'I'll be all right by then,' Goldwin said from the bed. He strove to sit up, then desisted with a groan.

'Not with a gut wound like yours you won't,' Aldred snorted.

Ailith lifted her husband's tunic and looked with dismay at the dirty bandages wound around his midriff and half-concealing a thicker wad of linen. Her stomach turned over and over as in her mind's eye she saw him upon a battlefield facing a berserker.

'Lie still,' she said as he started to protest again that there was very little wrong with him. 'Let me have a look at your injury. Certainly it needs clean bandages, these rags are disgusting. Aldred, Lyulph, why don't you go below and let Wulfhild give you something to eat?'

Aldred was all for staying at the bedside, but Lyulph, possessing slightly more tact, managed to drag him away.

'So you rode all the way from York with this wound?' Ailith asked as she unwrapped the bandages.

'It was important… if you had seen the King's face when the messenger interrupted the feasting with the news that the Normans had landed… ah!' He stiffened as she began to peel the linen wadding away from the site of the injury.

'So you were well enough to sit and feast?' she asked neutrally, her tone displaying none of her fear and anger. Goldwin had a mulish streak in his nature. Probably in the presence of her brothers he had been determined to show no weakness, to prove that he was as tough a warrior as they.

'There were others in far worse case than I. Some of them had to be borne into the hall on litters. I walked.'

The note of pride in Goldwin's voice caused Ailith to tighten her lips.

'In truth, the wound did not pain me at first,' he added. 'I rode the first three days from York without it troubling me. All I need is a short rest.'

Ailith gently lifted away the last of the wadding and looked at the wound with which Goldwin had walked and ridden for the better part of two weeks. A nasty red gash had opened him up from navel to hip-bone, slicing through layers of fat and muscle. The gash had been stitched in a rough and ready manner. Pus oozed between the threads, some of which had broken apart, and the entire area was puffy and inflamed.

'God have mercy!' Her hand went to her mouth; her belly heaved. 'Goldwin, you cannot think of marching anywhere with this!'

'Harold needs every man. He lost too many in the north,' Soldwin gasped.

Ailith opened her mouth to remonstrate with him, but closed it again, the words unsaid. It was obvious from his condition that no matter how he pushed his will, his body would be incapable. All she had to do was keep him lulled and quiet, giving his flesh the chance to knit.

'So be it,' she murmured, 'but tonight you must sleep. May I ask Sigrid's aunt Hulda to look at your wound and give you a potion to help the healing?'

Goldwin nodded and closed his eyes with a sigh. 'Indeed I am very tired,' he mumbled. 'I've hardly slept since the battle. It is the ravens pecking at the corpses. They won't leave me alone.'

Rolf slid wearily from Alezan's back to stand in the ankle-deep sludge of the wooden fort that one of Duke William's adjutants had pretentiously dared to call Hastings Castle. A bitter wind drove his sodden cloak against his back and whipped the stallion's tail between his mired hocks. The rain which had held off briefly as they rode through the marshy, deserted countryside began to whisper down again, fine in the wind as wet mist, a rain to penetrate the bones until they would never be warm again. Rolf removed his helm and absently touched a sore patch at his temple where the leather lining had chaffed.

Across the bailey the stable quarters were frantic with activity as patrols returned from a day of foraging the hinterland for provender. An outlying scouting party had galloped into the camp with the news that the English army had been sighted in the great forest known as the Andredesweald not seven miles' distance. Riders had been sent out forthwith to summon in all the outlying Norman troops, and the command had gone out to stand to arms.

Rolf led Alezan to the stables and dismissed the harassed groom who came to take the bridle. 'Go to,' Rolf said, stroking the chestnut's whiskery soft muzzle. 'Attend elsewhere before the Duke has a battle right here among his own knights.'

The man hurried gratefully away towards a swearing Breton count whose stallion had just stepped on his toe.

Alezan snuffed Rolf's hair and face, his breath moistly warm as the man rubbed him down with a wisp of balled up hay. 'Give over, you brute,' Rolf muttered as the horse lovingly nipped the back of his neck. The chestnut's coat was thickening up for winter, the golden blaze of his hide muting to red. Rolf lifted each one of the stallion's hooves in turn to check that the shoes were still securely nailed and that the frogs were clean. As he straightened from his examination, his eye was caught by Richard's grey destrier in the horse line opposite, and he paused to admire the animal.

To look at him now, it was impossible to believe how difficult he had proved on the beach at St Valery, and again at Hastings. It was as Richard said; the stallion hated ramps, but in every other way was a beast of exceptional quality. He did not have the bulk of some of the north Norman destriers with their strong influx of Flemish blood, but he was fast, could turn on a penny, and his endurance was phenomenal. Even now, after Richard had been out on him all day, he still looked fresh, his ears pricked, his liquid eyes curious. Rolf admitted ruefully that he would have to eat his pride and go cap in hand to Richard to beg him for the use of the horse at stud. In his mind's eye he saw his friend's smug grin and winced.

By the time he left the stables, the daylight was almost quenched. Torches glimmered in the wooden huts and tents of the vast Norman encampment of seven thousand men. Rolf went to one of the ramshackle cooking sheds that had been set up within the bailey. A bulky Fleming with forearms the size of hams was tending a huge iron cooking pot suspended over the flames. He stirred the contents with a large, shallow ladle, wiped his forehead on his rolled-back sleeve, and looked at Rolf.

'What you brung this time?' he demanded in heavily accented French.

Rolf held out his hands to the warmth of the fire. The smell of the bubbling, rich stew teased his nostrils and his stomach growled. 'Enough to keep your cauldron simmering for another day at least,' he said as he handed the man his wooden eating bowl, and sat down on the crude bench at the side of the cooking pot. Unbidden there came to his mind's eye a vision of the angry, bewildered peasants from whom the supplies to feed the Norman army had been reaved. He saw their village burning orange beneath the grey October sky, inhaled the dark coils of smoke, heard the wails of the women and children, the furious despair of the men.

The ravaging had been a deliberate ploy of the Duke's, an attempt to lure Harold onto the Hastings peninsula and there force him to do battle, William wisely did not want to move too far from his own precarious supply lines. He reasoned that when Harold heard of the destruction of estates whose earl he had once been, he would take it as a personal insult and his impetuous nature would bring him roaring down to the south coast, intent on throwing the Normans back into the sea. It was William's plan to persuade Harold to give battle before his troops were rested and back up to full strength after their hard battle in the north. Tonight it seemed as if that plan had worked.

The Fleming leaned over the stew to ladle a generous portion into Rolf's bowl and hand it back to him. There were greasy chunks of mutton floating in it, and a mish-mash of vegetables. Rolf cupped his hands around the bowl, savouring the heat, and sipped. A comforting warmth reached his vitals and began to thaw his limbs.

Outside the shelter the rain started to thud down hard, filling the hollows in the churned mud of the bailey floor. A boy ran across the courtyard with a torch in his hand, and disappeared into the wooden keep. Another foraging party rode in with a milch cow and bellowing calf, and a packhorse laden with sacks of flour and strings of onions. The men were swearing roughly in Flemish, cursing the foul English weather, but their manner was jovial. They had also raided a barrel of mead which Rolf knew would never find its way to the quartermaster.

Another man trudged across the courtyard towards the cauldron, his hood drawn up around his face and his body protected against the rain by a cloak of double thickness fashioned of the hairy wool preferred by the Danes.

'Stinking weather,' commented Aubert de Remy by way of greeting and accepted a bowl of the scalding mutton broth.

Rolf murmured assent and shifted along the bench to make room for the merchant. Two reconnaissance scouts on dark bay horses entered the fort at a rapid trot. Torchlight and rain gleamed on helms, harness and mail.

'Are you on duty tonight?'

Rolf shook his head. 'No, I've been on forage detail all day, but I doubt I'll sleep for all that. Do you think Harold will attack?'

Aubert pursed his lips. 'I doubt it. I believe he is planning to keep us penned up on the peninsula while he waits for more troops to arrive and strengthen his force. It is what I would do if I were him. Mind you, if I were him, I would have stayed in London and made William come to me.' He sleeved a drip from his nose and hunched his shoulders. 'Time is on Harold's side, not ours. He could have afforded to wait.'

'Not necessarily. The Pope has given his blessing to our cause. God is on our side. When word of that gets spread abroad, some of the English might not be quite so willing to fight.'

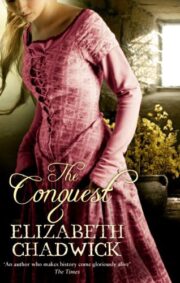

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.