Rahim whistles. “Tell me.”

So the Jazter relates his tale. Rahim is misty-eyed afterwards. “All my life, I’ve waited to care like that for someone. And have him care as much for me.” He smiles ruefully. “I suppose you didn’t know your auntie was so sentimental, such a helpless romantic at heart.”

He tells me the best option might be to take Cadell Road, the main street past the mosque. “They’re going to be on the lookout for you, no matter how I try to throw them off. But it’s bound to be an entertainment night if they’ve captured prisoners from the train—so you might be able to slip through amidst the crowds surging towards the mosque.” He folds my fingers around a roll of money. “The causeway to Bandra is probably too dangerous—you might have to find a boat across. Either way, it’s going to cost.”

“And you won’t get into trouble?”

“With the Limbus? They’re too stupid to figure anything out. And my boss isn’t here, so he’ll never know.”

We hug, and I glimpse an expression of guileless affection on Rahim’s face which takes me back many years. Or perhaps it’s just the light from the table lamp, catching him in such a way to make him look very young. “I hope you find him,” he says.

As I step into the corridor to go get Sarita, he calls after me. “Actually, I did come close to caring a lot for somebody once. But I was only sixteen, and thought it was just a crush.”

INCREDIBLY, MY VISION did come true—Karun and the Jazter ended up living together in our own private flat. Not in Bombay, but Delhi. That’s where Karun returned when he graduated with his bachelor’s, to be closer to his mother, and also pursue a post-graduate degree. Since I received my bachelor of commerce at the same time, I said goodbye to my befuddled parents (“But Mumbai is the financial capital!”) and took up a job at an investment center in Connaught Place.

Our joint apartment almost didn’t come to pass, simply because nobody would rent us one. To head off any reservations, we’d prepared an explanation of wanting to share expenses to save money for when we married. But the sticking factor turned out to be religion rather than two men cohabiting. I’d heard of landlords in Bombay refusing to lease flats to Muslims, but they were ten times more bigoted in Delhi. (“All that terrorism, you know,” one explained rather kindly.) The question of Karun renting a place in his name didn’t arise, students being a category possibly even less welcome than Muslims.

For a while, we lived in a “barsati” in a Muslim section of Old Delhi. Coming from Bombay, I was not familiar with these single-room structures, built as servants’ quarters on house terraces. Ours came with a tiny toilet, a cubicle for bathing, and a hot plate (for which the landlord, Mr. Suleiman, charged us fifty rupees a month for the extra electricity). The place (our “penthouse,” as we called it) had the advantage of complete privacy—only the most determined intruders would climb four floors to barge in on a terrace that baked all day in the heat.

Still, for the two months we spent there, Karun (or rather Kasim, the Muslim name we made up to give Mr. Suleiman) and I were able to relax into the tranquillity of quotidian life for the first time. We made tea on the hot plate each morning and shared a packet of Gluco biscuits for breakfast (seven biscuits each, with an extra one sometimes, which we split in half). We left at around eight and returned only after sunset, trying out all the oily but inexpensive dhabbas in nearby markets. Sometimes, we went for a movie, but usually just watched television on the small portable set we’d smuggled up (so that Mr. Suleiman didn’t charge us even more for electricity). Once it cooled down enough, we had sex in the room, then dragged the charpoys outside to wherever the breeze seemed strongest that night. Karun liked bedtime stories, so I usually narrated a fairy tale we’d both heard as children. By the time I got to the middle, he fell asleep.

On very hot nights, I tried to cool us down by talking about all the snow I’d seen while growing up. The great blizzard of Chicago when we shivered without electricity for an entire week, the white-daubed houses and carpeted streets that turned Geneva into a postcard. The trees aglitter with ice under which I lay, the snow chairs I built to cozy up in, the frozen lakes across which I danced and skimmed. Karun, who had never experienced snow, snuggled closer, as if he could actually feel its chill. That’s when I told him the nearby Yamuna had frozen solid against its banks, that the roads downstairs were hushed and white, that the gleam of our rooftop came from snow, not moonlight. Once, I even taught him how to skate, as if the terrace outside our barsati had been converted into a giant ice rink.

I awoke every dawn when the birds just started chirping. I rolled into Karun’s bed—I enjoyed cuddling with him in the cool. Sometimes, I pressed and poked with my erection, or stroked his groin, or nibbled at his foreskin. I loved bothering him like that while he lay half asleep—he either groaned and turned away, or succumbed to my advances. Afterwards, he tried to catch a few more winks. I held him in my arms and waited for the sun to rise from behind the rooftops, to brush his skin with its first delicate strokes of golden light.

Perhaps our abode wasn’t as private as we imagined. Perhaps other residents stirred at the same time of dawn in their barsatis. One day, as I played with a still-drowsy Karun, a rock came hurtling onto our terrace from an adjacent rooftop. When I returned that evening, a knot of women who lived in the lower floors stood gossiping on the steps by the entrance. The way they went silent and stared as I passed made it clear they were talking about us. The next day, Mr. Suleiman braved the four floors to our barsati to order us to leave.

I HAD NOT WANTED to enlist my parents’ help in getting a flat, since I didn’t want them to know about Karun and me living together. But I needn’t have worried. When, after two weeks of filthy hotel rooms, I finally gave in, my father readily swallowed the story I’d concocted about wanting to save money. “That physics student—I remember him. It’s good to have friends with such diverse interests.”

He put me in touch with Mrs. Singh, a widowed friend of a colleague, who asked Karun and me to come directly to the Green Park flat she had for rent. She looked much younger than I’d expected—about fifty, perhaps. Although dressed in the observant white of a widow, I noticed her feet peeking out from under the cuffs of her salwaar astride exuberantly pink sandals. “I live right below, but you have your own private entrance. Mr. Singh had that installed just before he passed.” Her scrutiny alternated between Karun and me, as if trying to figure us out. “It’s only a one-bedroom, but it does have two beds.” She pointed them out—they looked as modest as the cots in Karun’s Bombay hostel. “I normally rent only to husband-and-wife couples—I had the mai pull them apart for you this morning and put the nightstand in between.” She locked gazes with me. “This is the way they should look when the mai comes in at ten every morning to clean.”

“I’m not sure I understand.”

“Look, Mr. Hassan. You’re telling me you and your friend want to save money. Fine. I didn’t ask, and I don’t care. You won’t find another Punjabi woman in all of Delhi who’s less inquisitive than Mrs. Singh. But I draw the line at gossip. I like my tenants to be quiet and clean. All I ask is you not give the mai any reason to start her tongue wagging.” She stared at each one of us in turn. “I can show you the kitchen if we’re agreed.”

The flat rented for half my salary, so it didn’t look like we’d be saving much money for our purported weddings. “Plus, I’ll need a year’s rent in advance as deposit,” Mrs. Singh said. “Which is pretty standard for Delhi.” I had to SOS my father for help again—fortunately, he agreed to wire me the money.

The next two years were the happiest in my life. I felt like the hero (sometimes the heroine) of one of the fairy tales I related to Karun every night. Swirling through flower-laden fields, galloping across magical plains—who cared if it was only Delhi’s congested lanes, as long as I had Karun by my side? We perfected the art of haggling, and learnt to tenderize even the toughest Delhi hen by marinating it in yoghurt overnight. We bought half the board games on the market, and several new accessories for my train set, indulging every whim our childhoods had denied. Rearranging the furniture for the mai each morning became a drag, so we learnt to squeeze together in the same bed. At night, we made love with barely a gasp or creak so as not to disturb Mrs. Singh.

Her demeanor softened soon after we moved in. She helped us fill out the application for a phone line and figure out the electricity bill. She gave us cucumbers from her vines on the terrace, and remembered to wish us well on both Muslim and Hindu holidays. Two months after we moved in, she sent up a large pot of chicken lentil soup when we both got the flu. Most endearing of all, she treated us as a couple—long before the shopkeepers downstairs fell into the habit from seeing us together so often. The bania advised us to start buying detergent in the family size to save money, the vegetable woman remembered I liked okra and Karun peas, the meatwalla saved us just enough chops for two persons to eat.

The only thorn in our side was Mrs. Singh’s eighteen-year-old son Harjeet. He scowled each time he encountered us on the steps, positioning his hefty frame to make it awkward to pass. He made raucously loud homophobic comments from the verandah when he got together with his Sikh friends. We stopped hanging out our clothes to dry on the terrace when gobs of dirt started mysteriously landing on them (underwear seemed especially vulnerable). He lifted weights in his turban and shorts on the landing outside our door on Sundays, so that he could mutter obscenities in case we accidentally glanced his way.

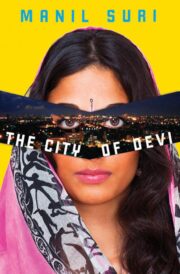

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.