Ailith nodded. 'Of course,' she said, her lips tightening. Rolf looked thoughtfully between the two women but made no comment, and when Felice linked her free arm through his to lead him back into the house, he smiled and yielded her his full attention.

The hearth smouldered softly, bathing the woman and baby in a dull red light. Awake, Rolf lay on his pallet and watched Ailith suckle Benedict in the hour when everyone else was sound asleep. Her hair was braided in a loose sheaf and secured by a simple ribbon. She had freed the baby's limbs and a little hand clutched her plait as the infant sucked. Rolf quietly enjoyed the scene. He had never witnessed Ailith off her guard before and the softness in her face as she played with Benedict was a revelation. He had not had much opportunity to speak to her since his arrival. At first she had been busy with the maids preparing food, and when she had sat at table, the conversation had all been in rapid Norman French and she had been unable to follow it and join in — or perhaps she had not wanted to. He had seen a look of strain on her face as the evening wore its way down the candle notches.

There was no strain now. She finished feeding the baby and covered her breasts. Quietly he left his pallet and crouched down at her side before the banked fire. He felt her silent surprise, but she accepted his company.

'How are you faring?' he enquired as she set about changing Benedict's swaddling. Her fair braid swung forward. The movement of her breasts was heavy and fluid within her chemise. After one, rapid glance, he kept his eyes on her face, but she did not look at him, preferring to busy herself with the baby.

'Well enough. I still miss Goldwin and Harold terribly. It is an ache that will never go away.'

'But you are no longer tempted to take a knife to your wrist?' His voice emerged sharper than he had intended.

'I am tempted every day, but I manage to resist,' she answered.

He eyed her thoughtfully. While the child needed her for sustenance, he could see that she was sufficiently fulfilled to think life worth living. But what about the future? He had seen the unspoken tension between her and Felice and how it stemmed from mutual jealousy over Benedict. Sooner, rather than later, he thought, the battle to wean the baby would begin.

Having saved her life in the forge at midwinter, Rolf felt that he had a responsibility for Ailith's welfare, one that he would rather have foregone. In the normal course of his life, he would have tumbled her joyously in the warm stable straw without a second thought and then gone on his light-hearted way. And if she refused him, which occasionally happened, he would have shrugged and found someone else to lighten the heaviness in his groin. Now, burdened, he was at a loss.

'How long will you be gone in Normandy?' She returned Benedict to his cherry wood cradle and set it gently rocking with her toe.

'For the spring and early summer. I have to look over the new foals at Brize and decide what is to be done with the yearlings. I'm going to bring some horses back to England with me as breeding stock for Ulverton. It was the reason the King granted me the lands – to raise warhorses for his stables. I may go to Flanders too. They raise heavier animals there, ideal for blending with my Spanish grey. Breeding the perfect warhorse is not easily done, but I have always relished a challenge, and I suffer from the wanderlust,' he added with a smile.

'Is that what brought you to England? Your wanderlust? The challenge of another man's grass?'

Rolf shrugged uncomfortably beneath her stare, which was almost accusing. 'In part, yes,' he confessed, 'but King William had need of my skills and no-one ever denies his will — not if they want to live.'

'And did you leave a family at home in Normandy when you crossed the narrow sea?'

Rolf sighed down his nose. He had known the question was inevitable, and would have preferred not to answer her. Normandy was Normandy, and England was England. 'I have a wife and child,' he said.

Ailith's expression became closed and wary as he had known it would. 'It must be hard for you, being apart from them for so long,' she murmured.

'Sometimes it is.' He picked up a twig of stray kindling from the floor rushes and peeled at the bark with his fingernail. 'I was married to further the interests of Brize-sur-Risle – for wealth and land and politics. My father was the most astute of men when it came to such dealings. I had no choice. Not that it mattered. Arlette was suitable in every way and there was no-one else.' He poked the twig beneath the smouldering logs in the hearth. 'She is a good wife,' he said, his tone wry. 'Near to being perfect.'

The kindling smoked at the tip and turned black. The bark writhed away from the pith and suddenly bright flame licked intensely along the twig and consumed it. Rolf stared at the blackened, crumbling fretwork. 'Perhaps that is why I have a need to play with fire,' he said softly.

CHAPTER 18

Rolf fondled the bay mare's soft muzzle. A leggy red-gold yearling butted jealously at his hand, seeking attention, and the mare's new chestnut foal stretched his neck to discover if he was missing anything. The dark January night of a year and a half ago when Rolf had struggled to save the yearling's life seemed to be from a different lifetime, so much had happened since.

'England,' said Arlette. 'You are taking them to England?' There was anxiety in her voice. 'But she is your best mare, Rolf.'

'I want to breed her to Sleipnir,' he answered. 'And there is no way on God's good earth that I am bringing him back across the narrow sea. Once was enough. She has mated well with Orage, I won't deny it, but I want to see the result of putting her to the grey. There are some other mares I have a mind to take too.'

Her eyes clouded. 'That means you will be spending much of your time in England.'

'For a while, until the lands are more settled, and the breeding established.' He ceased stroking the mare and sat down on the river bank where Arlette had organised a picnic. In the village he knew that his people would be dancing around the maypole and indulging in various pagan rites connected with the celebration of the fertility of spring. Father Hoel would be among them, scattering blessings and holy water in a vain attempt to Christianise the proceedings. Rolf would have preferred to join the dancing and oversee the feast he had provided for his people, but Arlette, full of righteous disapproval, had suggested the alternative of dining by the river in the sunshine, adding that in the month he had been home, they had scarcely been together except at retiring time.

He had complied, for it gave him the opportunity to inspect his horses, nor was he averse to a lazy hour beside the peace of the river. Besides, the May celebrations would go on all day, and well into the night. And the night was usually the best part.

Watched closely by her mother, Gisele toddled about on the grass, constantly plumping down on her fat little bottom. Delicate pale gold curls escaped the edges of her linen bonnet and framed a dainty face that was Arlette's in immature miniature. Rolf took her on his lap, but she struggled free immediately.

'Want Mama,' she whined, and tottered over to Arlette. Shrugging, Rolf dug a stone out of the ground and threw it at the water. It vanished with a plop, leaving only the ripples radiating downstream. Arlette directed a squire to pour him wine from the stone bottle that had been cooling in the shallows.

'Perhaps I could go with you to England,' she suggested tentatively as she settled Gisele on her own knee.

'No!' Rolf snarled, surprising himself as much as his wife with the vehemence of his denial. He realised, as her great, grey eyes rested on him in shock, that he did not want her bringing her dainty ways, her mouse-like attention to detail, to the robust simplicity of Ulverton. England belonged to his spirit and he did not want his wife interfering, no matter how good her intentions. 'No,' he modified his tone. 'It would be too dangerous.'

'But other Norman women are there,' she objected. 'What about Felice de Remy?'

'Felice de Remy almost died in England,' Rolf said impatiently. 'Even when I sailed, she had not recovered her full strength. And not every Saxon is as good-hearted as the one who saved her life and that of her child. It is no place for you, Arlette.'

'But I want to be with you. How will I bear sons for Brize-sur-Risle if you are never here?'

'I am here now,' he said. 'Every night for a month I have sown my seed in your furrow. It is not for want of my attention that you have begun your flux.'

Her pretty mouth drooped and she lowered her eyes. 'I know, Rolf. I wish I conceived more easily. If only we could…'

'I need you to govern Brize in my absence,' he forestalled her plea. 'It is unwise for us both to be away. What if there was a storm in the narrow sea and we both drowned, or our ship was attacked by Dublin pirates? What would become of Brize-sur-Risle then?'

'I'm sorry, Rolf, I didn't think.'

He rose jerkily to his feet and walked along the river bank a little way. What he had said was true, but it was an excuse to keep her away from England. He did not want her finely manicured fingers meddling in that particular pie. He felt a twinge of conscience. Perhaps he would take her to William's court. The Duke was currently accepting the adulation of his populace at Fecamp with a bevy of English hostages in his train and a treasure house of English booty — artefacts of gold and silver, heavily crusted embroideries, books and church ornaments. Arlette would like that. She would be able to wear her new gown of green silk damask and the gold Saxon round brooch he had brought her from Ulverton. In fact, he would quite enjoy parading her before his fellow Normans. Not having borne many children, her figure was supple and slender, well suited to the new fashion for closer-fitting garments. Other men would admire her demure prettiness and feel envious of the man who possessed its obedience.

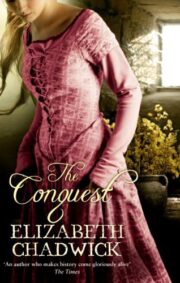

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.