'Your mother was taken sick at her convent,' Julitta said without preamble. 'I was there too, so I brought her home and promised to stay with her until you came. I was looking for Father Hoel when you arrived.'

'Father Hoel?' Gisele's face paled and she closed her fist around a silver cross and a small phial of holy water lying on her bosom. 'Is she so sick?'

Julitta shook her head. 'I do not know. All she said was that she required spiritual comfort. And of course she wants you.'

Gisele swallowed. 'I must go to her,' she said, and looked at her husband, as he came around the side of the wain. 'My mother…' she started to say.

'Yes, Doucette, I heard,' Benedict's tone was carefully neutral as he stepped aside to let her pass.

'If I had known how ill she was I would never have gone to Rouen!' Her fist still clenched on her religious jewellery, Gisele hurried towards the hall, her cloak billowing behind her. Julitta quickly turned to follow her, keeping a distance between herself and Benedict. She did not even want to feel the warmth from his body.

'Julitta, stay a moment,' he entreated.

His eyes were upon her spine; she could feel them as surely as if he had touched her. Against her better judgement she stopped, but she did not turn round. 'For what?' she asked the busy courtyard before her eyes. 'What is there to say?'

He made a wry sound. 'Too much, I don't know where to begin.'

'Then don't.' She bit her lip. 'It has taken me a long time to End my balance on this sword edge. I don't want to be cut again.'

'I'm sorry. Perhaps that should come first.'

Someone was unhitching the horses from the wain and the baggage was being unloaded. An attendant approached Benedict with a query, and he answered with distracted impatience.

Julitta briefly closed her eyes, summoning her strength. 'There is no point to this,' she said. 'I cannot bear it.' And walked briskly away from him, forcing each foot down upon the bailey floor, welcoming the sting of pain.

Benedict watched her and stamped his foot too in frustration. His first impulse was to stride after her, grab her arm and spin her round to listen to him, but he curbed it so that it was only an image of the mind. There were too many witnesses for what needed to be a personal discussion. He dug his hands through his hair in a gesture he had unconsciously picked up from Rolf, and cursed softly through his teeth. On that fateful May Eve they had both jumped into the river, had been tossed and churned in its turbulence, and finally, washed ashore on opposite banks. Now he had to build a bridge across the torrent so that at least they could have a meeting point without danger of falling in again. Perhaps it was impossible. He was fully aware that he had more than one bridge to build, not least between himself and his wife.

In Rouen, he and Gisele had knelt and prayed at the tomb of St Petronella. It was almost three years since they had wed, and in all that time, Gisele had never quickened. Of course, he admitted to himself, he had often been apart from her, and the times they did share a bed, Gisele was adamant on church strictures concerning the act of copulation. Never in Lent or on a Holy day; never in daylight. Even candlelight was shameful, and it was better to remain clothed. If he forced her to go against these rules, she became tearful, and would go remorsefully to confession, imploring him to do the same for the sake of his mortal soul.

Her mother's recent ill health had changed matters somewhat. Arlette had wistfully hinted about holding her first grandchild in her arms. Prayers had been said, and Gisele had taken to drinking potions of betony and figwort in the belief that these would help her to quicken. And although not particularly enthusiastic, she had made herself a more willing bedmate. Without success as yet, hence the visit to St Petronella.

Benedict left the attendants to finish unloading the wain and went to the hall. A rapid glance around the main room revealed no sign of Julitta. The household was dining on an evening meal of meat stew and flat loaves. The seats at the high table were occupied by several of the Brize knights and their families, but the heavy carved chairs at the head of the board were empty. He could have sat there and presided over the meal, but he owned neither the desire nor the appetite.

Leaving the hall, he climbed the outer stairs to the rooms above. Julitta was not here either. He walked past the loom, the polished bench, the precisely placed coffer on which stood a small basket containing hair ribbons and fillets, and a carved antler comb. He pushed aside the curtain which partitioned off the bedchamber, and entered its private sanctum.

Arlette was propped upon a mountain of pillows. Against the linen of her chemise, her face was positively yellow, and the bones of her face were gaunt. Benedict was shocked by her appearance. He knew that her health had been poor, but it had always seemed suspicious to him that it deteriorated whenever Gisele had to give her attention elsewhere. Now he could see her mortality written in her eyes.

Gisele sat on the bed, holding her mother's hand and talking quietly, but she ceased when Benedict entered and glanced at him with worried eyes. To one side, her maid was making up a truckle bed with clean linens and sorting Gisele's bedrobe from the travelling coffer that had been lugged up the stairs from the bailey. Benedict eyed these signs with depressed resignation. So much for St Petronella.

Advancing to the bed, he leaned over and kissed Arlette on her hot, dry cheek. 'Mother,' he acknowledged dutifully and resisted the urge to wipe his mouth on the back of his hand.

'Son.' Arlette's own response was tepid.

Benedict knew the rules of the women's domain. It was his duty to pay his respects and then depart. The only men who had access to the bower and bedchamber were those of the family — Rolf, himself, and Mauger at the limit. Arlette had always made it clear that he was tolerated rather than welcomed.

'I am sorry to hear that you are unwell.'

Arlette shrugged. 'It will pass,' she said wearily. 'It always has before.'

'You need sleep, Mama, and plenty of rest with someone to look after you.' Gisele patted the hand beneath her own. 'I am here now, and I promise not to leave your side until you're better.'

'You're a good child.' Arlette's gaunt face brightened slightly. Then she looked at Benedict. 'I asked Julitta to bring Father Hoel to me, but I think she must have forgotten. Will you go and see if you can find him?'

Benedict complied with alacrity, as glad to leave the room as Arlette was to see him go. On the outer staircase he inhaled deeply of the crisp September air, cleansing his lungs. A full, silver moon was rising, in a clear, star-bright night sky, beautiful and cold.

At the foot of the stairs, he encountered Father Hoel on his way up. Obviously Julitta had not forgotten. When he enquired as to her whereabouts, the elderly priest spread his hands.

'I do not know. I only met her in passing in the bailey. You could ask the guards.'

'Thank you, I will.'

Within the keep torches, candles and rush dips shed their light and shadow over plastered walls, embroideries and hangings. Hazy ribbons of blue smoke layered the hall and meandered without any great haste towards the vent holes.

Viewed from the wooden stairway connecting the upper and lower sections of the castle, the river Risle possessed the black sparkle of a jet necklace and the surrounding land was an ocean of soft, dark-blue hummocks. He heard the snort of a dozing horse, and the intermittent creaking of a storeshed door.

The guards on duty near the gates in the lower bailey were warming themselves at a brazier filled with firewood. One of the wives had brought out a covered iron container of pottage for their supper, and her husband was setting it to keep warm. Benedict's query was met with shaken heads and frowns. No, she had not left the keep. Yes, she had been in the bailey talking to the priest, but they hadn't taken much notice of where she went after that.

Benedict did not want to make too much of an issue of his search and arouse unwelcome curiosity. 'If you see her, tell her that I will be in the solar or the hall,' he said casually, and turned away.

A child belonging to the soldier's wife had wandered across his path and he almost tripped over the infant. Its face and hands were shiny and sticky from the piece of honeycomb it had been sucking with total absorption. A glistening smear dripped down the expensive blue wool of Benedict's tunic. Mortified, the mother grappled her offspring away, apologising profusely.

Her words fell upon deaf ears. 'Of course, the bees,' Benedict said with a gleam of comprehension, and to the bewilderment of the gathering around the brazier, set off in the direction of Arlette's garden. It was built against the outer wall, a haven of retreat, a pleasant suntrap, where Arlette and Gisele came in fine weather to sew and listen to moral fables and readings from the scriptures. The garden was surrounded on three sides by walls, with a gated entrance to prevent animals from wandering in and destroying the plants, of which Arlette was inordinately proud.

The moonlight cast a luminous, silverish light over trees and shrubs, herbs and flowers. Scents assaulted him, sweet, bitter, astringent, muskily soft. Drugged moths floated from flower to flower, and above his head he heard the shrill squeaks of hunting bats. He followed the path to the well which was the garden's focal point. The gardener had left a hoe leaning against its side, and a wooden dibbing stick, the soil dark on its tip. Benedict continued along the path until he came to the corner against the outer wall, his footfalls and breathing cat-light.

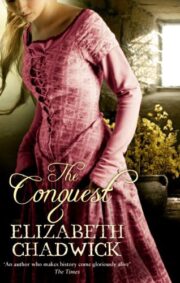

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.