‘Nyet. Of course not.’

‘Good. Leave us then, Igor.’

The plump face creased with concern and Alexei had the feeling the young man did not much appreciate being dismissed as if he were a schoolboy. Nevertheless he left with no further objection, just shut the door a shade harder than was necessary.

‘Come over here, my friend.’

Alexei approached the bed. It struck him as a strangely intimate act in the presence of a stranger and he became aware of the smell of the bedsheets, the blue veins bunched at the base of the ageing throat. A closer look disclosed a man considerably frailer than the voice he chose to use. Strands of grey hair were scraped severely back from his face which, despite being fleshy, had sunk in on itself, falling into crevices, crowding around the dark eyes.

‘I’m not dying,’ the sick man announced gruffly.

‘I’m glad to hear it. But it’s your friends on the other side of that door you need to convince, not me. They’re out there whittling your coffin right now.’

The man laughed, a great guffaw that had him rubbing his hand on his chest as if it pained him under his nightshirt. ‘What’s your name, comrade?’

‘Alexei Serov.’

‘Well, Alexei Serov, you don’t look much like a guardian angel to me, but I thank God for putting you in that street last night, especially when I had dismissed my companions for the evening.’ His mouth twisted in a grimace. ‘This experience will teach me to avoid brothels in future.’

Alexei sat down on the chair beside the bed and smiled. ‘Our paths crossed, friend. I was there at the right time. Now you’re safe with your people, so get well again.’

‘I intend to.’ He held out his hand to Alexei. ‘Accept the sincere thanks of Maksim Voshchinsky.’

Alexei shook the hand. It felt surprisingly firm in his and he respected the strength of will that made it so. But his eyes were drawn to where the sleeve of the nightshirt had ridden up and the muscular forearm lay briefly in view. What he saw there slowed his heartbeat. A fleeting glimpse, that was all, before Voshchinsky withdrew his hand once more, but it was enough to tell Alexei this was someone to keep far away from.

Voshchinsky’s hooded eyes conducted a slow inspection of Alexei’s appearance. ‘Most people as dirty and ragged as you, Comrade Serov, if you don’t mind my saying, would have had my watch in their pocket, my wallet in their hand, and left me to die alone on the ice.’

Alexei rose to his feet. ‘Not everyone is like that,’ he said with a polite bow. ‘But you must rest now. Don’t tire yourself. I am happy to see you are recovering well. Comrade Voshchinsky, I wish you good day.’

He walked to the door, eager to be out of this room with its winter light glinting off a multitude of glazed staring eyes. The sound of the man’s shallow breathing followed him.

‘Wait.’

Alexei paused.

‘Comrade Serov, are you in such a rush to be elsewhere?’

‘Nothing stands still in life, my friend.’

The grey head nodded again, lolling slightly on his neck as though it were too heavy. ‘I know.’ He smiled, a brief, forgiving twitch of his lips. ‘Especially when you are young.’ Sadness rustled like dry leaves in his words and the fingers of one hand slowly opened and flexed on the sheet, an unconscious movement, as if trying to grasp at Alexei. Or maybe at life. ‘But I am not ready to see you go yet.’

‘You have your friends.’

‘Yes, that’s true. They are good friends. I can’t complain. They do what I say.’

With a quiet click Alexei opened the door. Outside on the polished boards stood the three men and at the sight of him all three took a step forwards. They wanted to know what had been said in there but, in that moment when he could have walked away, back to the fleas and the prospect of never seeing his own father again, he felt a shift within himself. Through his own arrogance on the bridge in Felanka he had lost everything that would open the doors to set Jens Friis free. But now he couldn’t allow himself to walk away from the strange room with the dead birds and the sick man. This time he must swallow the arrogance. Bend the knee. Take the risk.

‘He’s resting,’ Alexei announced. Then he entered the bedroom once more and softly shut the door behind him.

‘So?’ It came from the bed.

‘You say your friends do what you say. Because I saved your life, would they do what I say? Would they owe me that?’

Voshchinsky frowned, a wary pucker of his heavy eyebrows. Alexei returned to the chair and sat down.

‘Maksim,’ he said, ‘you have many friends.’

He lifted the man’s hand in his own, touched the veins that ran like serpents under the skin, and slid the nightshirt sleeve up the forearm. Underneath it writhed more serpents, black ones. Two of them slithered round the base of the slender skeleton of a birch tree, their eyes red, their fangs sharp as knife blades. Beneath them, written in elaborate italic script, were three names: Alisa, Leonid, Stepan.

‘A fine tattoo,’ Alexei commented.

Maksim Voshchinsky touched the trunk of the tree lovingly with the finger of his other hand. ‘That was my Alisa, the mother of my sons, God rest her soul.’

‘Maksim, we must talk. About the vory.’

The sick man’s eyes narrowed and his voice grew rough. ‘What do you know about the vory?’

‘They are the criminals of Moscow.’

‘So?’

‘And they wear tattoos.’

35

Lydia stood on the steps of the Cathedral of Christ the Redeemer in the thin sunshine. The Moskva River slid past, boats bobbing on the molten silver of its surface, and she’d counted twenty-two of them in the hour she’d been waiting.

‘Alexei,’ she murmured, ‘I can’t wait any longer.’

She’d really believed it today. That he would come. When she said to Liev, ‘My brother will be there,’ for once she hadn’t been annoyed by his big laugh, because now she knew for certain that Alexei had received the letter she’d left in Felanka and that he wanted to see her again. It had lifted a dead weight that lay in her stomach as solid and cold as the tombstones in the Cathedral’s crypt. She was alone on its wide steps. No one loitering in the street or slowing their pace as they walked along the pavement. Everyone seemed to be going about their own business as normal, an elderly man with a fat dog in tow, a young woman with a net bag and a child hanging off each hand. Lydia studied the street intently. It was hard to shake the chill of being observed.

After twenty minutes she had convinced herself that no one was watching her, but even so she intended to take a circuitous route across Moscow. First in one of the horse-drawn carriages, an izvozchik with the horse still wearing its summertime hat, its ears sticking up through the plaited straw like curious weasels; then a tram, an intricate weaving through shops, in and out of side doors, another tram, another shop, a final quick desperate dash on foot. Then the park. She had it all planned.

Lydia had run the last stretch and her heart was somewhere in her throat. She made her way along the path, everything around her so piercingly bright that she had to narrow her eyes against the sunlight. On each side stretched pristine lawns dressed up in lacy layers of snow. Ragged edges marked the boundaries between paths and lawns, as if the black earth were peeking out from under its white blanket like a sleepy mole to test the temperature outside. Lydia hurried her pace. She couldn’t see him.

She had entered the park from the Krymsky Bridge end but Chang An Lo might easily approach from a different direction. She kept turning her head, searching. Years earlier the site had been just one big scrap heap for old metal, where scavengers used to prowl at night and stray packs of dogs scraped out dens, but the land had been cleared and flattened – first for the Agricultural Exhibition and then, in 1928, turned into the Central Park of Culture and Leisure.

There was no sign of culture but people were certainly taking advantage of the leisure. The sun had tempted them out into the crisp cold air, well-swaddled figures strolling arm in arm and children scampering like kittens, released from the confines of their cramped living quarters. One athletic-looking man was kicking a ball to five young boys, all dressed in Young Pioneer uniforms with Communist-red scarves, flashing bright as robins on the snow. Such an ordinary sight, a father playing with his children, yet Lydia felt a sharp tug of envy and hated herself for it, for that weakness she couldn’t seem to escape.

Moving on through the park, past the lily-of-the-valley electric lights, she started to lose confidence with each step. This was all wrong. The park wasn’t at all what she’d anticipated when she put it forward as a meeting place. She cursed her own ignorance. She’d imagined there would be trees and tangled undergrowth, offering privacy and shadowy nooks where two people could speak without being observed, but the Central Park of Culture was still new, with wide empty stretches of grassland and flowerbeds barren under the snow, the trees freshly planted and no taller than herself. It didn’t take her long to see that Chang An Lo was not here.

The realisation slid sharp as ice into her skull. She closed her eyes, the fingers of sunlight almost warm on her lashes.

Where are you, my love?

She breathed quietly, letting loose her thoughts. When something in her mind unknotted, she knew she’d been looking for the wrong thing. Slowly she retraced her steps, scanning the ground this time instead of the Muscovites at leisure, and she saw the sign when she was back where she’d started. She smiled and felt a whisper of wind ruffle her hair. The sign was a tiny pile of stones, so small it was barely noticeable. But Lydia knew. Knew without doubt. When she and Chang had been separated in China, they had left messages for each other in a place called Lizard Creek and those messages had been buried in a jar beneath a cairn of stones. This, she realised, was her new Lizard Creek.

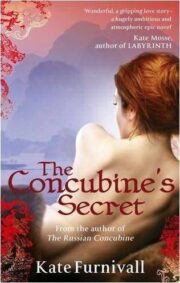

"The Concubine’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Concubine’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Concubine’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.