I cannot bear to tell them the truth: I am barren, without a baby to raise for him. And while I say nothing, they have to wait too. They will not send me home to Spain while they hope that I might still be My Lady the Mother of the Prince of Wales. They have to wait.

And while they wait, I can plan what I shall say and what I shall do. I have to be wise as my mother would be and cunning as the fox, my father. I have to be determined like her and secretive like him. I have to think how and when I shall start to tell this lie, Prince Arthur’s great lie. If I can tell it so that it convinces everyone, if I can place myself so that I fulfill my destiny, then Arthur, beloved Arthur, can do as he wished. He can rule England through me, I can marry his brother and become queen. Arthur can live through the child I conceive with his brother. We can make the England we swore that we would make, despite misfortune, despite his brother’s folly, despite my own despair.

I shall not give myself to heartbreak, I shall give myself to England. I shall keep my promise. I shall be constant to my husband and to my destiny. And I shall plan and plot and consider how I shall conquer this misfortune and be what I was born to be. How I shall be the pretender who becomes the queen.

London,

June 1502

THE LITTLE COURT MOVED TO DURHAM HOUSE in late June and the remainder of Catalina’s court straggled in from Ludlow Castle, speaking of a town in silence and a castle in mourning. Catalina did not seem particularly pleased at the change of scene, though Durham House was a pretty palace with lovely gardens running down to the river, with its own stairs and a pier for boats. The ambassador came to visit her and found her in the gallery at the front of the house, which overlooked the front courtyard below and Ivy Lane beyond.

She let him stand before her.

“Her Grace, the queen your mother, is sending an emissary to escort you home as soon as your widow’s jointure is paid. Since you have not told us that you are with child she is preparing for your journey.”

De Puebla saw her press her lips together as if to curb a hasty reply. “How much does the king have to pay me, as his son’s widow?”

“He has to pay you a third of the revenues of Wales, Cornwall and Chester,” he said. “And your parents are now asking, in addition, that King Henry return all of your dowry.”

Catalina looked aghast. “He never will,” she said flatly. “No emissary will be able to convince him. King Henry will never pay such sums to me. He didn’t even pay my allowance when his son was alive. Why should he repay the dowry and pay a jointure when he has nothing to gain from it?”

The ambassador shrugged his shoulders. “It is in the contract.”

“So too was my allowance, and you failed to make him pay that,” she said sharply.

“You should have handed over your plate as soon as you arrived.”

“And eat off what?” she blazed out.

Insolently, he stood before her. He knew, as she did not yet understand, that she had no power. Every day that she failed to announce that she was with child her importance diminished. He was certain that she was barren. He thought her a fool now: she had bought herself a little time by her discretion—but for what? Her disapproval of him mattered very little; she would soon be gone. She might rage but nothing would change.

“Why did you ever agree to such a contract? You must have known he would not honor it.”

He shrugged. The conversation was meaningless. “How should we think there would ever be such a tragic occurrence? Who could have imagined that the prince would die, just as he entered into adult life? It is so very sad.”

“Yes, yes,” said Catalina. She had promised herself she would never cry for Arthur in front of anyone. The tears must stay back. “But now, thanks to this contract, the king is deep in debt to me. He has to return the dowry that he has been paid, he cannot have my plate, and he owes me this jointure. Ambassador, you must know that he will never pay this much. And clearly he will never give me the rents of—where?—Wales and, and Cornwall?—forever.”

“Only until you remarry,” he observed. “He has to pay your jointure until you remarry. And we must assume that you will remarry soon. Their Majesties will want you to return home in order to arrange a new marriage for you. I imagine that the emissary is coming to fetch you home just for that. They probably have a marriage contract drawn up for you already. Perhaps you are already betrothed.”

For one moment de Puebla saw the shock in her face, then she turned abruptly from him to stare out of the window on the courtyard before the palace and the open gates to the busy streets outside.

He watched the tightly stretched shoulders and the tense turn of her neck, surprised that his shot at her second marriage had hit her so hard. Why should she be so shocked at the mention of marriage? Surely she must know that she would go home only to be married again?

Catalina let the silence grow as she watched the street beyond the Durham House gate. It was so unlike her home. There were no dark men in beautiful gowns, there were no veiled women. There were no street sellers with rich piles of spices, no flower sellers staggering under small mountains of blooms. There were no herbalists, physicians, or astronomers, plying their trade as if knowledge could be freely available to anyone. There was no silent movement to the mosque for prayer five times a day, there was no constant splash of fountains. Instead there was the bustle of one of the greatest cities in the world, the relentless, unstoppable buzz of prosperity and commerce and the ringing of the bells of hundreds of churches. This was a city bursting with confidence, rich on its own trade, exuberantly wealthy.

“This is my home now,” she said. Resolutely she put aside the pictures in her mind of a warmer city, of a smaller community, of an easier, more exotic world. “The king should not think that I will go home and remarry as if none of this has happened. My parents should not think that they can change my destiny. I was brought up to be Princess of Wales and Queen of England. I shall not be cast off like a bad debt.”

The ambassador, from a race who had known disappointment, so much older and wiser than the girl who stood at the window, smiled at her unseeing back. “Of course it shall be as you wish,” he lied easily. “I shall write to your father and mother and say that you prefer to wait here, in England, while your future is decided.”

Catalina rounded on him. “No, I shall decide my future.”

He had to bite the inside of his cheeks to hide his smile. “Of course you will, Infanta.”

“Dowager Princess.”

“Dowager Princess.”

She took a breath; but when it came, her voice was quite steady. “You may tell my father and mother, and you shall tell the king, that I am not with child.”

“Indeed,” he breathed. “Thank you for informing us. That makes everything much clearer.”

“How so?”

“The king will release you. You can go home. He would have no claim on you, no interest in you. There can be no reason for you to stay. I shall have to make arrangements but your jointure can follow you. You can leave at once.”

“No,” she said flatly.

De Puebla was surprised. “Dowager Princess, you can be released from this failure. You can go home. You are free to go.”

“You mean the English think they have no use for me?”

He gave the smallest of shrugs, as if to ask: what was she good for, since she was neither maid nor mother?

“What else can you do here? Your time here is over.”

She was not yet ready to show him her full plan. “I shall write to my mother,” was all she would reply. “But you are not to make arrangements for me to leave. It may be that I shall stay in England for a little while longer. If I am to be remarried, I could be remarried in England.”

“To whom?” he demanded.

She looked away from him. “How should I know? My parents and the king should decide.”

I have to find a way to put my marriage to Harry into the mind of the king. Now that he knows I am not with child surely it will occur to him that the resolution for all our difficulties is to marry me to Harry?

If I trusted Dr. de Puebla more, I should ask him to hint to the king that I could be betrothed to Harry. But I do not trust him. He muddled my first marriage contract, I don’t want him muddling this one.

If I could get a letter to my mother without de Puebla seeing it, then I could tell her of my plan, of Arthur’s plan.

But I cannot. I am alone in this. I do feel so fearfully alone.

“They are going to name Prince Harry as the new Prince of Wales,” Doña Elvira said quietly to the princess as she was brushing her hair in the last week of June. “He is to be Prince Harry, Prince of Wales.”

She expected the girl to break down at this last severing of her links with the past, but Catalina did nothing but look around the room. “Leave us,” she said shortly to the maids who were laying out her nightgown and turning down the bed.

They went out quietly and closed the door behind them. Catalina tossed back her hair and met Doña Elvira’s eyes in the mirror. She handed her the hairbrush again and nodded for her to continue.

“I want you to write to my parents and tell them that my marriage with Prince Arthur was not consummated,” she said smoothly. “I am a virgin as I was when I left Spain.”

Doña Elvira was stunned, the hairbrush suspended in midair, her mouth open. “You were bedded in the sight of the whole court,” she said.

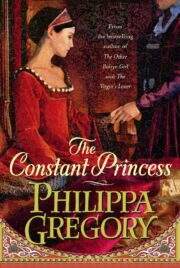

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.