A groom led a chestnut courser up to the camp fire and tugged his forelock to Aubert. Aubert acknowledged him and groaned once more. 'I never want to see a saddle or the sea again after these last few days,' he complained as he finished his food in two swift bites. Wiping his hands on his chausses, he reached for the bridle.

Rolf chuckled. 'God speed you on your way, and may it not be too rough on your backside!'

Grimacing, Aubert gingerly lifted himself into the saddle. Adjusting his stirrups, he suddenly paused and looked at Rolf. 'Felice is still in England,' he said sombrely.

'Could you not get her away?'

'She is with child, Rolf, and not carrying well. I did think about it, but if she had made the journey home with me, she would likely have miscarried and perhaps died. You know how dangerous these matters can be.'

Rolf knew that Aubert had resigned himself to the fact that Felice was barren. To have it proven otherwise, to know that she was at such risk must be devastating. Aubert adored his vivacious, dark-eyed wife. She was his pride and joy. 'I am sorry to hear it,' he said gravely. 'So she is still in London?'

Aubert fiddled with the leather stirrup strap. 'I am afraid that she is, and I am known for a spy there. My Saxon neighbour, the armourer — he and his wife have taken Felice to the convent of St Aethelburga for refuge, but I know that Harold has set a watch on the place lest I should go there seeking my wife. I would go to her if I could, but what use would I be to Felice and the child as a corpse?' He sighed heavily and, straightening in the saddle, drew on the rein to turn his horse around. 'I tell you, after this campaign, I am never going to be other than a simple wine merchant ever again!' Saluting Rolf, he guided the chestnut around the camp fire, and urged him into a trot.

Rolf rubbed the back of his neck and watched him leave, glad that he had no such burdens of his own to bear. River mist smoked around the horse's forelegs with ghostly effect. A blood-red sun pierced the dampness of the autumn morning and splashed mount and rider with ruddy gold. When they were out of sight, he turned back to the camp fire, and gave the command to begin moving out.

CHAPTER 9

'Sister Edith says that I still have at least another two months until the birth, but I know I shall burst before then,' groaned Felice, her hand upon the mountain of her belly. 'I'm as big as one of Aubert's wine barrels now!'

Ailith, who was visiting Felice at St Aethelburga's, contrasted Felice's impressive mound with her own which was no more than a gentle hillock. She too had another two months until her confinement.

'I asked Sister Edith if it could be twins, but she just laughed and said that there was a lot of water around him.'

'Him?' Ailith smiled.

'From the way he kicks me night and day, I know I am carrying a boy. Only a male could be so inconsiderate. Oh! Feel him now!' Taking Ailith's hand, she placed it over her swollen stomach. Ailith felt the vigorous thrust and surge against the palm of her hand and was both surprised and a little disconcerted.

'If what you say is true, then mine must surely be a girl,' she said. 'I have felt nothing like this — tickles and flutterings that is all. Dame Hulda says that I will suddenly swell up, perhaps in the last month.' Dame Hulda had not said a great deal, although she visited Ailith frequently to keep an eye on her wellbeing.

Felice's condition had improved tremendously since her arrival at the convent. There were two Norman nuns and a Fleming among the thirty-strong community. The Abbess herself, although English by birth, had a sister who was married to a Norman merchant, and these connections made Felice feel less of a foreigner.

The outside world intruded little upon the daily routine of the nuns. Their time was spent in prayer, contemplation and hard work. Felice, as a boarder, was not required to go to prayer at all hours of the day and night. Indeed, being in a delicate condition, she was positively cosseted by the holy women. Her security restored, Felice had recovered much of her confidence and poise. She was still terrified of the ordeal of childbirth, but for the nonce she was able to control her fear. 'He will be named Benedict,' she told Ailith dreamily. 'That was the name of Aubert's father.'

Ailith curbed herself from uttering a sarcasm concerning Aubert's loyalties. No cause would be served by making hostile remarks to Felice about her absent husband.

'Have you decided on a name for yours?' Felice asked when Ailith said nothing.

'Goldwin says Harold for a boy, Elfled for a girl.' Ailith had been sitting on the edge of Felice's bed, but now she rose and paced to the window. It was a square opening in the wall of about shoulder height, and with the shutters thrown back for fresh air and daylight, yielded a view of a swept yard containing animal pens and a well housing. Sleeves pushed back, overskirt pulled through her belt, a nun was winding the bucket. 'My brothers are home from the shore watch,' she said into the natural silence which had fallen. 'Harold could not keep the army together any longer. There has been no sign that your Duke will make a crossing yet.'

'He is not my Duke.' Felice petulantly plumped up the bolsters at her back. 'I wish he had never laid claim to England.'

'So do I,' Ailith said with a heavy heart. She watched the nun cross the courtyard with her full bucket of water. The weather was still and grey, a waiting day. Abruptly Ailith turned from the window. 'I have to go, Goldwin doesn't like me to be away for too long.' Leaning over Felice, she kissed her on the cheek.

'Come again soon,' Felice entreated.

'If I can.' Ailith forced a smile. 'God willing, this dispute between Harold and William will soon be over.' In her own ears her voice sounded false and overbright, as if she stood at the bedside of a terminally ill patient, reassuring them that they would soon be on their feet.

When she arrived home, her brothers' mounts were tethered outside the forge, and she saw that the horses were laden for a journey. Hauberks and quilted tunics were rolled up and strapped behind the saddles together with bundles of provisions. More ominously, held by a twist of leather at the horses' flanks, the heads of their great Danish war axes gave off dull gleams of light. Propped against the forge wall were two round shields and two ash-hafted spears. A third saddled horse dozed on one hip, and beside it stood her own irascible pack ass. Ailith poked her head around the forge door, but there was no-one inside and the fire was low. Goldwin's workbench was devoid of the usual clutter of tools. A feeling of dread came upon Ailith. Running to the house, she flung open the door.

Seated at the table near the hearth, Aldred, Lyulph and Goldwin broke off their conversation and looked at her, their expressions a mingling of surprise and guilt. The board was littered with the crumbs of a hasty meal. In a corner Wulfhild was sniffing and wiping her eyes on her apron.

'What has happened?' Ailith demanded. Her gaze flew to Goldwin and she saw with rising panic that he was wearing a quilted gambeson and had strapped a langseax to his belt. 'Why have you taken your tools from the forge?' On the trestle she noticed his own lightweight hauberk rolled into a bundle and secured with a leather strap. She met his eyes. 'You are going to war,' she managed to say hoarsely before her throat closed.

'Aili, I must. The King will need an armourer in the field.' Jerking to his feet, Goldwin hastened around the table and took her in his arms. 'If I stay here and brood any longer, I will explode like a barrel of overheated pitch.' His embrace tightened.

Never before had he smelled so strongly of the forge and acrid masculine sweat. Ailith saw with painful clarity the way his hair curled on his brow, the squirrel-brown of his eyes and the density of his lashes.

'I cannot bear it,' she whispered, her fingers tightening in the quilting of his tunic.

'Sweetheart, I know how you feel, but I have to go.'

'To prove your manhood?' she snapped. 'Surely there is proof enough of it here!' She pressed his hand against her belly. 'It is this you need to stay and protect, or are you going to do like Aubert de Remy and leave me to fend for myself?'

Goldwin whitened beneath the lash of her tongue. 'It is for the very reason of my unborn child that I am doing this,' he answered huskily. 'So that it may have a future. Aili, please!'

She bit her lip and laid her head against the erratic thud of his heart, her own heart leaden with terror. 'So William has landed?' she asked after a moment, when she had swallowed enough of her bitterness to be able to speak without screaming.

'No.' It was Aldred who spoke as he and Lyulph rose from their hasty meal. 'The King's brother Tostig and Harald Hardraada of Norway are ravaging the north country. York has fallen and the armies of the northern English lords have taken a severe battering. If you want to save your child, pray as never before that the winds continue to keep William of Normandy from our shores and that we can hold back the might of the Norwegians.' His mouth a tight, grim line, Aldred went to the door. 'We have no time to tarry if we are to march out before noon.'

Ailith tightened her grip on Goldwin. There was so much she wanted to say, but all of it was locked inside her, and intertwined with it was a tide of helpless rage. 'Oh, Goldwin, have a care!' she choked out.

Her lips were smothered by his kiss, hard and long. 'And you too.' His own voice was strangled with emotion.

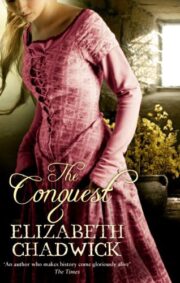

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.