Her entire body jerked with the shock of the vision and her eyes flew open, a scream stifled behind her lips.

She heard voices and the clump of footsteps on the hatchway stairs, and sat up. Her heart thumped against her ribs in rapid strokes and her cheeks were damp, not only from her hair. Even in sleep she had been weeping.

By the hazy light of the single lantern, she saw Benedict and a sailor carrying Mauger between them. His blond head sagged, his mouth lolled open.

'Mauger… Oh Jesu, is he dead?' Julitta was unable to move, could only watch with widening eyes as they brought him over to her.

'No,' Benedict said, his voice constricted by the effort of setting Mauger carefully down on the hay, 'but he's barely breathing, and this gash on his head is still bleeding.'

Julitta stared at her husband, at the shallow rise and fall of his chest, the blue tinge to his flesh, the red trickle from the deep gash in his forehead. She reached out her hand and took hold of one of his. The fingers were as cold as effigy-marble.

Benedict studied her for a moment with brooding eyes. 'I'll go and fetch Sampson,' he said. 'He's one of the crew members, but he once trained for the church. It is the nearest Mauger will get to a priest.'

Julitta silently nodded, and did not look up as he turned and left.

Mauger was shriven by Sampson, who, despite having given up the church more than ten years ago, was still comfortingly familiar with its rituals. Certainly Mauger did not seem to notice the difference as he weakly made confession and was absolved of sin.

For the rest of the day, watched over by an exhausted Julitta, Mauger drifted in and out of consciousness, but never regained coherence. His grey eyes were opaque and unfocused, his breathing rapid and shallow. Just before midnight, in the presence of herself and Benedict, it stopped altogether.

Julitta composed Mauger's hands upon his breast and drew the blanket up to his chin. His eyes were closed and he looked as if he fallen from utter weariness into sound sleep. She bowed her head, unable to weep, for she had wept herself dry before he was found.

'He tried to be good to me in his way,' she said. 'Only I never wanted to wed him; never gave him a chance.'

'It isn't your fault,' Benedict said sharply, alarmed at her response even while he understood it.

'But it is. He was always trying to prove himself to me. I made him lose his judgement. He would never have bought that horse of his own accord.'

Benedict looked at her with pain in his eyes. He well understood her attitude. After Gisele's death, he had felt the scourge of guilt, still did on occasion if he had the time to brood. 'Grief heals,' he said, laying his hand upon hers. 'Guilt destroys.'

'Playing the priest again?' she bit out, and flashed him a glance full of anger. But there was misery there too, and need.

'No, just a man who lost the wife he had wronged before he could make atonement,' he said.

She flinched as his pain pierced hers. 'I'm sorry,' she said in a small voice with a break at its edge. 'I didn't think.'

'Ah, Julitta.' He folded her in his arms, and she accepted the embrace, her body stiff and hesitant. 'I don't want to lose you too. All our lives we have been coming together and breaking apart.' He swallowed, then raised one of his hands to touch her gaunt, hollow face. 'I want you, Julitta, not your guilt, not mine, just the two of us, and a new start. No,' he added, as she opened her mouth to speak. 'Now is not the time. We still have Mauger to honour and lay to rest, and there is grieving to be done. Let the time turn under heaven. Just think on what I have said.' Gently he released her, and went up on deck to fetch such things as would be needed for the washing and laying out of a corpse.

Dry-eyed, Julitta gazed upon the body of her husband and wished that she could weep.

CHAPTER 60

BRIZE-SUR-RISLE, SPRING 1088

Julitta knelt at the feet of the statue of the Magdalene Mary in Brize's convent. The flagged floor was cold beneath her knees, and the breath of her prayers broke from her lips in puffs of white vapour. This was Arlette's domain. Even in death, her father's wife dominated the place. Not content with the small chapel dedicated to her beyond the high altar, her presence pervaded the rest of the church. The wood and ivory statue of the Magdalene was clad in a green robe, a neat white wimple framing a vacant, half-smiling face, its complexion made luminous by the glow of the sanctuary lamp.

A thick wax candle burned on a spike. Beside it, in a specially cut niche, a pyramid of votive tapers flickered, each one a prayer for the souls of Arlette de Brize, her daughter Gisele, and now for Mauger of Fauville. Julitta crossed herself, rose from her knees, and lit another taper to add to those already burning. Since her return, she had made it her daily ritual to visit the church and pray for the soul of her dead husband.

Coming to terms with his death had been difficult, because it had meant coming to terms with herself and the guilt which Benedict had warned against. She could well recall the bitterness and rage of her childhood on discovering that the world did not revolve around herself alone, and that a hitherto unknown half-sister had laid claim to all that Julitta held dear — her standing in the world, her father's love, Benedict. She had hated Gisele even without knowing her. There had been a dark triumph in lying with Benedict, in taking him from her sister. A fleeting victory, paid for a hundred times over by her marriage to Mauger — and Mauger had done much of the paying.

Outside, a February dusk was gathering strength, the light a pale grey-blue. With a sigh, Julitta adjusted her cloak and walked towards the open doorway. Before she could reach it, she heard the snort of a horse and the ring of hoof on stone. Freya whinnied and was answered by a low, stallion nicker. Julitta's heart began to thump. But it was her father who stepped inside the church and made the sign of the Cross on his breast, and she was aware of a pang of disappointment.

He was nine and forty now and still handsome, although he wore the lines of his years and the brilliance of his hair had faded to a dusty ginger. During her absence, he had begun negotiating to marry a widow twelve years younger than himself, a merry, handsome woman with three children to her credit and a dowry as magnificent as her bosom. Julitta approved of the Lady Amicia. At least she need not worry about her father. There was a twinkle in his eye and a bounce to his stride.

'Daughter,' he acknowledged. 'I knew I would find you here.'

'I was about to leave.'

He nodded. 'It'll be dark soon.'

His way of saying that she had stayed too long. She knew that he had come to fetch her. Praying at his wife's tomb in the winter dusk was not one of her father's habits.

'Wait but a moment and I'll accompany you back,' he added, and went to bow his head at the altar and light four candles to add to the pyramid — one each for his wife and daughter, one for Mauger, and one for Ailith. A nun appeared from a recessed doorway, respected the altar, then Rolf, and went to trim the sanctuary lamp and attend to the candles. He crossed himself, left the woman at her task and returned to Julitta.

She eyed the nun wistfully. 'I wish that I possessed such tranquillity,' she murmured.

Rolf took her arm and led her out to the horses. The air was dank and raw, the trees bare and black. 'It will come,' he said. 'You are too impatient with yourself.'

Julitta gave him a bleak smile. 'Whose trait is that?'

'Assuredly your mother's.' He cupped his hand to boost her into the golden mare's saddle.

'Not yours?'

'I am merely impatient with others.'

'Then it seems I have both failings.' She settled herself in the saddle and took up the reins.

'And a stubborn will, too,' he said.

They rode in silence for a while, until the stone keep of Brize rose from the landscape, its high windows flickering with torchlight. Smoke wisped from the cooking fires in the bailey, promising food and comfort.

Rolf said softly, 'You are younger than your mother when I first knew her. You have all your life before you.'

'As she had hers?' She was shocked at the bitter note in her own voice.

Rolf winced. 'There was a time when we had great happiness,' he said. 'I know that what happened later was my fault. If I could undo it, I would.' He eyed Julitta's wooden expression. 'I still think of her, I still miss her. The regrets are carved so deep they are always with me, but I have learned to live with them. What use is there in looking back except to gain the experience of hindsight?' His hand rose to touch his cloak fastening – a brooch in the shape of Odin's six-legged horse, Sleipnir.

'So, what would you have me do?' She dismounted rapidly, a sure sign that she was agitated. 'Return to my old, hoyden ways?'

'That is not what I meant and you know it.' Rolf swung himself out of his saddle. His knee joints ached, and he had to flex his legs several times before the stiffness eased. 'All I am saying is that if you are going to drag a cross around with you, there is no need to carry it so high that you can't even see where you're going… or who walks beside you. In God's name, daughter, go with Benedict now and make your life with him. You have my blessing. Indeed, if you weren't so contrary, I'd order you to it.' He looked her up and down, exasperation and humour in his eyes. Then he said calmly, 'He would have come to the chapel himself, but I wanted to see you first.'

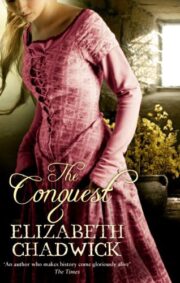

"The Conquest" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Conquest". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Conquest" друзьям в соцсетях.