'So that is why you are going north — because you cannot scratch your itch?'

Rolf pursed his lips to consider. 'No,' he said after a moment. 'Whether I had bedded her or not, I would still take the road to Durham.'

Aubert grunted. 'Then you are not as much in thrall as your body thinks.'

'And there are bound to be willing women along the way,' Rolf added with a self-mocking grin. He rose and stretched, his glance meeting Ailith's across the room. Benedict in her arms, she smiled and hastened over to him.

'Have you spent all my money?' he teased.

'Do not judge me by your own standards,' she retorted smartly. 'I have brought you home a full bag of silver.'

'Hah, then what did you buy?'

'Linen for shirts and shifts, needles and threads and herbs. A loaf of sugar.' She ticked off the items on her fingers while Benedict rested in the crook of her arm and grinned at Rolf as if he was party to a great jest. 'Some pottery cups for the high table. They stack one inside the other, according to size, so they'll be easier to store than the ones we've already got. I bought myself a new belt since my old one is almost worn through, and two dozen weaving tablets. Oh, and this.' She gave him Benedict to hold and delved into the pouch at her waist. 'For you,' she said, reddening a little as she presented him with a silver cloak brooch in the shape of a six-legged horse.

'It is bought with my own coin from the sale of Goldwin's forge. It is to thank you for all you have done for me, and to bring you good fortune. I know you set score by your talismans.'

Rolf looked at the token in his palm – Sleipnir, the legendary mount of Odin the all-father. He was touched and proud. He also felt more than a little unworthy. Stooping slightly, he kissed her cold cheek. 'It is more than I deserve,' he said.

Felice joined them, taking Benedict from Rolf's arms. 'Is it not pretty?' she asked, nodding at the brooch. 'The moment Ailith set eyes on it, she was determined to buy it for you.'

Pretty was not the word Rolf would have used to describe the stark, spartan lines of the clasp, but he nodded all the same.

'While we were discussing the price with the silversmith, we saw Wulfstan and his new wife,' Felice added.

'His new wife?' Rolf looked up in surprise. He touched his throat, remembering Wulfstan's fist squeezing there and the spittle of rage on the Saxon's beard. 'He recovered from his disappointment soon enough.'

'The damage was to his pride, not his heart,' Felice said darkly and wagged a salutary forefinger. 'Do not think he has forgiven and forgotten? He hasn't spoken to us since you took Ailith to Ulverton.'

'Small loss,' Aubert grunted from his seat by the fire.

'And you say he's married now?' Rolf asked.

'In the autumn to the daughter of another goldsmith. Wulfstan must have got her with child on their wedding night because she is showing as round as a barrel and he is at pains that everyone should see the results of his prowess.'

Rolf pinched his upper lip between forefinger and thumb. 'Did he speak to you?'

'He didn't see us,' Ailith said quickly. 'We hid our faces until he had passed. I felt sorry for his poor wife. She was dressed in so much finery that it was weighing her down, and I could tell that she was longing to be sick. When I think that it could have been me…" A little shiver ran through her.

'But it isn't,' Rolf soothed. 'You are safe forever from such as he.'

Aubert spoke up, trying to dispel the sombre atmosphere that had suddenly settled, 'Out of the frying pan and into the fire, I would say.'

Ailith reddened and excused herself to the safe stowing of her purchases. She heard Rolf say something reproachful to Aubert, although she did not catch the words, and then Aubert's hearty laugh, which terminated in a bout of coughing.

Moments later, Rolf joined her in the corner of the hall where her pallet and belongings lay. 'I'm going north for a few months,' he announced.

'North?' Ailith stopped what she was doing and stared at him. 'Where?'

'To Durham with Robert de Comminges. He's been appointed earl in Gospatric's place. I have heard that there are good sumpter ponies to be bought in Mercia and Northumbria.'

She was gripped by a cold feeling of dismay, 'The north has not been tamed. My brothers used to say that the peoples beyond the Humber saw King Harold as a foreigner. They look to the Norse for their succour. Their language and their ways are different.'

'I know,' he said without concern. 'My own family were once Vikings. I am told that my great-grandfather was as fluent in Norse as he was in French.'

She shook her head. 'You will be putting yourself in great danger.'

'No more than I ever did by joining the English expedition in the first place.'

Her lips tightened. She turned away and began folding the yards of bought linen into a coffer. 'You have responsibilities that you take as lightly as your care for your own life,' she said without looking round.

Rolf snorted. 'I know my responsibilities. Christ, you sound like my wife!'

'Then follow your whim up the great north road,' she retorted stiffly, 'and pray that your gains outweigh your losses.'

'What is that supposed to mean?' He grasped her arm and dragged her round to face him.

Ailith shook him off. 'You fool. Do you never stop to think that the green on the other side of the hill might be nothing but a quagmire?' She glared at him, banged down the coffer lid, and stalked away.

Rolf had not bargained for such a hostile response. Several emotions assaulted him at once. He was angry at the manner in which she had spoken to him, and that in turn made him all the more determined to travel north. He had wanted to take her in his arms and brutally cover that furious mouth with a kiss. Lust, frustration, the need to possess. Most unsettling of all, as he stood staring at the coffer and the empty pallet, a treacherous thread of reason told him that he should heed her opinion and bide here in the south.

A sharp pain in his clenched fist caused him to look down and see that the pin on the silver cloak clasp had come unfastened and stabbed his palm.

CHAPTER 24

North of York, two days' ride from Durham, Rolf took his leave of the Norman army and its arrogant commander Robert de Comminges. Partly this was because Rolf desired to investigate the types of horses and ponies that these northern climes bred, but the other part of the decision was caused by Rolf's irritation at the attitude of his fellow Normans.

They treated the lands through which they rode as conquered territory, not asking, but taking what they wanted with a rough hand. Any who made complaint or resisted found themselves looking down the blood gutter of a war sword. In their wake, de Comminges' army of mercenaries left a smouldering resentment, and the further north they rode, the brighter grew the embers and the less cowed became the people. Here, the majority of the local lords were still of the native Anglo—Danish blood. They owed their allegiance to the English earls Edwin and Morcar, and to Waltheof, son of the great Siward of Northumbria. These powerful English lords might have bent the knee to William of Normandy, but what they really wanted to do was spit in his face.

'We have to show them with an iron fist that we are the masters,' Comminges said to Rolf. 'If they think for one moment that we are weak, they will be upon us like a pack of wolves.'

Rolf grunted and tightened the cinch on his chestnut's girth. Dawn had broken a hole in the slate-coloured sky, and a half moon was lingering to greet it. 'I have no doubt you are right,' he replied, thinking of the dark scowls they had received along their way.

'You should not be leaving us to ride alone.' Rolf raised his brows at de Comminges. The man had a florid complexion that was threaded with a hard drinker's broken veins. The upright stubble on his scalp, short-shaven at the back, gave him the look of a man who spent all his time in fights, most of them disreputable. But Robert de Comminges, for all his brutality and arrogance, was no mindless vandal. He had a brain when he chose to use it. 'You have your horses,' Rolf said to him, 'and I have my money. I doubt that Durham will be any safer than the villages round these parts.'

'Yes, but there are more of us.'

'And a greater native population in Durham,' Rolf pointed out. 'Do not worry about me. I can take care of myself.'

De Comminges looked sceptical. 'There are bound to be refugees from Hastings up here.' He scowled. 'You'll be dead before you're even out of the saddle.'

'The sword is a language that every man understands,' Rolf answered. 'But so is trade. Wherever one goes, so does the other.' Catching up the reins, he swung across the chestnut's back. 'I will see you in Durham town, within a seven day.'

De Comminges snorted. 'I'd wager on that boast if I ever thought I'd see the colour of your coin.'

'How much?'

De Comminges pursed his thin lips and rubbed the back of his shaven neck. 'The price of a good warhorse.'

'Agreed.' Rolf reached down from the saddle to seal their bargain with a handclasp. De Comminges had a meaty palm and solid, fleshy fingers. Even now, in the chill dank of a winter dawn, they were moist and slightly warm.

Rolf's were cold. As he rode out of the Norman camp, he pulled on his sheepskin mittens. They were proof that, despite the difficulties, trade was possible with the natives of northern England. He had bargained for the mittens in York with a shepherd's wife. While she had made her contempt of all Normans obvious, she had not scorned his silver. It was in York too that he had learned of a horse-trader who might be willing to deal with him.

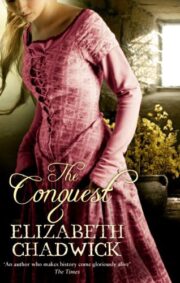

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.