'All right, let her go,' he commanded, and retreated, his arm slick with bloody grease and birth fluid.

Free of restraint, the mare folded onto her side and within moments had pushed out the foal's forelegs and head. Rolf dropped to his knees and helped her deliver the rest of her baby. Working quickly, he stripped the birth membrane from the foal's face and body, and cleaned out its mouth and nostrils so that it could breathe.

'A colt,' he announced with pleasure to Tancred and the groom.

'There's no mistaking old Orage's blood,' Tancred grinned, as relieved and delighted as his lord. 'Look, he's even got the same star marking between his eyes.'

Orage, the foal's sire, was Rolf's prize stud, a striking golden-chestnut stallion of stamina, mettle and intelligence. Almost every foal born to his siring was chestnut, and this trait had become an identifying mark of the stud at Brize-sur-Risle.

Already, despite the difficult birth, the foal was struggling to coordinate his spindly legs and rise. His mother swung her head towards him and uttered a low, encouraging nicker. Rolf gathered the damp baby in his arms and placed him under the mare. She snuffled at her foal, drinking in his scent, and then began to lick him vigorously with a muscular pink tongue.

Rolf swilled his arm, donned his shirt and tunic, and stayed to watch the foal take his first drink from the mare's dripping udders. Satisfied that all was well, he left mother and son to Tancred, and returned to the keep.

At the top of the wooden stairs bridging the slope between the castle mound and the lower courtyard, he paused to watch the dawn break over the lands of Brize-sur-Risle. Veiled in sleety rain, they yielded a vista of dull greenery to his eyes. He could see the thatched roofs of the village and the grey stone curves of the church where his father was entombed. Full of sluggish power, the iron ribbon of the river Risle flowed away from him towards the port of Honfleur. Staring at the water, he felt a sudden stab of poignant longing that possessed neither rhyme nor reason. This was his home, his inheritance. Why was it not enough? Or perhaps the pull of the river was stronger than the pull of the land to the fierce Viking blood in his veins. The icy air was cauterising his lungs. He stared for a moment longer, then, shaking his head like a man shaking off a dream, went inside his keep.

Berthe, the wet nurse, was suckling his infant daughter before the fire in the great hall. As Rolf came to warm himself, the woman lifted the baby off her breast, shrugged up one shoulder of her gown, and yanked down the other side. Rolf stared, mesmerised by the enormous blue-veined globe, the wide areola and fat brown nipple. His daughter bobbed her head frantically from side to side, found what she sought, and attached herself with a single, voracious gulp.

Berthe looked up at Rolf with sly, knowing eyes. He remembered her heaving, hot body beneath his in the straw, her enormous breasts slippery with leaked milk and sweat, the tight sucking of her lower mouth. His loins coagulated and his stomach jerked. It was too early in the morning to be contemplating such images.

Avoiding her avid gaze, he prowled to his chair at the high table and directed a servant to bring him bread and wine to break his fast. His steward approached with a query, and then the priest, Father Hoel, wanted to ask a favour. Rolf dealt summarily with both, impatience crawling through his bones. The servant returned with a dish of hot, new bread, a crock of honey, and a jug of watered red wine.

'How's the mare?'

Rolf sucked honey off his thumb and glanced at his wife as she took her place beside him. She was as pale as a moth, as elegant and insipid. Two long, thin braids of silver-brown hair fell over her flat bosom to her narrow hips. Her face was smooth, her features pretty, falling just short of beauty. Her eyes were a striking clear grey with a darker, smoky rim between iris and white.

'Well enough. The foal's forelegs were stuck, but once they were free, she delivered without a problem — a fine colt; should fetch a good price if I decide to sell him.'

She broke a morsel from the loaf in front of Rolf and nibbled at it. 'You might keep him, you mean?'

'One day I will need to replace Orage. I have to look at every colt born and assess whether this is the one.' He watched her toy with the food. Their suckling daughter was almost five months old now, but it had taken Arlette all that time to recover from the birth. She never carried well. Before Gisele, there had been three miscarriages and one stillbirth. In Rolf's opinion, she did not take enough care of herself, scarcely eating enough to sustain a sparrow. Small wonder that she had been unable to feed the infant and they had had to employ a wet nurse. He often entertained the disloyal thought that if she were a brood mare, he would have disposed of her long since despite her illustrious bloodline. But she was a superb chatelaine, possessed of formidable domestic skills. Tidiness and industry were the codes by which Arlette ruled her world. The hall was well ordered, food was never burned or undercooked; his clothes were kept clean and in a good state of repair. If she had been more fruitful and of a less prim nature, he would have had no complaints. As it was, he tolerated his lot, but without any gut-sparking surges of love or joy.

Arlette continued to nibble at her crust, moistening her mouth with dainty little sips of wine. It was like sitting next to a mouse, Rolf thought with irritation. Deliberately wolfing his own food, he pushed himself to his feet.

Arlette gazed up at him, her grey eyes wide and startled. 'Where are you going?'

'To look over the yearlings. William FitzOsbern asked me to search out some likely ones for training up.'

'In this weather?'

'It is better than being cooped up in here.' Brushing perfunctorily at the crumbs on his tunic, which was already stained from the stable, he left the hall.

Berthe had tucked her breast back inside her gown and was winding the baby. Her eyes followed Rolf hungrily. So did Arlette's.

Free of the smoky atmosphere and the constraints of the hall, Rolf breathed a sigh of relief and went to check upon the mare and foal again. The colt had folded up in the straw to sleep, his small belly as tight as a drum. The mare dozed on one hip, standing protectively over him. Smiling, Rolf left them and ordered a groom to saddle up the old black gelding he used when working among his herds.

While he was waiting, he heard a commotion down at the bailey gates, and emerging from the stables to look, saw the riders entering the yard two by two, liquid mud spraying from the shod hooves. The leading man carried a brilliant yellow and black gonfalon, the ragged edges snapping out in the vicious, sleety wind. Behind him, astride a prancing chestnut stallion, came William FitzOsbern, one of his regular customers. He was a close relative and trusted advisor of Duke William's, and very powerful. With this borne in mind, Rolf put a smile on his face and went to greet him.

FitzOsbern grimaced as his horse was led away to a warm stall. He stamped his feet briskly on the ground to restore feeling and beat his hands upon his thick woollen cloak. He was between forty and fifty years old with fine spider lines creasing the gaze of shrewd hazel eyes and deepening into seams between nostrils and thin-lipped mouth.

'Hirondelle looks fit,' Rolf said, as with resignation he retraced his steps towards the confines of the hall. He doubted that William FitzOsbern would appreciate viewing any stock until he had been warmed by fire and wine.

'Full of himself,' said FitzOsbern expressionlessly. 'Tried to buck me off twice this morning. If I had known how frisky he was going to be, I'd have thought twice about buying him off you.'

Rolf glanced sidelong and saw the glint of amusement in FitzOsbern's eyes. When Rolf had first started dealing with him two years ago, he had found FitzOsbern's expressionless delivery extremely disconcerting. Was the man speaking in earnest or in jest? Rolf had since learned to read the signs, but they were hardly obvious – a slight turn of the lips, a deepening of the eye creases, if you were fortunate.

'You'll thank me for the fire in his feet when you take him on a battlefield,' Rolf retorted.

'Interesting you should say that.' FitzOsbern preceded Rolf into the hall and looked around with the keen eye of a connoisseur. His gaze lit on Arlette, who was supervising the clearing away of the breakfast repast, her hands busy with a drop spindle and fluff of carded fleece.

Noticing the men, she hurried over, her pale complexion suffusing with pink.

'My lord, what a pleasure,' she said to FitzOsbern.

Rolf could tell that she meant entirely the opposite. He could see her mind flurrying to the kitchens to check if they had enough food, could see her wondering where they were going to accommodate FitzOsbern and his entourage if he decided to stay the night. She would manage, she always did, but not without a deal of anguish and hand-wringing in private.

'The pleasure is mine,' FitzOsbern returned as a matter of Form, inclining his head.

'Bring us hot wine to the solar,' Rolf said, then added to FitzOsbern, 'Will you stay to eat with us?'

'Thank you, but no. I have to press on to Rouen, and if this sleet becomes snow, the roads will be difficult.'

Rolf could almost hear Arlette's sigh of relief as she hurried away to mull a pitcher of wine. He took their guest to the long room on the floor above the hall. It had been divided up into living and sleeping quarters by the artful use of woollen curtains and embroideries. Near the window a woman was busy weaving at a tall loom. Rolf dismissed her and directed FitzOsbern to a cushioned box chair positioned close to a glowing brazier. He fetched himself the stool on which the maid had been sitting.

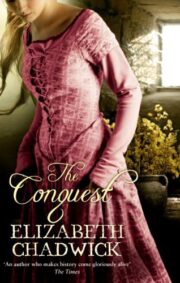

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.