For a moment, I gape with everyone else, my trauma forgotten. Bedecked in gold, the Devi is strikingly visible, yet tiny. I think she holds lotuses in her hand, but it’s too far to be sure. What I can make out, even at this distance, is that she has four arms—though she engages only the lower pair to wave to her audience. Revolving smoothly like a trinket on a turntable, she bestows benevolence in each direction equally.

“Welcome,” she says, and the throngs roar in response. “I’m so gratified you have come to see me.” Her face is a bright, shining gold, her voice sweet and reassuring even through the distortion of the loudspeakers. “Do you know the one cure for all the unhappiness in this world, for all the fear and strife you have seen?”

“Devi ma,” erupts the reply from the beach, so thunderous, so passionate, I feel like an interloper for not joining in myself. Waiting for the response to subside, the Devi continues to rotate silently.

“What has brought you here today?” she asks, and begins to list the war, the bomb, all the other dangers the audience faces. “Dark forces are at work against your Devi ma, people who do not believe in me.” She urges the crowd, in the same honeyed voice, to flush out her enemies and exterminate them without mercy. “Nourish the land with their blood, just like seawater nourishes the beach.”

Bursts of acclamation continue to rise from the crowd. She negotiates them perfectly, as if she has premeasured the seconds required for each pause, programmed them into her speech. Her tone never varies too much—she remains equable, immune to the fervor of her admirers’ outpourings. “I am your protector, your savior. Once your feet have touched these sands, I will forever keep you safe under my shield.”

At the end of her speech, the volume of her voice increases sharply. “To all my charges, to all my beloved children, Devi ma just says, Come to me.”

The crowd surges towards the hotel, a few figures even manage to clamber some feet up the tower that bears the turret. The Devi extends her lower arms in benediction and sparks begin to drizzle from her fingertips. Her body rises—almost imperceptibly at first, and then in a more visible corkscrew motion, until she levitates, still rotating, several feet above the turret. The drizzles turn into showers, drops of fire begin cascading from her feet as well. I strain to make out a rope or other support, but can’t. She coruscates in the air, like a comet or shooting star, magically pinned mid-flight.

Fireworks burst forth again from the terrace. This time, the night blooms not only with their flashes, but also with the white parachutes released by exploding rockets. Thousands of heads turn up to watch the armada’s floating descent—hands point excitedly at the lit Devi idols dangling at each parachute’s end. The struggle to snag the figurines gets so frenzied that the airdrop might have been engineered from heaven by god herself. By the time the smoke clears, the Devi has vaporized. The beach roils with excitement for a few more moments, after which the audience settles down to await her next appearance.

“At least we have a destination now,” Jaz says, as I stare at the still-smoking terraces, unable to pull my gaze away. Could this be some sort of divine coincidence? The Devi appearing at the very hotel where Karun and I got married? I try to tamp down the irrational optimism billowing up inside. All I need do is make it to our bridal suite, and Karun will be still reclining on our wedding bed, the Buddha looking down benevolently.

My exuberance is short-lived. Sighting the Devi is very different from actually getting to her. The crowd remains as impenetrable as toffee, slurping around to pull us back each time we discover a new foothold. Jaz has an idea: “Perhaps we should try capitalizing on your sari.”

He starts announcing I am Devi ma’s helper, who needs to reach the Indica urgently. Unfortunately, the enthrallment over my sari has dissipated, people seem quite blasé about my glow after witnessing the Devi’s pyrotechnics. A woman stands stoutly in my path, observing me as she might an insect struggling in a web. “Where do you think you’re going?”

“Please. I need to get through. To see Devi ma.”

“And what do you suppose the rest of us have gathered here for? To enjoy the sea breeze? To eat bhel puri? You’re not the only one who wants her blessing.”

“You don’t understand—”

“I understand perfectly. We’re not villagers that you can dazzle us by wearing something bright and shiny. Let’s see how you get past.” In short order, she’s organized a clutch of onlookers, arms crossed, to blockade me.

The night turns darker. “We’ll be stuck here forever,” I whisper, and Jaz can only offer a ratifying silence. I stare at the Indica in the distance—its turrets now give it the appearance of a fortress, one ensconcing an impregnable bridal suite. The thought that all my effort has been for naught, that Karun may finally be so close, and yet so excruciatingly unreachable, fills me with hopelessness. A pinpoint of light, perhaps the last floating ember from the spent fireworks, hovers hazily in the air. I turn away, unable to bear to see it extinguished.

When I look back, the speck, rather than dying out, has grown, both in brightness and size. I track its path in fascination as it homes in—could it be a firefly attracted to my sari? Except it soon gets too big to be a firefly, looking more like a seated form floating through the darkness—someone on a flying carpet, perhaps. It draws closer, and I begin to hear bells, then feel underfoot vibrations, then discern large auricular outlines that emerge from the dark to flap into life. And finally the recognizable figure, surely an apparition born of my desperation, aglow in a sari similar to mine.

“Didi, up here,” the voice calls, as the fat woman screams and her cohorts blocking my path scramble for safety. Astride the giant pachyderm lurching towards us is Guddi.

12

THE ELEPHANT IS BETTER THAN AN AIRBORNE CHARIOT, an enchanted galleon. As we bob and pitch across the beach, the sea of humanity parts before us in waves. “It’s the only way to get through such a crowd,” Guddi says. “At first I was terrified we’d trample someone. But then I realized people always find the space to squeeze away somehow. Just like insects. Isn’t that right, Shyamu?” She reaches forward and pats the elephant’s head. “Except for that one lady this afternoon. Don’t feel guilty, Shyamu, it’s not your fault. She was quite old, anyway—how long could she have lived?”

Guddi starts chattering about her adventures since we last saw her, about the journey on the other side of the tracks that brought her and Anupam to safety at the Indica the night before. “All thanks to Vivek bhaiyya. The train driver’s helper—did you meet him? He took us crawling over this big-big pipe—so big we could have probably walked through, at least Anupam and me. But Bhaiyya said it would be very dirty inside—all the kaka and susu from the city—chhi! And we had to remain completely silent—otherwise, Bhaiyya said, we’d all end up like Madhu didi.” She stops and bites her lip. “I don’t suppose there’s any chance… ?” I shake my head, and she starts crying. “I miss her. And Mura chacha. I wish they were here with us, Didi.”

In a few moments, though, she’s cheery again. “I couldn’t believe it when I saw that glow—I’d been searching the crowd all evening, praying to Devi ma with all my might. Did I tell you, Didi, they’re taking me to see her in person tonight? Anyway, Shyamu didn’t want to investigate, but I insisted—I told him the light had to be from a sari just like mine—either yours or Madhu didi’s. See, Shyamu? I was right. One has to have faith—even elephants should pray once in a while. To Ganesh, if they like—I’m sure Devi ma wouldn’t get jealous if they also asked her blessing on the side.

“You should have seen how amazed the hotel people were when I told them I sat on my first elephant at nine. That we had a whole family in our village, whom we rode all the time. That’s why they let me have Shyamu—do you think they would’ve trusted me otherwise? Sometimes I feel I must have been an elephant myself in a previous life. I knew the instant we locked eyes that we were soul mates—Shyamu, isn’t that right?” She strokes his head, but he takes no notice. “Too bad Anupam wasn’t as lucky—she’d never even sat on an elephant before, so she’s stuck in the hotel kitchen, poor thing. She’ll be thrilled to see you, if she ever finishes all the chores they’re probably loading her with. But tell me, Didi, how did you escape? You and…” She gazes quickly at Jaz, unsure how to address him. “You and Bhaiyya.”

I begin to call Jaz by his name, then catch myself. “Gaurav bhaiyya. Remember, he was the person from the second compartment when the train derailed? He’s a friend of Mura chacha. We came through Mahim, not over the pipe like you did. Without him, I never would have made it.”

Guddi’s eyes widen. “Mahim? Isn’t that where all the Muslims live? Don’t they do terrible things to virgins?”

“Yes, they eat them,” Jaz says, and Guddi recoils in horror.

Our ride atop Shyamu isn’t the most comfortable. He doesn’t have a proper howdah, just a thick blanket that’s strapped on, resulting in the constant danger of falling off. Guddi tugs his ears to make him turn right or left, and digs her knuckles into his neck to make him start or halt (her maneuvers succeed only part of the time). “Stop that, Shyamu,” she admonishes, upon hearing my startled cry as the tip of his trunk starts rummaging around in my lap. “Don’t mind him—he’s just looking for the flowers.” She pushes forward the basket of petals for him to dip into. At the end of each stop, she loops his trunk around another basket, this one empty, to collect offerings for the Devi. Fruits, garlands, currency notes, even a few wristwatches and necklaces, pour in with each haul. Most of the bananas disappear into Shyamu’s mouth, along with the odd piece of jewelry. “Look what someone put in!” Guddi exclaims, holding up a cell phone. “They don’t work anymore, so Devi ma has said we can keep these.”

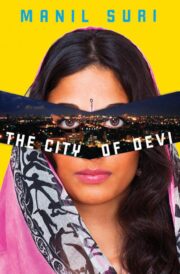

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.