The line turned on her.

‘Nyet.’

‘Wait your turn.’

‘My boy needs to go but he doesn’t complain. You should know better.’

Antonina’s deep-set eyes blinked. Her mouth looked fragile. She shook her head and as one hand started to scratch the back of the other, a tiny thread of crimson appeared on the white cotton.

‘Comrade Antonina,’ Lydia said pleasantly, as she stepped out of the queue, ‘you can take my place.’

The child’s mother gave her a quick look of disapproval.

‘Comrade,’ she said, her tone quiet and reasonable, ‘we no longer have to let worthless parasites, like this woman in her bourgeois finery, steal our rights from us. She is clearly not a worker. Just look at her.’

Everyone stared at the pale pampered face, at the ruby earrings nestling in the dark hair and at the luxurious fur coat.

‘It’s obvious she is-’

Lydia interrupted. ‘Please, comrade. Pozhalusta. This is not harming you. I’m giving her my place in the queue, so-’

‘Young girl,’ the child’s mother said with interest, ‘what is your name?’

Lydia’s mouth went dry. ‘My name doesn’t matter. It is no concern of-’

The woman pulled a small blue notepad from her pocket. Attached to it by a rubber band was a pencil.

‘Your name?’ she repeated.

The Commandant’s wife said abruptly, ‘Enough of that, comrades. ’ She half turned her head, raising a gloved hand, and immediately one of her uniformed travelling companions appeared like a shadow at her side. He said nothing. He didn’t need to. The women stared at the floor. Lydia didn’t wait for more. She squeezed past his bulk and headed back towards her compartment, but as she approached it she saw the second of the woman’s uniformed guardians blocking her path.

‘Excuse me,’ she said politely.

He didn’t move. Just rested his hand on the gun holster at his hip. He was tall with fine Slavic features and a high colour to his cheeks. His dark eyes were amused.

‘Tell me, girl,’ he asked, standing too close and scanning her coat, her shoes, her ugly hat, ‘what is your interest in our Comrade Commandant’s wife?’

Lydia shrugged. ‘She’s nothing to me.’

‘I’m here to make sure it stays that way.’

‘That’s your business, comrade. Not mine.’

His eyes were no longer amused, but after a long stare he stood aside to let her pass. His uniform smelled stale, as though it had been slept in too many times. She felt his eyes bore into the back of her head as she scurried on down the corridor.

By mid-morning it was raining hard, a grey sleeting downpour that rattled like buckshot against the windows. Without warning as they were crossing a wide flat plain, the train started to slow with disconcerting jerks, the brakes shrieking and clouds of steam swirling alongside. Outside, the world blurred.

A small station with wooden roof-boards and rusting iron railings slowly slid into view, and Lydia felt her pulse quicken the moment she caught sight of the sign. Trovitsk. This was the station for Trovitsk labour camp. No one was allowed off the train here under the eagle eyes of the armed soldiers, unless in possession of an official pass. Nevertheless Lydia rose from her seat.

‘Where are you going?’

‘Don’t worry, Alexei. I’m just stretching my-’

‘You can’t get off here.’

‘I know.’

‘It’s raining. She’ll be in a hurry.’

Lydia glanced down at her brother, at his intelligent green eyes. He knew. It dawned on her that he knew what she was going to do.

Lydia stood on the top step of the train carriage. The heavy door hung open but she knew better than to attempt to descend to the platform below. The rain gusted into her face as she leaned against the doorframe, looking out with an unhurried gaze and wishing she smoked. Leaning and smoking went together, they made a person appear unthreatening. And more than anything right now she wanted to appear unthreatening.

Three soldiers were busy offloading a string of men from the baggage wagon at the far end of the train. Lydia watched them. The men were prisoners. She could see it in their hunched shoulders and tight pale faces, in the way they moved, as if expecting a blow. Some wore coats, several in suits, collars turned up against the rain; one in nothing more than shirt sleeves. All were bare-headed.

She made herself study them carefully, refusing to look away however much she wanted to. It felt too intimate. There was a nakedness about the hunched figures, their fear and degradation too huge and too exposed for everyone to see. It sickened her stomach.

Papa, is this what it’s like for you? This kind of humiliation?

It was hard to keep her mouth closed, to jam the words inside. She could tell by their clothes and their air of bewilderment that these men must be new prisoners. It showed in their nervous glances at the guards, even in the way one of them looked for a brief moment at Lydia herself. The shame in the eyes. One man with a small bundle wrapped in a scarf under his arm managed an odd little smile at Lydia, fighting to pretend this was all a hideous mistake. That they’d been snatched from warm beds for… what? The dropping of an unwary word, the voicing of a wrong thought?

Using rifles like cattle prods, the three soldiers were herding them into a long line that stumbled towards the station entrance. At the very back a small plump man started sobbing in a loud outpouring of grief. To Lydia it sounded more like a sick animal than a human being.

‘Get back inside.’

It was a guard patrolling the platform. He jabbed at the open carriage door to slam it shut.

‘Comrade soldat.’ Lydia smiled at him and pulled off her hat, letting her hair fall loose. He was young. He smiled back.

‘My lungs aren’t good,’ she said, ‘and there’s always smoke in my compartment. I need some clean air.’ She inhaled noisily to emphasise the point and felt the sleet nip at the back of her throat. It made her cough.

‘Well shut the door and open its window instead.’ His tone was friendly.

At that moment she spotted an elegant figure descending the steps further along the train. It was Antonina. She ducked her head against the rain that glistened on her furs like a shower of diamonds. Behind her the two uniformed companions were wrestling her luggage off the train, but Alexei had been wrong about her. She didn’t hurry. She took her time. She smoothed her soft grey leather gloves over her fingers, adjusted the angle of her hat, then with expressionless eyes she studied the wretched line of prisoners. She murmured something to one of the uniforms and instantly a small black umbrella was produced for her. She accepted it but held it too high above her head, indifferent to the sleet streaming in under it.

Lydia took a deep breath. She had a few brief seconds, a minute at most. No longer, before the train moved on. The soldier had his hand on the door, ready to slam it shut.

‘Antonina!’ she called.

The pair of deep-set eyes turned towards her, narrowed against the rain, and she gave a faint nod of recognition.

The soldier started to shut the carriage door. ‘Move back there.’

Lydia didn’t move. ‘Antonina,’ she called again.

With neat unhurried steps, the dove-grey boots crossed the wet platform and Antonina stood in front of her, appearing small from Lydia’s view high up on the steps of the train. The soldier moved away instantly with a smart salute. Clearly he knew who this woman was. In her furs and her carmine lipstick she looked much less approachable than in her burgundy dressing gown.

Lydia tried a friendly smile but the only response was a distant little grimace.

‘Before you even ask, young comrade,’ the woman said briskly, ‘the answer is no.’

‘The answer to what?’

‘To your question.’

‘I haven’t asked a question.’

‘But you were going to.’

Lydia said nothing.

‘Weren’t you?’ Antonina tipped back her umbrella and gave Lydia a long scrutiny, her beautifully groomed eyebrows arching into a mocking curve. ‘Yes, I can see you were.’

Her manner rattled Lydia. It was dismissive, it made her feel clumsy and childish. She wasn’t sure of her footing any more. There was something so sleek and slippery about this woman today that Lydia could feel herself sliding off with nothing to hold on to.

‘I just wanted to say goodbye,’ she murmured.

‘Do svidania, comrade.’

‘And…’

‘And what?’

‘And yes,… you are right. I want to ask something.’

‘Everyone always wants to ask me for something.’ Her dark gaze slid off to where the prisoners on the platform had bunched up, awaiting further orders. Their hair was plastered to their heads by the incessant rain and the man who had been sobbing noisily was quiet now, his face in his hands, his shoulders trembling.

Lydia looked away this time. It was too much.

‘Everyone,’ Antonina continued in a voice that sounded amused, though her eyes were sad and serious, ‘wants me to convey a parcel, to pass on a message, to beg my husband, the Commandant, for this or that for their loved one.’

Lydia shifted uneasily on the steps. ‘Mistakes are sometimes made,’ she said. ‘Not everyone is guilty.’

The woman gave a short hard laugh. ‘The OGPU decisions are always right.’

Time was running out.

Lydia said quickly, ‘I am searching for someone.’

‘Isn’t everybody?’

‘His name is Jens Friis. He was captured in 1917 but he shouldn’t be in a Russian prison at all because he’s Danish. I just need to know if he’s here in this camp. That’s all. Nothing more. To hear that…’

The woman’s eyes turned to her, smooth and cold as black ice, but the palms of her pale leather gloves were fretting against each other fiercely. She noticed the way Lydia glanced at them and for the first time she smiled, a small, angry smile, but still a smile.

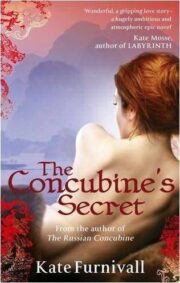

"The Concubine’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Concubine’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Concubine’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.