The Basque sucked his teeth. 'These horses, they are expensive.' He rubbed his fingers and thumb together. 'Perhaps you do not have enough silver.'

'We shall see.'

Pons nodded. His eyes were still narrow, but the edge of anger had vanished, replaced with a glint of what might have been amusement. 'I am a merchant too,' he said. 'My whole family, they trade between our lands and yours, Frank.' He wiped the knife blade on his breeches and stabbed it into its sheath. 'I'll leave you to sleep now. Marisa and I will find somewhere else.' Bestowing a mocking flourish upon Benedict and Gisele, he disappeared into the night as silently as a cat. Like a dog, Benedict's hackles rose.

'As soon as we reach the plains, we'll hire a different guide,' he murmured to Gisele.

She clutched the reliquary at her breast, her grey eyes filled with fear. 'I don't like him,' she whispered.

Benedict made a wry face. 'And I don't trust him.'

The morning dawned bright and golden, with not a single cloud to mar the stunning blue of the sky. Shabby became quaint, primitive became rustic. The pilgrims took genuine pleasure in breaking their fast at the trestles set up in the meadow behind the hostel. Woodsmoke from the cooking fires hazed the air and carried upon it the smells of frying ham and batter cakes. There was milk and buttermilk to drink, and the air was clear and pleasantly warm.

Pons, who had not been in evidence for morning prayers, nor the main part of the meal, appeared as folk were rising from the tables. He snatched some left-over bread from a basket, speared a brown batter cake off the griddle iron on the point of his knife, and taking alternate bites from each one, set about mustering his charges.

He was in high good humour, whistling and singing as if the weather itself had entered his veins. But there was a tension about him too, like a storm building behind the sunshine.

'The road is easier today,' he announced. 'And the weather is fine. We'll make good progress.'

The pilgrims did indeed make good progress. The road was easier, but it was still narrow and stony with sharp outcrops of rock on either side. As the morning wore on, the pleasant warmth of the sun melted into a beating bronze heat. Water bottles were thirstily depleted; outer garments were removed. The Bordeaux merchant, his face the same mulberry shade as his robe, kept up an incessant litany of complaint, directed at the landscape, the weather, his fellow pilgrims, and most of all, at Pons.

The little Basque bore the merchant's tirade in silence, but his countenance steadily darkened, and he kept his fists clamped around his belt in an obvious effort to prevent himself from using them.

'I left civilisation when I left Bordeaux,' grumbled the merchant. 'If I did not love God and the blessed St James so much, I would not be here at all.'

Pons ceased walking and turned on the path to regard his charges. His dark eyes narrowed, his chest rose and fell rapidly, but it was with the effort of control, not because of the pace he had set. 'There is a wide stream beyond the next bend,' he said. 'Water the horses and fill your bottles. I'll join you in a moment.' He started to leave the path.

'Where do you think you are going?' The merchant's voice was like a whiplash.

Pons spread his hands. 'You want I should open my bowels in front of you? Do they do that in Bordeaux?' He gave the merchant a mocking stare and continued on his way, his step light and swift. Within moments he had vanished.

The merchant blustered and spluttered, his deluge of vocabulary temporarily arrested by the sheer insolence of their guide.

Benedict concealed a smile behind the pretence of wiping sweat from his face. He might not like or trust Pons, but that retort had hit the mark beautifully.

The stream was a stony mass of boulders and gravel, divided into several channels, some deep and narrow, others shallow and broad. The pilgrim company were only too pleased to dismount, water their horses and take a rest. The water was as clear and cold as glass, the pebbles on its bed shining like jewels. Gisele refilled the water skins whilst Benedict supervised their mounts, making sure that they did not drink too much.

One of the nuns daringly raised her habit above her ankles, revealing skinny white legs, and waded into the first, shallow channel. She uttered a small squeal at the coldness of the water and looked round at her sister nuns. They watched her dubiously for a moment, and then throwing caution to the wind, followed her example. The monk remained on the bank, washing his hands and face, and soaking a linen cloth to give cool respite to his sun-burned tonsure. The merchant removed his mulberry tunic, and puffing through his heavy jowls, sat down in the shade of a large rock.

He was the first to die. Silently, his windpipe severed. 'You were right about me,' Pons whispered as the merchant dumped. 'I would sooner slit your throat.'

The first Benedict knew of the attack were the two arrows that hit him, one through his side, the other through his left arm. The force spun him round and dropped him like a stone in the water. Gisele screamed and ran to him, floundering through the stream. Then she screamed again, the sound cut off before it had reached full pitch.

The water turned red and the colour eddied away down the current like scarlet fairing ribbons. Benedict was aware only of burning pain, of a weight across his body, driving that pain into every vital part of him. He tasted blood, and then the cold swirl of the water. It entered his nostrils and mouth, choking off his breath. He jerked his head up, gasping and gagging, and the pain redoubled. Gisele stared into his eyes, an expression of utter bewilderment on her face.

He tried to cry her name, but all that emerged was a wordless croak. To lift himself was agony. He pushed himself half-way to a sitting position, but the pain was too great, and he slumped back upon his wife's dead body, darkness claiming him.

CHAPTER 54

Faisal ibn Mansour, a Moorish physician in the employ of a Christian lord, Rodrigo Diaz de Bivar, had his mind on more pleasant thoughts than the stony route beneath his mule's hooves, when he and his escort came upon the scene of the massacre.

One moment, he was imagining the pleasures of home — the comfort of a couch, as opposed to the chaffing of this saddle, Maryam's quiet smile as she rubbed his feet, the laughter of their children in the room beyond — the next he was gazing at the bodies, strewn around the crossing place like so many discarded rag dolls.

'Allah be merciful!' he gasped, and drew rein so abruptly that the mule threw up its head and sat back on its haunches, almost unseating him. Kites and buzzards circled in the sky above, and as the new travellers approached the river, two black griffon-vultures took ponderous wing from the body they had been tearing apart. The birds flapped to the nearest tree and sat in the low branches, biding their time.

Faisal scrambled down from his mule and hastened to examine the bodies to see if anyone still lived. They were Christian pilgrims, he could see at a glance. Nuns and a monk, a minstrel, merchants and traders. Their clothing was sober, but of good quality. None of them wore a purse, nor was there any jewellery to be seen. There were hoofprints in the soft earth of yesterday's rain, but no sign of any horses. It was plain to Faisal that these pilgrims had been murdered by one of the bands of robbers that preyed on groups heading through the mountains towards the shrine of St James.

He shook his head in dismay as he moved from one to the other, laying his hand against their throats to check for the life-beat, holding a small mirror before their lips to see if they breathed, although in his heart of hearts, he knew that none would.

Generally, Faisal had an optimistic view of human nature. When you served such a man as Lord Rodrigo, whom the Moors knew as El Cid, you could not help but see your fellow man as worthy, but sometimes, such as now, the small, grey-bearded physician would wonder at the savagery which lurked in human nature too. Even with all his medical skills, it was not something that Faisal could cure.

Two soldiers of Faisal's escort had pulled some more bodies out of the water. A man and a woman, both of them arrow-shot. Shaking his head, tugging at his neat beard, Faisal went to inspect them. The woman had taken an arrow beneath the left shoulder blade, straight through the heart. Probably she had died even before she had hit the ground. She was slender, with a delicate, oval face and dainty features. The robbers had plundered her corpse as they had done all the others, but they had missed something. Her right fist was tightly clenched, and when Faisal gently prised it open, he discovered a small, jewelled reliquary pressed against her palm. The Christians, he knew, set much store by these objects, often reverencing them more than they did their God. He could understand that they were a focus and a comfort, but was glad that his own belief required no such props.

He shook his head over her body, and, having tugged out the arrow head, laid her flat and composed her limbs. Then he turned to the final corpse, and discovered with a sudden lurch of his stomach that the young man was still alive and watching him out of glazed, dark brown eyes.

'Bring me blankets, quickly!' Faisal commanded over his shoulder. 'This one lives, but I do not know for how long!' He knelt down in the grass beside the young man and laid his lean palm against the water-dewed neck. The pulse was steady, if somewhat slow, and was cause for reassurance. The Moor drew a sharp, curved knife from his belt.

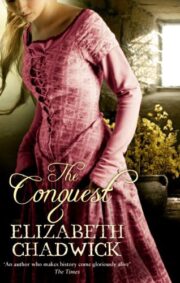

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.