‘Long live our great and wise leader, Mao,’ Kuan said urgently.

‘Long live our leader,’ Chang echoed.

The doubts were there in those four words. His own ears could hear the weakness in them, little worms of disbelief burrowing deep, but Kuan’s eyes sparkled with conviction, satisfied with his echo. Her neat little ears had not detected the worms.

Chang rose to his feet and drew a long slow breath, stilling the unsettled beat of his heart. In front of him the mountain fell away steeply to the narrow gulley below and rose again in a sheer bleak rock face on the opposite side. No villages or cart tracks or even wild goat trails in sight, just the empty treeless landscape strewn with rocks cocooned in ice, and the twin snakes of silver metal that cut through the base of the valley. The rail track.

For a brief moment he allowed himself to wonder how many Chinese lives had been lost, how many rockfalls had come crashing down on their heads, turning the rails red as they were laid on the ground. It was the fanqui, the foreign devils, who dynamited its path through the valley. They’d come and stomped all over China. They laid down their metal roads, indifferent to the voice of the land itself, their big elephant ears deaf to the anger of the spirits of the mountain.

First the European uniforms marched over the land, swarming like flies across the yellow dust and stealing its wealth, but now it was the Nationalist Army of that strutting peacock, Chiang Kai-shek. He was tearing everything from under the feet of the Chinese people, even the grass in their fields and the green shoots in the paddies. It made Chang An Lo’s heart ache for them and for this vast and beautiful Middle Kingdom.

‘Kuan,’ he said, tasting ice on his lips. ‘Contact Luo, then Wang. Tell them to lay the charges.’

The young woman at his side slid the khaki canvas burden from her shoulder to the ground and began to unbuckle its straps, turning the dials with efficient skill. Kuan had trained as a lawyer in Peking but now was a radio expert, and it was her job to keep the various Communist cadres in constant touch on this mission. She worked well, with no fuss. This pleased Chang and made her an easy companion. He trusted her. Her only weakness was her lack of stamina in the mountains.

As she murmured into the mouthpiece, he closed his eyes and opened his mind. He turned his face northward, directly into the bitter wind that raced down from Siberia, and he breathed it deep into his lungs, let its teeth bite at the soft tissue within him.

Was she there? His fox girl. Somewhere across the border in that foreign land?

Could he taste her in the Russian wind? Smell her? Hear the clear bell of her laughter?

He wouldn’t say her name, not even inside his mind. For fear that the whisper of it would betray her and bring the forces of vengeful spirits down on her copper-fire head. She had stolen something from the gods and they did not forgive.

‘It is time,’ he said with an abruptness that took Kuan by surprise.

‘Now?’ she asked.

‘Now.’

Quickly she buckled up the canvas straps, but by the time her cold fingers had finished the job, Chang was already moving fast down the mountainside.

Death. It seemed to stalk him. Or did he stalk it?

All around him bodies lay torn to shreds, limbs and torsos blasted to limp chunks of flesh and bone that were attracting crows before they were even cold. One head, a young man’s with black blood-streaked hair and one eye missing from its socket, perched on a boulder ten metres from the wreckage and stared straight at Chang. A head, no body. Chang felt the finger of death touch his heart till he shivered, turned away and walked down the broken line of the train. Glass crunched under his feet.

Carriages at both ends had been blown apart by the dual explosions. Ripped open into a raw and tangled twist of metal and timber; bodies spewed out like wolf-bait on the icy ground. As Chang prowled past the carnage he hardened his heart against the screams and reminded himself that these men were his enemies, travelling south with the sole purpose of slaughtering Communists, determined to destroy Mao’s Red Army. But somewhere deep beyond his reach, his heart wept for them.

‘You.’ He pointed at a young soldier in the grey uniform and red armband of the Chinese Communist forces, who was dragging a bleeding figure from the wreckage. The wounded man was a Nationalist Army captain, judging by the colours he wore, and his gut had been torn open by the explosion. He was trying to hold in his bloody innards with his hands, cradling them, but one end of his intestines had slipped from his grasp and trailed behind him. It was unwinding as the young Communist pulled him free, yet the Nationalist captain didn’t scream.

‘You,’ Chang said again. ‘Stop that. You know the orders.’

The young soldier nodded. He looked as if he would vomit.

‘Only those who can walk will travel with us. The rest…’

In a slow, reluctant movement, while Chang stood over him, the young soldier slung the rifle off his back. Despite the ice in the air, sweat formed on his brow. He had the heavy features and broad hands of a farmer’s son, a peasant away from home for the first time in his life. And now this.

Chang recalled his own first killing, seared into his soul.

The soldier nestled the rifle to his shoulder exactly as he’d been taught, but his hands were shaking uncontrollably. The man on the ground didn’t beg, just closed his eyes and listened to the wind and to what he knew would be the last beats of his heart. Abruptly Chang drew his own pistol, leaned down to the captain, placed the muzzle at his temple and pulled the trigger. The body jerked. Chang bowed his head for a split second and commended the man’s spirit to his ancestors.

Death. It seemed to stalk him.

The train’s massive steam engine had bucked off the damaged track and plunged nose first down the bank, but just managed to stay upright. Behind it lurched the baggage wagon at an odd angle, but the only baggage it was carrying came in twenty long wooden boxes, four of which had splintered open in the crash. Chang’s heart raced at the sight of them. He leapt inside the wagon, feet braced against the buckled slope of the floor, and rested a hand possessively on one of the open boxes.

‘Luo,’ he called.

Luo Wen-cai, the young commander of the small assault force, clambered up awkwardly after him. A slow-healing bullet wound in his thigh hampered his usual quick movements, but nothing hampered the grin that shot across his broad face.

‘Chang, my friend, what treasure you have found for us!’

‘Tokarev rifles,’ Chang murmured.

This was even better than he’d expected. This haul would please Chou En-lai at Party Headquarters down south in Shanghai, and put rifles where they were needed – in the military training camps; in the fists of the eager young men who came to fight for the Communist cause. Chou En-lai would preen himself, and sharpen his tiger claws as if he’d hunted them down himself. This success would gain him even greater support from the mao-zi, the Hairy Ones.

The mao-zi. The words stuck in Chang’s throat. They were the European Communists, the ones who held the purse strings of the Chinese Communist Party. They were represented by a German called Gerhart Eisler and a Pole known as Rylsky, but both were mere mouthpieces for Moscow. That’s where the funds sprang from and where the real power lay.

Yet here was a train carrying troops and arms from Russia to Chiang Kai-shek’s overstretched Nationalist Army, who were sworn enemies of the Chinese Communists. It didn’t make sense, whichever way Chang turned it. Like a dog humping a goose, it wouldn’t fit together. He frowned, feeling a sudden unease, but nothing could dampen his companion’s delight.

‘Rifles,’ Luo crowed. He scooped one out of a box and ran a hand down its length, lovingly, the way he would a woman’s thigh. ‘Beautiful well-oiled little whores. Hundreds of them.’

‘This winter,’ Chang said with a grin for his friend, ‘the training camps in Hunan Province will be stocked as tight as rice in a tu-hao’s belly.’

‘Chou En-lai will be more than satisfied. It’ll do us no harm either to be the ones to bring him such a harvest.’

Chang nodded, but his thoughts were chasing each other.

‘Chou En-lai is a genius,’ Luo added loyally. ‘He organises our Red Army with an inspired mind.’ He lifted the rifle and sighted down its barrel. ‘You’ve met him, haven’t you, Chang?’

‘Yes, xie xie, I had that privilege. In Shanghai, while I was attached to the Intelligence Office.’

‘Tell us what the great man is like?’

Chang knew Luo wanted big words from him, but he could not find them on his tongue, not for Chou En-lai, the leader of the Party Headquarters in Shanghai.

‘He has the charm of a silk glove,’ he murmured instead. ‘It slides over your skin and holds you firmly in his grasp. A thin, handsome face with spectacles that he uses to cover his… thoughtful eyes.’

Slavish eyes. Slavish yet ruthless. A man who would do anything – anything at all, however brutal to others or demeaning to himself – for his masters. And his masters were in Moscow. But Chang said none of this.

Instead he added, ‘He’s like you, Luo. He has a mouth as big as a hippo’s and likes to talk a lot. His speeches run on for hours.’ He banged a hand down on one of the boxes. ‘Now let’s get these loaded on the pack animals before-’

A sudden explosion silenced his words. A dull thud outside that rattled the boards of the wagon. It came from somewhere close and both men reacted instantly, springing from the wagon, pistols in their hands. But the moment they hit the ground, feet scrabbling for grip on the ice, they halted – because immediately ahead of them, lying helplessly on its back among the rocks like an upturned turtle, was a tall metal safe. Its door had just been blown off and around it huddled an excited group of Luo’s troops.

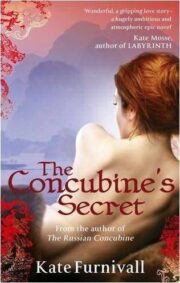

"The Concubine’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Concubine’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Concubine’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.