“You’re right. It was a mistake.” He shot up from the couch and headed to the door. This time, I’d left the key in the lock, and he was able to open it.

“Be sure to give Sarita my best,” I yelled, as he slammed the door behind himself.

THE ZURICH DIRTY BOMB attacks occurred on September 11, four days before my family’s departure to Switzerland. Explosions along the Bahnhofstrasse and at the university hospital left large swathes of the city uninhabitable. Similar strikes followed later that day in New York, London, Rome, Toronto, and Frankfurt. As if the choice of date weren’t incriminating enough, jihadi literature turned up near two of the bomb sites, and a video claiming responsibility, by a new Al Qaeda-like group, appeared on the internet.

Those anticipating the next big terrorist incident for the past several years may have sighed with relief that it had finally occurred. They might have pointed out that despite widespread panic and disruption, the damage didn’t approach that caused by a single thermonuclear explosion. But the real destruction in this case, illustrating just how much this September 11 heir had evolved over its parent, came with the ensuing cyber attacks. The dirty bombs were merely the gunshot starting the race, signaling hackers with fingers poised over keyboards to launch their malware.

Five weeks later, the Jazter still marvels at how quick and easy it was to unravel the order of the entire world. First came the news hoaxes, saturating the internet, whipping up the panic already frothing in place. A fake suicide truck attack on the hastily called NATO summit in Brussels was so convincingly reported that even CNN listed the names of heads of state supposedly felled. Warnings of an imminent electromagnetic pulse over the U.S. touched off hysterical runs on banks all the way down to Mexico and Belize. Meanwhile, the armies of cyber bugs on the loose found crevices to crawl through even the most impregnable firewalls. They invaded enough strategic nodes and sources to wrest control of the entire global news network.

Perhaps this was the greatest genius of the cyber jihadis: the monopoly they clinched on information. They realized how helplessly addicted the population had become to knowing in this information age. So what if news was tainted or unreliable?—people needed their daily fix. They would gladly swallow the most improbable rumors, the most outlandish fabrications, to quell the ravenousness within. Even the Jazter, always a voracious consumer of news, succumbed to this junk food urge.

Not that some of these inconceivable scenarios didn’t turn out to be true. The viruses had gained cunning by now, learned to down bigger game. They sabotaged power stations and exploded gas lines, bewitched airliners over the Atlantic into executing suicide dives. People could no longer separate reality from fabrication, trust the ground they walked on, the world they lived in. Did Morocco actually invade Spain? Did a string of reactors really blow up in France? The actual answers mattered less and less, as panic (and despondency) increased.

But harking back to the early days right after September 11, the one irrefutable fact was that Switzerland immediately rescinded my family’s visas. Their government pushed through an emergency law overnight, banning all Muslim visitors. My father scrambled to find another country that would accept us, but similar bills popped all over, effectively shuttering the West. The only options that remained were Islamic states, particularly those in the Gulf.

My parents already had tourist visas for Dubai, so that seemed the most promising choice. Unfortunately, well-heeled Muslims trying to escape India mobbed every consulate in Bombay (even the one for Pakistan, essentially manned only by the watchman ever since the ambassador fled). My father pulled every string he could to get my passport stamped, but the Dubai embassy informed him there would be a six-month wait.

With time of the essence, and Dubai only a temporary destination, we realized the only practical solution was for my parents to go ahead without me. From there, they could more effectively lobby other Arab states for a permanent haven, and get me a visa directly to that country. The UAE itself seemed promising, since my parents had lectured in several of the emirates after the democracy rumblings generated by the Tunisian revolution. The Saudis might also be interested, having recently offered them both university positions. (Akbar’s underlying tenet of a divine right to power had appeared particularly attractive ever since the Arab Spring.)

All of this looked quite bleak for the Jazter. Beggars can’t be choosers, but surely some alternative to the rampant repression against his ilk practiced in these places had to exist? Even if shikar was popular among Arabs as reports claimed, Riyadh or Sharjah weren’t exactly high on my list. I tried to find consolation in the reports that, compared to Iran, the Saudis had probably beheaded fewer gays.

Since I would be staying behind, I needed a safer place. Fortunately, we managed to exchange apartments just two days before my parents left. The new residence was located in the Muslim quarter behind Crawford Market—a shabby flat, old and crumbling, with a shared pair of toilets at the end of the outside corridor. But the place was secure—or at least relatively so, compared to our previous address.

The day before I accompanied them to Ballard Pier to catch their ship, I found my father sitting on the floor of one of the musty rooms, his books and prayer scroll collection spread out around him. I recognized the well-worn Koran by Nafi that he still pored over for hours. “See this?” he asked, holding up a copy of An Emperor’s Bequest to Islam. “It’s from the first edition—they only published five hundred of them—that’s all they expected to sell. Your mother and I worked on it for eight years—this is the original copy the publisher sent us in the mail from New York.” He opened it to the dedication page, to the inscription I’d read many times before—“May the light always shine on our son, Ijaz.” “The only thing more thrilling to hold in my hands for the first time was your tiny body, just after you were born.”

He closed the book and laid it down on the floor. “We always hoped you’d accept our gift to you, Ijaz. When you spurned it, when you showed such disdain for religion, we understood, of course. What child hasn’t experienced the need to rebel? But we felt so sad. Not because we’d lost a follower, but because you’d never see the beauty we had. All the wisdom contained in these texts, the answers to so many problems ripping us apart now.” He caressed the cover of an old textbook on comparative religions, then ran his fingers over the ornate Urdu letters on one of the scrolls. The dusty light shone around his head like rays from God.

When he looked up, though, his face was haggard. “They’ve won, Ijaz. I don’t know what we’ll do. They’ve finally taken over Islam—hijacked it completely with their threats and bombs. All our work, all our effort, all our credibility—all lost. We have to go on trying, of course, but with everything that’s happened, who’ll believe us now?” I shifted uncomfortably, unable to think of words of comfort.

“You know what makes me the most ashamed? Having to leave you in this state. Not knowing if we’ll ever see you again. I never thought I’d be the type to abandon my own son.”

“I’ll be fine. No need to worry, it’s probably only a matter of a month.”

He shook his head. “That’s been the problem, all along. We’ve never worried about you enough. Right from Switzerland, we’ve always left you to find your own path. You might have thought us disinterested, but our fault has been to trust you too much. Not interfering in your life, not asking what you liked, what you loved—we simply took it too far.” He held out his hand, and I put my palm in his. Had we enjoyed a different relationship, we might have hugged.

“Take the physicist, for instance. We could have done so much more to encourage you on. Such a sincere boy, so smart, such a relief to see you bring him home again after all these years. I told your mother we had to give you your privacy. We thought we’d stroll around while the two of you were in the apartment, but the blackout made it impossible. We ended up drinking six cups of tea at that tiny café near Lotus.”

“I had no idea—”

“I hope you’ll see more of him once we leave. Tell the neighbors he’s your cousin—it’ll be much safer with two people living here rather than just one. Plus, your mother and I will feel much better knowing you’re with someone so close.”

“But how did you know?”

My father seemed genuinely confused. “How did I know what?”

CHAOS REIGNED at the docks, the multitudes clamoring to get on the old freighter of such biblical proportions that they might have just learnt of the Great Flood. My father’s contacts had managed to procure two of the last tickets out for him, and moreover, avoid the trap of air travel which had essentially ground to a halt. Right up to the moment my parents entered the processing booth, people were offering them lakhs of rupees to buy their slots. I waited around afterwards, but couldn’t spot them in the crowd surging up the gangplank.

Watching the ship launch into the churning grey sea, I realized my odds of ever seeing my parents again were small. The Jazter would probably never succeed in migrating, never have to test Arabia’s tolerance for shikar. Back at the apartment, I could still hear my father’s words ring in my ears—get Karun to move in, live with someone I loved (I’d decided that’s what he meant after all). We could always find somewhere in the countryside to take cover, should the city situation deteriorate too much.

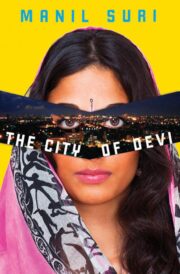

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.