want her to stay,” she said.

Henry could feel himself beginning to smile and deliberately he set his face still. “You think so?”

“I have been waiting for them to show their hand. I knew that they were waiting for us to make the first move. Ha! That we have made them declare first!”

He raised his eyebrows, longing for her to spell out his desire. “For what?”

“A proposal from us, of course,” she said. “They knew that we would never let such a chance go. She was the right match then, and she is the right match now. We had a good bargain with her then, and it is still good. Especially if they pay in full. And now she is more profitable than ever.”

His color flushed as he beamed at her. “You think so?”

“Of course. She is here, half her dowry already paid, the rest we have only to collect. We have already rid ourselves of her escort. The alliance is already working to our benefit—we would never have the respect of the French if they did not fear her parents; the Scots fear us too—she is still the best match in Christendom for us.”

His sense of relief was overwhelming. If his mother did not oppose the plan, then he felt he could push on with it. She had been his best and safest advisor for so long that he could not have gone against her will.

“And the difference in age?”

She shrugged. “It is…what? Five, nearly six years? That is nothing for a prince.”

He recoiled as if she had slapped him in the face. “Six years?” he repeated.

“And Harry is tall for his age and strong. They will not look mismatched,” she said.

“No,” he said flatly. “No. Not Harry. I did not mean Harry. I was not speaking of Harry!”

The anger in his voice alerted her. “What?”

“No. No. Not Harry. Damn it! Not Harry!”

“What? Whatever can you mean?”

“It is obvious! Surely it is obvious!”

Her gaze flashed across his face, reading him rapidly, as only she could. “Not Harry?”

“I thought you were speaking of me.”

“Of you?” She quickly reconsidered the conversation. “Of you for the Infanta?” she asked incredulously.

He felt himself flush again. “Yes.”

“Arthur’s widow? Your own daughter-in-law?”

“Yes! Why not?”

Lady Margaret stared at him in alarm. She did not even have to list the obstacles.

“He was too young. It was not consummated,” he said, repeating the words that the Spanish ambassador had learned from Doña Elvira, which had been spread throughout Christendom.

She looked skeptical.

“She says so herself. Her duenna says so. The Spanish say so. Everybody says so.”

“And you believe them?” she asked coldly.

“He was impotent.”

“Well…” It was typical of her that she said nothing while she considered it. She looked at him, noting the color in his cheeks and the trouble in his face. “They are probably lying. We saw them wedded and bedded and there was no suggestion then that it had not been done.”

“That is their business. If they all tell the same lie and stick to it, then it is the same as the truth.”

“Only if we accept it.”

“We do,” he ruled.

She raised her eyebrows. “It is your desire?”

“It is not a question of desire. I need a wife,” Henry said coolly, as though it could be anyone. “And she is conveniently here, as you say.”

“She would be suitable by birth,” his mother conceded, “but for her relationship to you. She is your daughter-in-law even if it was not consummated. And she is very young.”

“She is seventeen,” he said. “A good age for a woman. And a widow. She is ready for a second marriage.”

“She is either a virgin or she is not,” Lady Margaret observed waspishly. “We had better agree.”

“She is seventeen,” he corrected himself. “A good age for marriage. She is ready for a full marriage.”

“The people won’t like it,” she observed. “They will remember her wedding to Arthur, we made such a show of it. They took to her. They took to the two of them. The pomegranate and the rose. She caught their fancy in her lace mantilla.”

“Well, he is dead,” he said harshly. “And she will have to marry someone.”

“People will think it odd.”

He shrugged. “They will be glad enough if she gives me a son.”

“Oh, yes, if she can do that. But she was barren with Arthur.”

“As we have agreed, Arthur was impotent. The marriage was not consummated.”

She pursed her lips but said nothing.

“And it gains us the dowry and removes the cost of the jointure,” he pointed out.

She nodded. She loved the thought of the fortune that Catalina would bring.

“And she is here already.”

“A most constant presence,” she said sourly.

“A constant princess.” He smiled.

“Do you really think her parents would agree? Their Majesties of Spain?”

“It solves their dilemma as well as ours. And it maintains the alliance.” He found he was still smiling, and tried to make his face stern, as normal. “She herself would think it was her destiny. She believes herself born to be Queen of England.”

“Well then, she is a fool,” his mother remarked smartly.

“She was raised to be queen since she was a child.”

“But she will be a barren queen. No son of hers will be any good. He could never be king. If she has one at all, he will come after Harry,” she reminded him. “He will even come after Harry’s sons. It’s a far poorer alliance for her than marriage to a Prince of Wales. The Spanish won’t like it.”

“Oh, Harry is still a child. His sons are a long way ahead. Years.”

“Even so. It would weigh on her parents. They will prefer Prince Harry for her. That way, she is queen and her son is king after her. Why would they agree to anything less?”

Henry hesitated. There was nothing he could say to fault her logic, except that he did not wish to follow it.

“Oh. I see. You want her,” she said flatly when the silence extended so long that she realized there was something he could not let himself say. “It is a matter of your desire.”

He took the plunge. “Yes,” he confirmed.

Lady Margaret looked at him with calculation in her gaze. He had been taken from her as little more than a baby for safekeeping. Since then she had always seen him as a prospect, as a potential heir to the throne, as her passport to grandeur. She had hardly known him as a baby, never loved him as a child. She had planned his future as a man, she had defended his rights as a king, she had mapped his campaign as a threat to the House of York—but she had never known tenderness for him. She could not learn to feel indulgent towards him this late in her life; she was hardly ever indulgent to anyone, not even to herself.

“That’s very shocking,” she said coolly. “ I thought we were talking of a marriage of advantage. She stands as a daughter to you. This desire is a carnal sin.”

“It is not and she is not,” he said. “There is nothing wrong in honorable love. She is not my daughter. She is his widow. And it was not consummated.”

“You will need a dispensation. It is a sin.”

“He never even had her!” he exclaimed.

“The whole court put them to bed,” she pointed out levelly.

“He was too young. He was impotent. And he was dead, poor lad, within months.”

She nodded. “So she says now.”

“But you do not advise me against it,” he said.

“It is a sin,” she repeated. “But if you can get dispensation and her parents agree to it, then—” She pulled a sour face. “Well, better her than many others, I suppose,” she said begrudgingly. “And she can live at court under my care. I can watch over her and command her more easily than I could an older girl, and we know that she behaves herself well. She is obedient. She will learn her duties under me. And the people love her.”

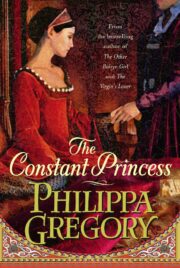

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.