Gisele looked ill too, her complexion pasty-white with puffy welts of exhaustion beneath her eyes. Julitta knew that it was not the nursing that was taking its toll, but the sight of her mother growing progressively worse, no matter how hard Gisele tried. Julitta felt genuine pity for her half-sister. She knew what it was like to lose a mother, to be powerless in the inexorable face of death.

Back at Brize, sitting with the women in the bower, Julitta listened as one of the consecration guests held forth upon the wonders of her recent pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostella in Galicia, where the remains of the blessed apostle St James were supposedly interred. The woman's name was Matilda de Vey. She was wealthy and devout, a combination of great benefit to the Church. She was also garrulous and loud, and with the aid of a couple of goblets of Aubert's fine wine was sailing very close to being outrageous. Julitta found herself longing to giggle, something that she had not done in a long, long time.

'I tell you, my dear,' she shouted at Gisele, who actually flinched, 'you have not lived unless you have been on a proper pilgrimage — not just to Rouen, but further afield. It not only does wonders for the soul, it bestows wisdom and understanding!' She plumped herself down on the bed where Arlette was resting. The entire mass sagged to the left beneath her exuberant weight. Her face reflecting the red of the wine she had so liberally consumed, Matilda pushed at her wimple which had come askew. 'On my way to visit the blessed saint, we stayed in Toulouse, at a pilgrim hospice, and there was a priest who owned a piece of the True Cross. We were all permitted to touch it.' She waggled a forefinger at her bemused audience. 'My hands were swollen up with the dropsy, but when I laid them upon that tiny piece of wood, within moments my fingers were as thin as they were on the day that I was married. I swear it to you.'

Julitta wondered why the miracle had stopped at the fingers. If Matilda had been truly blessed, then her figure would be sylph-like too. She wondered how much the woman had paid the priest for the privilege of touching the relic. Benedict had told her that he had encountered many corrupt clergymen on his journeys, who would sell anything to the gullible. 'I have seen enough nails from the True Cross to shoe an entire conroi of cavalry!' he had laughed.

'And this,' Matilda continued, delving in her ample bodice and withdrawing a small, wooden box threaded upon a leather cord, 'holds the nail clippings of the blessed St James himself!'

The other women clustered around the bed to gasp and exclaim over the dubious contents of the box. Julitta remained aloof, and busied herself replenishing the cups with wine. Am I mad, or are they? she asked herself, and grimaced to wonder whose nail clippings really occupied the little box. Why did all these saints have nails, hair, bones and clothing to spare, but never the more intimate parts? The Virgin Mary's right nipple from which the Christ child sucked? Her left one for good measure? Julitta almost choked on the thought, torn between mirth and horror at her own blasphemy. Jesu, if those biddies by the bed knew what she was thinking she would be locked up in a penitent's cell on bread and water for the next month at least!

The Lady Matilda continued to hold forth, and her audience hung on her every word. Julitta had to admit to herself that the woman possessed a story teller's skills. Her descriptions brought places and incidents to colourful life in her audience's imagination. Julitta could smell the dust of the road, feel the blaze of the sun on her spine, and taste the sweetness of the bloomy cluster of grapes that the pilgrims had eaten as they rode through the vine fields on their road to Compostella. Arlette seemed to derive pleasure from the minute details of the many churches which Matilda had visited along her route, with the various legends and saints attached to them.

'I wish that I could have seen them,' she said wistfully. 'It is too late now, my time is too short. When I was younger I wish…" Her voice trailed off and she stared into the distance and sighed heavily.

The garrulous Matilda was temporarily silenced, but quickly regained the use of her tongue, having loosened it in a long swallow from her replenished cup. 'Oh indeed, it is too late for you,' she said with a total absence of tact, 'but it is not too late for your daughter. Mayhap if you send her to pray for you, the blessed St James will grant a miracle.' She smiled at Gisele, who could only stare at her in mute shock. 'Besides,' Matilda added practically, 'she could seek out a relic to grace the new convent and bring it prestige and respect. I know places in Compostella where such things can be obtained. One of our number, a merchant from Caen, obtained a vial of the Holy Virgin's milk. Think how such a thing would glorify your convent!'

Julitta spluttered and turned the sound into a cough. The Holy Virgin's nipples suddenly did not seem so far-fetched. 'Forgive my ignorance,' she interrupted, 'but surely there are many dishonest traders in these relics. How will she know that she is not being cheated?'

Matilda stared down her nose at Julitta. 'Of course there are many dishonest traders, child. You should always ask a priest's advice before you purchase anything.'

'Oh, I see,' Julitta nodded slowly. 'Ask a priest,' she repeated.

'And use your common sense.' Matilda's eyes flashed at Julitta, daring her to speak again. 'That goes without saying, I would have thought.'

'Oh certainly.' Julitta took Matilda's advice and retreated from the confrontation. There was nothing wrong with her own common sense.

CHAPTER 52

Benedict sat at a trestle in his chamber at Brize, and counted the silver he had brought with him from Ulverton. Payment for horses by clients, the coins displayed a wide variety of mints, monarchs and petty rulers. Eric Bloodaxe, Harold Godwinson, the Confessor, the Conqueror, and even a recent William Rufus, bright as a fish scale. Benedict had deemed it prudent to remove not only himself from England, but the bulk of Ulverton's surplus coin, and if that was treason, then so be it. Rolf had entirely endorsed his decision, but his look had been wry and not a little irritated.

'You have a nose for trouble,' he had commented with a sigh and a scowl.

'Should I have yielded to him?' Benedict had retorted. 'What would you have done?'

His defence had elicited a grimace from Rolf. 'Ach, I don't know. Probably I would have promised to geld him.'

Benedict smiled at the memory and stacked another pile of silver at his right hand. Reaching to a tally stick by his left, he made a notch in it. It was not really funny. He was as good as banished from Ulverton for the immediate future. To return now would be like jumping up and down in front of an enraged bull and hoping that it would not charge.

The silver clinked gently upon the trestle, the sound comforting to his merchant blood. Raising his head he glanced across the room to his wife. She was sitting near the brazier, quietly stitching at a garment, an undershift by the looks of the fabric. Even in the privacy of their own chamber, she still wore her wimple, and the scrubbed, bleached linen did nothing to enhance her wan complexion. She was biting her lip, and as he watched her, he saw two tears trickle down her cheeks. She sniffed and reached surreptitiously into her undergown sleeve for a square of linen on which to blow her nose.

'Gisele?' He set aside the coins and rose to his feet.

She made a small sound of dismay at being discovered and shook her head, gesturing him to sit back down, but the tears came faster and harder, as if his notice had released a well-spring.

He crossed the room and set his arms around her like a cradle, and he let her cry. It had been a long time since he had held her – since he had held any woman come to that. The casual, joyous tumbles of his adolescence seemed a lifetime away, and besides, they had owned a different purpose entirely. His moments with Julitta were far too distant and far too close. And Gisele had always kept him at arm's length until she had driven him away. Now, here they were, in the same chamber, alone, with not even a maid as witness, the only disturbance the rain driving against the shutters.

Her shoulders were bony beneath his fingers; she had no more meat on her than a starved sparrow. She took too much upon herself, he thought, acting out the role that her mother had assigned to her, flavouring each moment with guilt if it was not spent in duty. He knew what she was going to say even before she calmed enough to speak.

'Mother says that she is going to take Holy vows and enter her convent at Eastertide,' she gulped. 'She has discussed it with Father Jerome and Father Hoel. She says…' sniff, sob, 'she says that it is her wish to die as a nun.' A fresh flood of weeping.

Benedict could see nothing so dreadful in that. In fact, it seemed like an excellent idea considering Arlette's preoccupation with the Church. Not only that, but if she entered the convent now, it would be the task of the nuns to nurse her, and not Gisele who was clearly drooping beneath the burden. 'What does your father say?'

'He says that it is what she wants, and that it is a wise decision.'

'And is it not?' he asked gently.

'Oh I know it is,' Gisele croaked, 'I just don't want to think of her dying. And when she enters the convent it will be like bidding farewell. She doesn't want me with her at the end.' Gisele wrung the kerchief between her fingers and laid her head upon Benedict's chest. 'I am crying for myself. I feel so frightened!'

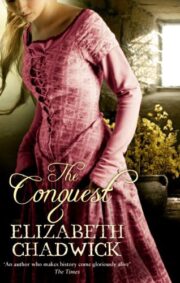

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.