Walking to the bus stop, I realized I’d become too fixated on Karun in the past few months. Release was release, with whomever one found it—that’s what the Jazter had always said. Hadn’t another wise man, the Buddha himself, warned about the evils of attachment?

So I spent the next few days frequenting old haunts again—the alleys near the Gateway, the facilities at Bandra, even the Oval in the rain. I rode the “gandu car,” the notorious last compartment named after all the backdoor action it saw, on late-night suburban trains. I got lucky with a cashier wearing a McDonald’s uniform in the sparkling tiled toilet of a newly opened shopping mall. But as I entered him, as my body heaved and strained, I found myself conjuring up Karun’s face. Guilt flooded in—as if I’d been unfaithful, as if I’d strayed.

It became an aversion therapy program, the way this guilt tainted every encounter. My favorite pastime lost its luster—the chase no longer thrilling, the prey too coarse, too anonymous, too un-Karun-like. How could this have happened? I felt like railing. Such crippling fallout from just a few innocent months of dating?

“You look completely lovelorn,” Rahim declared at his party, after admonishing me for not having kept in better touch. “Will I have to torture it out of you or will you tell me who he is?” He had developed a sashay to his walk—more matronly than nubile, and discovered mascara to somewhat alarming results. “Mum’s the word, I see—but that’s OK since I have a number of people here who’ll make my little Jazmine forget him.”

The “wedding” involved Rahim’s friend Akbar, who appeared in ceremonial drag—a red sari complete with ankle bracelets adorned with tiny bells. “She believes in married life, just to a different husband each month,” Rahim explained. “She’s tired of repeating the nikah, so tonight we’re going Hindu for a change.” Sure enough, the bride and groom (wearing the traditional headgear of jasmine buds) did their seven circles around a floor lamp representing the fire, after which Akbar swirled a platter with flowers and a lit oil lamp in ritual circles in front of his betrothed’s face. “Now kneel down and repeat them around the part that really counts,” Rahim instructed, and to hoots and claps, Akbar obeyed.

Afterwards, the crowd gave a collective yank on Akbar’s sari, unwinding it in a long swirl of fabric that sent him spinning across the room like a top. Watching Akbar prance around in his bikini briefs, I felt glad I hadn’t brought Karun—who by now would have probably stalked out. The game of musical laps that followed took forever to play because of all the poking it prompted, after which Rahim herded us into the study he had converted into a pitch-black back room. “This is the way to fight back the respectability drowning our poor deluded sisters in the West. Long live masti, long live mischievousness.”

Wisps of sunlight seeping around the papering on the windows woke me in the morning. I extricated myself from under the arm across my chest and got up from the floor—it took me a half hour to find my clothes. By the time I reached home, my mind pounded with the thought of Karun. I had not talked to him for days—what if I had let him slip away? I longed to coax out his smile again, yearned for his steadfastness—even his scientific prattle seemed so charming in retrospect. I had to see him despite the absence of fleshly prospects. Would I have to finally yield ground to his pontifications about life being more than sex?

Gathering up my courage, I dialed his number. “Where have you been? I’ve missed you,” he said.

BY SEPTEMBER, WITH THE RAIN still keeping us chaste, I wondered if the monsoons would ever end. Just as I prepared to splurge on a hotel room in desperation, my luck turned. My parents announced their departure for a week-long conference in Jakarta. I declined their invitation to come along, which puzzled them. “I suppose it should be OK with Nazir here to look after you.” I had to pay him the entire five hundred saved up for the hotel room to coax him into taking a vacation of his own.

I got down to the first order of business with Karun right away. I fucked him in every room of the flat, in my parents’ bed and on the kitchen floor. When he tired, I revived him with a bubble bath, then fucked him some more. He locked himself in the toilet, not emerging until I promised to stop. I made a good-faith effort to keep my hands (and other parts) off, but lasted only an hour. By the third day, though, even I was too sore.

Fortunately, we had college to attend. I came back at five, worried he might not return, wishing I hadn’t wielded my wicket to such excess. At six, the bell rang. Karun must have recovered as well, because when I herded him through my bedroom door, he didn’t protest.

Eventually, there arose the pesky problem of food. Nazir had demanded too much money for biryani this time, and we’d already devoured the refrigerator scraps down to the stalks of coriander. “I used to cook while my mother worked evenings,” Karun said, so we went shopping in the nearby outdoor market.

Except neither of us knew how to haggle. Vegetable hawkers saw us treading carefully through the monsoon muck in our sneakers and raised their prices two- and threefold. “I know your mother,” a fisherwoman purred. “She always buys pomfret here because she knows I never cheat.” Chicken sellers, egg grocers, even a samosa-vending tout, all smiled widely in welcome with the glint of rupee coins in their eyes.

“They can smell our inexperience. We need a strategy,” Karun said. “How about if I act willing to buy, and you pretend to pull me away because the price isn’t right?”

So I tried to channel my inner diva to play the shrewish wife. I accused the cauliflower seller of eating the good parts and trying to palm off the leaves, ordered Karun to return a bag of plums because they’d be all pit inside. I overplayed my role with the fish, voicing so many suspicions about its freshness that I provoked the fisherwoman into a fight. We fled to the chicken shop, trailed by a hail of curses in Marathi.

Unfortunately, the hen we bought remained tough even after three hours of cooking. Karun made various attempts to tenderize it—adding vinegar and yoghurt and pungent powders he found in the cabinets, even stabbing at the pieces in frustration with a knife. At midnight, I suggested we just dip bread into the gravy. Karun’s eyes widened as he tasted it. “I think I added too many chilies.”

“It’s nice,” I told him, trying not to choke. I discreetly got up and brought us some water. By the end of the meal, we were using chunks of raw cauliflower to buffer each bite.

“I can wash off the chilies and try again tomorrow,” Karun said. “I guess it’s been a while since I cooked.”

He looked so dejected that I pulled him to myself, nestling him between my thighs. I buried my nose into his hair to identify the different curry spices, like one might the bouquet components of a fine wine. His fingers smelled mostly of garlic and ginger—kissing them, I noticed the tips stained yellow with turmeric. “It’s fine. I enjoyed our little chemistry experiment. Plus it was fun going shopping.” I put my arms around his chest and rocked him from side to side.

Sitting there, with Karun in my lap, I caught a glimpse of a future I could never have imagined. Karun and the Jazter, snug and domesticated like this, rocking gently through life. I almost burst out laughing, but then stopped. Was the picture so corny, so absurd, so completely removed from the realm of possibility? What future did the Jazter see for himself, exactly? Would his days of shikar continue indefinitely, or did he dare look beyond the beaches and the train stations and the alleys? Could he, in some part buried deep within, secretly crave conventionality? (Or was that too much of a heresy?)

I kissed Karun’s neck. The future, as always, felt too abstract to worry about, too nebulous, too otherworldly. What mattered was the here and now. The feel of Karun’s body as he reclined against me, the spices perfuming his hair and resting in their jars in the kitchen, the defiant chicken on the counter waiting to be subdued some more in the morning. I felt grateful for each magical moment we’d spent playing house together, grateful for the four days we still had left.

9

AS YUSUF SLIPS INTO THE DARKNESS OF MAHIM, I TRY TO PREPARE Sarita for meeting my cousin. “He owned an enormous flat at Chowpatty which he sold to buy this hotel. You might find him a bit—um—unusual.”

Rahim opens the door himself, and shrieks upon recognizing me. “My sweetie. My little Jazmine. What a surprise. After all this time, you’ve finally remembered your Auntie Rahim.” I’m unprepared for how rotund he’s become in the decade or so since I last laid eyes on him. His cheeks have acquired an unworldly ruddiness, his lips an ethereal gloss; his mascara addiction, so startling at the party at his house all those years ago, seems decidedly out of control. Could this have really been my first heartthrob, the one who presided over the Jazter’s mizuage ceremony, plucked the virginity diamond from his nose? Although thinking back, it really was more the other way round.

“Well don’t just stand there, come to me.” He wears so much attar that fumes rise from my shirt after we hug. I finesse my lips out of the way as he tries to kiss me. “Oh, you’re shy because we’re not alone.”

Sarita watches transfixed—somewhat worrisome, since this is hardly the place to pick up her sorely needed makeup tips. “And what gorgeous creature do we have here? All dressed up as a bride for the Pandvas, no less.” Rahim theatrically undrapes the sari edge from her head and sharply intakes his breath. “Naughty, naughty! The leopard’s a bit full-grown, isn’t he, to be changing from spots to stripes? Or should I say from meat to fish?” He cackles noisily.

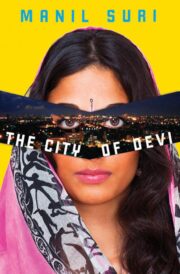

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.