I unwrap the pomegranate from my dupatta. I picture its juice beading on Karun’s lips. His tongue wiping it off, tasting the sweet and the sour, leaving behind a thin trace of the red. Doubt clutches at me again. To believe in folly like this, such desperation, such old wives’ tales. And yet all I need, I remind myself, is for him to remember those nights we played this game. I squeeze the pomegranate for reassurance, feel the smoothness of its skin. What made him leave so abruptly, in such an agitated state? Was it me from whom he was trying to get away? Will I ever see him again—all the disasters that could have befallen him in the eighteen days since?

I calm myself by imagining the spell taking effect. He stretches in bed, his shirt pulls up, and I notice its shadow against his skin. I pull it up higher and kiss his navel, pull it to his neck and kiss his clavicle, then rest my chin on his chest and lose myself somewhere along the line that separates his lips.

IT WAS THIS LINE that first drew me in. Not the eyes or the nose or the actual lips themselves but rather the way they rested against each other. What did the darkness between them signify? A hint of mystery? A mark of shyness? I felt an invitation there to explore what lay beyond his face, a promise of empathy I had not sensed in the scores of photographs I had evaluated over the years.

Of course I expertly scanned the other parts of the photo as well. I made sure his ears were both the same size and examined his hair for flecks of gray. I searched for scars and blemishes and found one on his chin. (A fall from a swing, perhaps—was he a daredevil still?) His eyes were set a little close together, but I didn’t find the effect unappealing. He looked like a boy posing in a childhood photograph, staring just past the camera at someone for reassurance—his mother, perhaps.

I kept being pulled back to the curve. The way it rose from the corner of his mouth to outline the innocence of each lip. The way it darkened intriguingly at its midpoint before continuing on its path, as graceful and symmetric as a mathematical plot. How did it change through the course of a day? Did it widen when he laughed, twist when he was angry, smudge when he was sad? What effect would desire have on it?

“Not bad, is he?” my sister Uma said, taking the photograph from my hand. “But let me warn you right away—he’s a scientist just like Anoop and the rest of them, and you know how those people are.” She rolled her eyes at me, though I knew she was fairly satisfied with my brother-in-law to whom she had been married three years. “Though you, with your statistics, should be able to better relate.”

I took the photograph back from her. A scientist, I thought, and imagined Karun with test tubes and microscopes, with banks of computer lights blinking in the background. Only the sheen of filing cabinets glimmered behind him in the picture. “So, do we have a fourth person for the picnic?” Uma inquired.

“Why ask me?” I replied. She could tell I was intrigued. “He’s Anoop’s friend—let him be the one to decide.”

Uma smiled meaningfully at my mother, who sighed. She believed in old-fashioned visits by the boy to the girl’s house, not these sorts of informal meetings. She had objected in the beginning, when Uma started setting up picnics and restaurant outings and once even a movie with two male colleagues. But we had already tried more formal routes without any success. The networking, the astrologers, the classified ads, all these had failed. I had approved at least a half dozen boys and came close to matrimony on three separate occasions, but a last-minute problem always intervened. The most recent match was the worst, almost permanently killing my chances: the boy’s grandfather passed away just before the wedding and his family declared me inauspicious, blaming the death on me. “Who knows how long our Bunty would have survived in her shadow?” they went around saying.

Last month I turned thirty-one (though prospective matches were told twenty-eight). In a few weeks I would complete my M.A. in statistics (my second master’s—I already had one in management sciences). With this latest degree, I would be not only old but also over-educated, my prospects slimmer still. My mother knew she had no choice but to agree to events like this picnic—her fear was that I might embark on yet another degree, immure myself permanently in the nunnery of college. “Do you even know what kind of family he comes from?” she asked worriedly.

“We’re just meeting him for a picnic, not digging up his ancestral tree,” Uma replied. “He’ll be here next Sunday—if you’re so worried, you can ask him yourself.”

I suspected that my sister had started arranging these meetings partly out of guilt. Being younger than me by three years made it all the more awkward that I remained unmarried. “Sarita’s been so busy exercising her brain that she hasn’t had time for her heart, the poor thing,” my mother would offer embarrassedly, by way of explanation. Except I think she had it backwards, that I buried myself in books precisely because of my lack of popularity, of romantic success. Ever since childhood, I’d been burdened with the epithet of the brainy one—perhaps I would have gladly cast off this reputation had more opportunities for fun come my way. I sometimes wished I enjoyed schoolwork less—like Uma, for instance, whose circle of friends seemed to widen each time her class rank dipped. Even my mother and she bonded over their shared phobia of algebra in ways I never could.

By the time I finished my bachelor’s in statistics, I had experienced the first inklings of how lonely a future might be lying in wait. “Numbers are her friends,” everyone kept repeating, as if I shrank from the prospect of two-legged company. I applied for the management master’s on a lark—with only twenty students selected nationwide, the scholarship offer caught me by surprise when it came. Could this be a solution? A way to break free of the shell I’d been pigeonholed in, to enter a field that depended on human interaction as its very basis? With the added remunerative promise of participating in the great Indian economic boom, surely this was an opportunity too good to miss?

It didn’t work out. The classes were interesting enough, with various simulations and case studies and theoretical management games I excelled in. But putting these lessons into practice at my textile factory internship afterwards proved disastrous. Both the workers and their supervisors instantly pegged me as a pushover—a walking, breathing catalogue of weaknesses meant to be exploited, ruthlessly and at will. The labor union leaders kept threatening to strike, the personnel staff walked out regularly over claimed slights, and an income tax official closed the place down without notice (it turned out he hadn’t been bribed). I fled at the end of my fourth week, never to use my degree again.

Statistics, when I returned for a master’s, was as orderly as before, as tranquil and welcoming. But I kept yearning for something more—I could not be sustained just by my love of the discipline. I envied the most driven of my classmates, the ones whose eyes lit up with compulsive interest at the very mention of Bayesian theory, who launched into animated lunchtime discussions of unbiased estimators and Markov chains. Why wasn’t I as possessed as they were? Why didn’t I share their obsessive desire to blaze a fiery career path across the subject’s firmament? Why did I keep mooning over such mundane distractions as falling in love or getting married?

Uma diagnosed my quandary as part of a larger problem. I was too content to let things flow, not resolute enough in any goal. “This is the twenty-first century—you have to know what you want, then set upon it with everything you’ve got.” I suppose she meant to offer herself as example—the way she aggressively pursued Anoop at college, then flaunted him as her boyfriend for four long years before finally marrying him (much to the relief of our parents). We both knew, however, that this model simply didn’t fit me. Despite the same underlying proportions to our facial features and body geometry (as far as I could determine), I felt neither as attractive as Uma nor as self-confident. Wasn’t this the very reason why I’d tacitly entrusted to my parents the task of fixing me up, of curing the solitude that had started shadowing me?

My sister phoned me the night before the picnic. “You’ll like Karun, I think. Just a hunch married people have.”

He appeared at our house at ten a.m. He was wearing black sandals, khaki pants, and a shirt of blue cotton. I did not look at him as he said hello, despite Uma’s call for assertiveness. Instead, I stared at the ground as I always did on such occasions, studying the guavas and parrots painted in green on the vestibule tiles around his feet.

I did let my gaze stray. Past the leather loop encircling his big toe, where I noticed the trimness of the nail and wondered if he had (like me) pared it the night before. Up the tiny hairs on the rise of his foot, ending just before the cloth of his trousers began. One cuff somehow caught high upon itself, so that the ankle (which I noticed was hairless) lay exposed. I did not let my eyes rise further, though Uma had teased me about his tireless legs and muscular thighs, about the strength that surely lay hidden in between.

It was his lips, the way they parted, that I wanted to examine. I looked once or twice towards his mouth but his face was averted each time. I saw the navy-colored emblem of a man riding a horse on his breast pocket. He was not well-built, not like the film heroes who bared their bodies in posters around town. But his chest rose and fell appealingly as he breathed, and I thought he looked healthy. The shirt, I decided, was American (though Uma claimed later it was a knockoff).

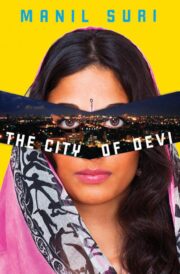

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.