‘Your name, comrade?’ he asked.

‘Konstantin Duretin. Yours?’

‘Alexei Serov.’

‘Well, Comrade Serov, what were you doing swimming in the river with the fish in the middle of winter?’

‘Fish?’ Alexei frowned. Images battered his brain. A game of chess, a long-stemmed pipe. The curve of a road to a bridge.

Dear God, the bridge. Men coming at him from all directions. With a jolt of memory he slid a hand down to his side and felt the bulk of bandages there.

The blue eyes were still smiling at him, but more thoughtful now. ‘I did the best I could for you. As good as dead, you were. I found your carcass clinging to a scrap of wood in the middle of the river like a drowning kitten. Lost all but a cupful of blood, I’d guess, and near frozen to death.’

‘Spasibo, Konstantin. I owe you-’

‘Hush, rest now. I’ll cook us some fish and we can get some food into you at last. You’ve not eaten for weeks.’

‘Weeks?’

‘Da.’ He stood up.

‘Weeks?’

‘Da. I managed to get some water into you and a little soup but nothing more.’

‘Weeks?’ The word had stuck in Alexei’s mind.

‘Yes, nearly three weeks it’s been. You’ve had a fever. Thought I’d lost you more than once.’ He thumped a hand on the table. ‘But you must be made of good strong oak like my Red Maiden here.’ He laughed.

The noise of it set up a vibration in Alexei’s head and he closed his eyes to stop his brains spilling out.

The smell of grilled fish permeated the dusty cabin, ousting even the stink of the kerosene. They ate slowly and in companionable silence, the job of manoeuvring a fork to his mouth taking all of Alexei’s concentration. Konstantin left him to it but when they had finished and coffee was once more in his hands, Alexei rested back and scrutinised his host.

‘Why did you take care of me?’

‘What was I meant to do? Chuck you back in the river like a poisoned fish?’

Alexei smiled. The muscles of his cheek felt stiff, made of cardboard. ‘Some would have. Under Stalin’s system of informers, people have become afraid of strangers.’

Konstantin returned the smile. ‘I was glad of the company.’ ‘Where are we now?’

‘Downriver.’

‘South of Felanka, you mean?’

‘Da.’

‘How long have we been travelling?’

‘Ever since I picked you up.’

‘Three weeks. Chyort!’

‘Wrong direction for you?’

‘Yes. I have to return to Felanka.’

Konstantin looked away and there was a moment of awkwardness that made Alexei feel ungrateful. To cover it, the boatman reached into a drawer under the table top and pulled out a small knife and a piece of wood, then proceeded to whittle away at it, his blond eyebrows knit in concentration.

‘What’s in Felanka that is so important?’

‘Some business I have to attend to.’

His gaze lifted to Alexei. ‘Girl business, you mean?’

‘Not that kind of girl business. It’s my sister. She’s in Felanka.’

‘Ah, my friend, then there’s no rush. A sister can wait.’

Can you, Lydia? Can you wait?

Lydia was forced to wait. Despite her constant daily hammering on the station master’s hatch, it was two weeks before she was allocated a seat on a return train to Felanka. What surprised her was how easily she filled the days. She expected herself to be pacing the pavements with impatience, frantic and fretting, but no, it wasn’t like that. She sat quietly. On a station platform, in a park, in a hotel room.

She taught herself stillness.

When finally the train heaved itself into the station the compartment was full, but this time with more women than men. Conversations concentrated on the lack of goods in the shops despite rationing, and the length of the bread queues. Before boarding, Lydia had seen a chain of prisoners loaded at the last minute into the baggage van, but so carefully guarded that she had no chance to get anywhere near them. Their heads were already shaven against lice. That came as a shock. The idea of Papa without his flowing fiery locks. The image just wouldn’t stay inside her head. She became aware of a young girl next to her, small and slight. She was travelling alone, much the same age as Lydia herself, but her fragility made her seem younger. Lydia took out a cone of sunflower seeds that Elena had thrust into her bag, and offered it.

‘Hungry?’ she asked the girl.

‘Da.’ She took a handful. Her face was thin and nervous. ‘Spasibo.’

‘Travelling far?’

‘To Moscow.’

‘That’s a long journey. But it must be exciting for you.’

‘Yes, you see, I won a prize. I was the fastest maker of copper pots in my factory. So I am to receive a medal.’

Lydia blinked. ‘That happens?’

‘Oh yes, of course. Workers are always rewarded for dedication. Sometimes even by Stalin himself.’ Her young eyes gleamed with anticipation. ‘It’s to be awarded in a big ceremony in the Hall of Heroes.’

‘Congratulations. You and your family must be very proud.’

‘We are… but I’m told Moscow is dangerous.’

Lydia looked at her with interest. Didn’t the girl know that in Stalin’s Russia, everywhere was dangerous?

‘In what way do you mean?’ she asked.

The girl leaned closer, eyes wide. ‘The city is riddled with criminals.’

Lydia laughed, she couldn’t help it. ‘Every city is riddled with criminals, no matter where you go. It’s always the same.’ She noticed that a man in workman’s clothes further along the bench seat was openly listening to her. She added quickly, ‘But I know Comrade Lenin has taught us all to share what we have, even our apartments. Crime is no longer necessary. Not like it was under the bourgeois system of exploitation.’

She almost smiled. Her brother would be proud of her. You see, Alexei, I’m learning. Really I am.

The girl said nothing, just chewed on the seeds, then glanced sideways at Lydia from behind her thin blonde hair. ‘They are well known,’ she murmured. ‘With tattoos. A criminal fraternity. The vory v zakone, they’re called.’ She lowered her voice to a faint whisper. ‘That’s why I’m nervous of going to Moscow.’

A criminal fraternity? Tattoos?

No. Not again. Not China all over again. Lydia’s pulse thudded in her throat. Thank God she wasn’t heading for Moscow.

‘I’m sure you’ll be well cared for,’ she smiled reassuringly and patted the girl’s arm. ‘Someone as special as you will be kept safe.’

The look of relief on the thin face was worth the lie.

The rain had stopped and the landscape stretched away into the mist, dismal and damp. Everything looked different. How would she know when the train was close to the Work Zone? There was nothing here that marked out one featureless place from another, and now that the clouds had descended so low it was impossible to see where the forest had been levelled. This mist had swallowed all signs, a grey thief that had stolen her hopes.

Lydia was standing at the carriage window, fingers wiping away the moisture of her breath on the glass. The Work Zone had to be here, somewhere here, she was sure. She peered out intently, searching for even a hint of the matchstick watchtowers, but all she saw was a dead blanket of low cloud that, as the train raced past, curled and swayed like a drunk unsteady on his feet. The red handkerchiefs, the bright scarlet birds? Would they be visible? But no. Nothing broke the colourless monotony. She rested her forehead against the glass, felt the vibrations rattle through her brain.

She closed her eyes, remembering Chang’s words: ‘You must focus, my love, draw the parts together into a whole. Then you will be strong.’

Focus.

She opened her eyes, forgot the mist and the forest, and focused on the stretch of rocky ground nearest the track. For the next twenty-five minutes she didn’t let her gaze stray, but kept it riveted on the few metres of terrain that bordered the rail as the engine thundered through the damp air. Slowly she felt her mind change. It grew lighter. The weight of other thoughts and fears slid away until all that existed was the rock and the earth speeding past. They threaded dark lines through her mind.

Then it was there. The sign.

She blinked and it was gone. But she’d seen it and didn’t need to see it again. Rocks had been placed in a pattern, an arrangement of stone that spelled out a word and a number. The word was Nyet. The number was 1908.

Nyet. 1908.

Lydia didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. She had no idea what it meant.

17

Alexei woke in total darkness. The timbers creaked around him and he could hear the slap of the waves on the bow.

‘Konstantin!’

He heard movement in the cabin.

‘What is it, my friend? Wait while I strike a match.’

A flame flared and a lamp hissed. In the sudden gleam of yellow light Alexei focused on the jumble of blankets on the floor and realised it was Konstantin’s own bed he had usurped. The boatman was naked, his long back well muscled, blond curls on his thighs. He turned and studied Alexei, unabashed by his own nakedness, his blue eyes still heavy with sleep.

‘What is it, Alexei? A nightmare?’

‘No. Where is my moneybelt, Konstantin?’

The long eyelashes blinked. ‘Moneybelt? What moneybelt?’

‘I was wearing one when-’

‘My friend, I am no thief.’

‘I’m not accusing you.’

‘That’s what it sounds like to me.’ He spread his broad hands as if to show there was nothing hiding in them. ‘When I dragged you out of the water, you were in a mess. Bleeding over everything, your clothes cut and torn, but there was definitely no moneybelt.’ He chuckled softly. ‘Do you think I wouldn’t have noticed?’

Alexei collapsed back on the pillow and closed his eyes. ‘I apologise, Konstantin. Please go back to sleep.’

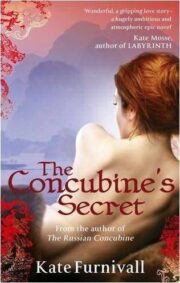

"The Concubine’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Concubine’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Concubine’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.