Julitta flickered a brief glance around the bailey. It was all so strange, and yet so familiar. She was tired from a journey that had been as much emotional as physical, and was far from over. She did not remember her father's wife from their chance encounter eight years ago, and the woman was nothing as she had imagined. Arlette de Brize was composed, attractive, and immaculately groomed, the sort of person who could walk along a muddy track without so much as smirching her dainty shoes. Julitta was aware that her own appearance, although much improved since London by new clothes, fell far short of the older woman's approval. But then, she thought mutinously, she had no need of that. She raised her head, and unconsciously tightened her jaw.

Arlette turned to the demure young woman standing at her side. 'Gisele, greet your sister,' she commanded.

The girl hesitated, then stepped forward with obvious reluctance. 'Be welcome,' she said in a monotone and kissed the air beside Julitta's cheek.

Julitta inhaled the astringent scent of lavender. This was Gisele, Benedict's betrothed. She was filled with the hazy memory of herself in a rage of infantile disbelief that her father should have destroyed her dreams and betrothed him elsewhere — to her own sister.

'Benedict told us all about you,' Gisele said sweetly, displaying that she possessed claws, no matter how dainty the paws that sheathed them, 'that he rescued you from a bathhouse.'

Red heat flooded Julitta's face.

'Actually it was from a grouchy Thames boatman,' Benedict interrupted easily from his place among the escorting soldiers and grooms. 'They think they own the world.'

Julitta gave him a grateful look, Gisele a narrow one.

'Come.' Arlette took Julitta by the arm as if she were taking the lead of a recalcitrant puppy. 'Let us go within. You will want to wash away the dust of travel and rest before we eat in the hall. Gisele, see to everyone's comfort and then join us.'

'Yes, Mama.' Gisele's voice was a dutiful chime, sweet and slightly high-pitched. Julitta imagined that given the chance it could be shrill and whiny. She longed to remove her arm from beneath Arlette's and gave an experimental tug. The slim white fingers tightened and the grey eyes silently warned her to do no such thing. Julitta yielded, but if anything, the spark of defiance kindled by Arlette's reception, was only fanned to a flame.

'I can see that Felice de Remy has done her best for you, but you need taking in hand,' said Arlette. They had retired to the privacy of the chamber above the hall. It was divided by a wattle and daub partition into two rooms, one being the main bedchamber, the other Arlette's working domain. The orderliness of her character was reflected in the precise arrangement of every item of furniture. The upright loom was placed just so to gain light from the window aperture. A dark oak bench leaned against the wall, its positioning exactly central. Julitta wondered if Arlette had used a measuring stick. Everything was neat, dust-free and firmly put in its place. More to be admired than used, Julitta thought.

Arlette walked round Julitta, examining her as if she were a doubtful piece of ware that she had been duped into buying by a travelling pedlar. Her fingers plucked at the sage-green linen of Julitta's over-dress which had been completed in a rush on the night before she set out from London. Some of the stitches, mostly her own, were over-large, and Arlette clucked her tongue over these.

'Sewing and weaving, baking and brewing,' she declared like a devotional plainchant. 'I do not suppose that your mother had much opportunity to teach you any of those. Well, you'll soon learn. You have your father's looks, so I suppose you must have his quick wits too. If you are to be of any profit to Brize when your marriage is arranged, it is my duty to make a silk purse from a sow's ear… and it is your duty to learn.'

Julitta's eyes flew wide at the words profit, marriage and duty. She knew it was the lot with which most women were burdened, but she had lived outside its conventions for most of her life and was filled with horror at the thought of conforming. 'My father did not bring me to Ulverton to be groomed for sale like one of his mares,' she said with a toss of her head.

Gisele looked primly horrified at Julitta's rebellion. Arlette's stare was cold. 'Your father at least acknowledges his duty,' she said icily. 'He could have left you in the gutter. Think about that, my girl, before you open your mouth to be ungrateful. I'll not have you shaming the proud name of Brize-sur-Risle.'

Julitta blinked hard, fighting tears. She would not cry in front of her half-sister and her father's wife. At the moment she hated both of them, and she knew without a doubt that they hated her. 'What makes you think I would rather not live in the gutter?' she said hotly.

Arlette's thin eyebrows rose to meet her wimple. Her face wore an expression of fastidious distaste. 'Certainly your manners smack of such habitation,' she replied, and terminated the exchange by returning to practical details. 'You will sleep in here with Gisele and the maids. You did not bring many belongings from London, but what you possess, you may store in that coffer.' She indicated an oak chest standing next to a neatly arranged stack of mattresses. 'Tomorrow we shall see how much you know and what you can do.'

Julitta opened her mouth to rebel again, but thought the better of it. Whatever she said would only fetch a rebuke. She had to use guile. Arlette and Gisele had already formed their opinions as to her character and worth, but there were others she could win to her cause, chief among them her father. So instead, she composed her expression meekly and lowered her eyes as if she had been cowed into submission.

Watching over Julitta as she put her few belongings in the coffer, Arlette uttered a horrified squawk when she saw the size of the honed dagger that the girl laid across the top of her spare gown and short shift.

'Surely that is not your eating knife?'

Obviously it was not, for Julitta's small, bone-handled meat-blade was hanging in the leather scabbard at her belt. 'It was my mother's,' she said.

'Your mother wore a murderous thing like that?' Arlette's voice remained horror-struck.

'Sometimes.' A devil in her prompted Julitta to lay her hand to the hilt of polished antler and slowly draw the blade forth from its sheath. 'She always kept it sharp. See, I have her whetstone too.' In her other hand she held up a stone suspended from a small belt cord. 'I know how to hone the edge,' she said confidently and ran her thumb along the blade, 'but it doesn't need it just now.' She gave Arlette a feline smile.

'Put that thing away!' Arlette said hoarsely, one hand at her throat as if she expected to be assaulted. 'It is no fit possession for a girl of your breeding to own. I shall speak to your father about this!'

Julitta shrugged. 'He knows I have it. He saw it in London and he let me keep it. It was made by Mama's husband. He was a master armourer in the days before King William.' She sheathed the dagger and replaced it in the coffer. 'We got rid of the battle axe though.'

Arlette's eyes almost popped out of her head and she did not ask to have the last statement explained. 'Your father is frequently too soft for his own good,' she snapped. 'Keep that thing from my sight. I hate to see weapons in my bower.' A small shudder of genuine aversion ran through her.

Julitta wrapped her shift around the weapon. There were chinks in the armour if you knew where to probe. With satisfaction, she knew that, if necessary, she could give as good as she got.

Being the implicit believer in duty that she was, Arlette had prepared a feast to welcome Julitta into the household. Sitting on the high dais, surrounded by embroidered napery, glazed earthenware vessels, an elaborate aquamanile and matching silver salt dish, it was difficult for Julitta not to feel intimidated. At the bathhouse she had eaten off a plain trencher of wood or stale bread, and the food had been simple — pottage more often than not, or a split loaf served with butter and curd cheese. At the de Remys' she had grown accustomed to dining in a little more style, with a cloth on the trestle for the main meal, and a wider choice of dishes, but this was overwhelming.

She looked at a platter of roasted songbirds that had been placed close to her right hand. They were something she had never liked. Their tiny size always filled her with feelings of grief for their death. She could not bear the feel of their frail bones in her fingers. To her left a shoal of trout adorned a flat wooden dish, overlapped one upon the other, their skins brown-silver in the candlelight, their boiled eyes milky-white.

'Are you not hungry?' her father asked with concern.

Julitta shook her head. Her stomach was empty, but the fare set before her had killed her appetite, as had the formality. She would far rather have sat among the servants in the main body of the hall and shared their soup and stewed meat.

Rolf eyed her thoughtfully. 'It is too much, isn't it?' he murmured quietly, so that Arlette's sharp ears should not hear.

'My mother never gave me food like this,' Julitta said. She knew that she was being petulant and ungrateful, but it had come to her as she sat down to the feast, that in the old days her mother would have sat in Lady Arlette's place. Although Julitta's memory of those times was hazy, she did know that the meal would have been edible and the atmosphere warm and informal.

'Oh, but she did,' Rolf said with a wry smile, 'but never presented in quite the same way. This is how we would eat at court. You are done a great honour. You like fish, don't you?' He deftly removed one of the trout from the serving platter, set it down on a spare trencher, and with a few practised motions of his eating knife, removed the head and filleted the body, turning it over to expose the moist pink flesh. Then he transferred it to her trencher. 'I can promise you it tastes good.'

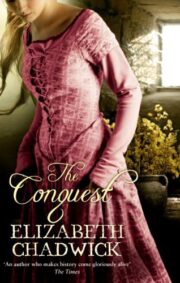

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.