'We were on pilgrimage to Compostella, to pray for her mother's soul. She hated travelling. It was only because it was her duty… her accursed duty.' Benedict's eyes burned and filled. He looked through a polish of tears at the Moor. 'I was with her; she thought that she was safe.'

'Do you desire to speak to a priest for comfort?'

'No!' Benedict almost choked on the word. 'That is the last thing I want to do.' He bit his lip, struggling for control, and when he had mastered himself, looked at the physician, who was eyeing him the way he might eye a strange creature in a cage. 'I want to sit up, but I cannot move.'

'Small wonder, the size of the hole in your side. Allah be praised that the arrow did not pierce a fraction deeper, or you would now be dead.'

'Allah be praised?' There was a note of cynicism in Benedict's voice. Just now he was not sure whether living was a blessing or a curse.

'Allah be praised,' Faisal ibn Mansour repeated firmly, and grasping him by the right arm, manipulated him gently upright, supporting his spine with more pillows. The pain was briefly blinding and it took Benedict a moment to recover, leaning back, his eyes tightly closed. When he opened them once more, the older man was staring at him curiously, his hands folded within his sleeves.

'You see that you are wearing nought but a loin cloth,' he said. 'That is to help your wounds heal. If you wish to leave your bed, clothes can be found for you. Your tunic, the one you were wearing when we fished you out of the river, is locked in the chest in my chamber. If you had a money pouch, I fear it has been robbed.'

Benedict's gaze sharpened. The pain had sufficiently diminished for him to be aware of the reason for the Moor's curiosity. It was not every pilgrim who carried a fortune in silver sewn into the lining of his tunic. 'I did have a money pouch,' he said slowly, 'with enough in it to give alms to the poor and pay out for our board and lodging where necessary, but as you have realised, that is not where the bulk of my wealth was stored.'

The physician unfolded his hands from his robe and went to the cupboard, returning with a jug of wine and a cup. He filled one from the other. 'Drink,' he commanded. 'You must restore your strength.'

Benedict took several swallows, and rested his head against the heavily stuffed pillows. His left arm and side throbbed painfully. 'How long have I lain here?'

'You have been three days on the road, and three days in this bed. This morning is the fourth.'

Benedict tried to order his thoughts. It seemed as if eternity had passed since the attack, and conversely, no time at all. 'My wife,' he said hesitantly, 'and the others. What happened to them… I mean, what did you do?'

Faisal spread apologetic hands. 'We were only a small party, we could not carry them with us, but we composed the bodies decently, and spoke to a priest as soon as we met habitation. He promised that he would attend to the matter of their burial. I will take you to the village when you are recovered, if you wish.'

'Thank you.'

Faisal cocked his head on one side. 'We still do not know your name, or how we should address you. Outside this room, they call you the Young Frank, but there is more to you than that, I think.'

Benedict's mouth curved in a bleak half-smile. 'I prefer the simplicity of being "the Young Frank",' he said, 'but if you desire to know my name I will tell you. I am Benedict de Remy and I call Normandy and England my home. My father is a prosperous wine-merchant, and my father-in-law breeds horses for the Duke of Normandy and the King of England.'

'Ah,' said Faisal, looking interested, but not particularly impressed. A man, as El Cid was always saying, should be judged on what he is, not who his forefathers were. Although a breeder of horses might take exception to that theory. 'But what of yourself?' he asked.

The half-smile deepened. 'I would not blame you if you thought I had been sent on a pilgrimage to stiffen my character -it is something that rich fathers do for their decadent sons.'

'I make no such judgements. Only Allah sees what is in a man's heart.'

Benedict shrugged, not entirely in agreement, but did not argue the point. 'You ask what of myself,' he said after a moment. 'The easiest reply is that I too breed horses, that I am an assistant to my father-in-law. My wife came here to visit the shrine of St James at Compostella, and I elected to escort her because I wanted to buy Spanish horses to improve our bloodstock in the north. It is my desire to breed the best warhorses in the Christian world.'

'Even if the best warhorses of the moment are Moslem bred?' Faisal asked mischievously.

Benedict smiled. 'I am willing to learn. A man's religion should not stand in the way of knowledge.'

Faisal nodded with cautious approval. 'When you are well, will you still pursue your intention?'

Benedict closed his eyes for a moment, mustering his strength. 'If I do not, then everything will have been wasted. No matter how much I want to crawl into a corner and cover my head, it is no respect to the dead to live a life of mourning. I will still go to Compostella, and fulfil her vow, and I will still find my horses.'

Faisal pursed his lips and nodded slowly. 'That is good,' he pronounced. After a pause, he added, 'When we found your wife, she was still clutching a reliquary in her hand. That too is in my coffer with your tunic. I know that you Christians set great store by the relics of their saints.'

'Some of us,' Benedict said, and his voice was tired and bitter. 'Gisele believed that they would take her unharmed through fire and flood. I was the unbeliever, and yet I survive. Perhaps, as they say, the devil looks after his own.'

CHAPTER 55

The interior of the tiny chapel glowed like a jewel. Slender wax tapers twinkled in pyramid clusters, lighting the cool stone darkness, giving the pilgrim a feeling of intimacy with God. Upon the altar, a cross of inlaid silver-gilt reflected the flames until its surface rippled like water. A statue of the Virgin Mary, blue-robed and serene, smiled down upon the worshippers. A plump Christ child sat in the crook of her arm and raised his painted wooden hand in blessing to all who knelt before him. At his mother's feet lay a treasure house of pilgrim offerings, from simple wreaths of flowers and cheap tokens in plaster and wood, to bracelets and crosses of silver and bronze inlaid with semiprecious stones, belts and cups, and even a carved cedarwood box containing myrrh.

Benedict knelt before the silver-gilt cross and the statue with its improbably coloured pink flesh. The stone floor was cold beneath his knees; the scar in his side was sore from the strain of riding and then kneeling. It was less than a week since he had risen from his sick bed, and he knew that he had pushed himself too fast and too far in his need to make atonement at the place where Gisele was buried.

He tried to concentrate on the chapel's gentle atmosphere rather than his own aches and pains, to project himself beyond the mire of the physical. Ave Maria, Regina caelorum, Beata Maria… The Virgin's smile filled his vision. He clutched Gisele's small reliquary in his hand, his thumb moving over its edges, the raised cold bumps of agate and emerald. He was going to leave her here, in this small, intimate hamlet on the road to Compostella. Every day pilgrims would come to pray. If her spirit chose to linger, she would not be lonely. He could not bear the thought of disinterring her body and bearing it home to England. Mile after mile it would drag like a lead shackle upon his conscience. Let her lie here, undisturbed. Benedicte.

Behind him, someone gently cleared his throat. Turning, he saw the soldier, Angel. Hat in hand, the man knelt before the altar, genuflected to the statue, then addressed Benedict in a hushed voice. 'I am sorry to disturb you, Seсor, but Lord Faisal says that if you have had enough time, we must be riding on to reach our destination before dark.'

Benedict looked down at the small box in his hand. 'I am ready,' he said, and rising stiffly to his feet, stepped forward to the statue and laid the reliquary at its feet. It belonged to Gisele, was no part of him. He remembered the look on her face when she first held it in her hands, the hunger; the wondering delight that such an object could actually exist and belong to her. He crossed himself once more, and then turned and walked out of the chapel without looking back. Nor did he visit the graveyard. What was there to see but a mound of earth?

Faisal was waiting for him, holding the bridle of a cream Andalusian gelding, a steady horse, almost beyond its prime and docile, suited to the needs of an invalid who was recently and inadvisedly out of his sick bed. The Moor's dark eyes were compassionate as he handed up the reins, but he did not speak. Neither did Benedict. His heart was too full; his throat ached, his eyes stung.

They rode in silence, the cream horse smoothly pacing the miles of dusty road, worn into a rut by the tramp of pilgrim sandals. The ache in Benedict's chest eased. He blinked the moisture from his eyes, and at length turned to his silent companion.

'I did not love her,' he said with quiet intensity, 'but she was a part of me, and now it is as though that part has been cut out.'

Faisal nodded compassionately, but recognising Benedict's need to talk, said nothing. A wound had to be cleansed before it would heal.

'We were betrothed when we were children. My father could see that I was better with horses than I was with barrels of wine, so he secured me a future with the best breeder of horses in Normandy, who was also his very good friend.' Benedict grimaced at the Moor. 'The trouble was that in his enthusiasm, he betrothed me to the wrong daughter.'

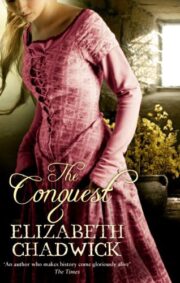

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.