I run up to Sarita. For some reason, she’s changed into a bridal costume since I last saw her—the lead of her sari unfurls in a flaming red swathe around her feet. “Come, we have to get out of here.” She just stares at me when I offer her my hand—I notice the line of white dots decorating her forehead. “We don’t have any time.” Something flickers in her eyes, and I wonder if she’s placed me. “It’s Gaurav. From the hospital. And the aquarium. Remember?”

“Gaurav? What happened?”

“The train derailed. Probably an ambush. We have to run.”

“But how did you find me?”

“I’ll explain everything. Just come with me.” I can see the confusion on her face begin to harden into suspicion, so I squat down beside her. “I know you told me not to follow, but I did—I jumped into the rear compartment when I saw you get on. I still want to save your life, do the same thing you did for me. But we have to leave immediately, since whoever made the train derail will show up any minute.”

“I… I don’t think. The girls. I can’t leave them here.”

So we try to get the girls to come with us, but they’re reluctant. “Mura chacha’s still inside,” the one half stuck in the train says. Her name is Madhu, and despite her sandwiched state, she seems in charge. “Can you go in and free him? Then we can all go visit Devi ma.”

Sarita declares she wants to search the wreckage as well—not for this Mura character, but for a pomegranate. I think I have not heard her correctly, but she starts babbling about how it’s the last pomegranate in all of Bombay and her very fate depends on it. I wonder if she has a concussion—is there a way to unobtrusively check her scalp? Madhu, meanwhile, barks orders at the other girls from her horizontal position. “Guddi, leave me alone and go fetch the train driver. Anupam, get this man here to help you lift the sleeper berth that fell on Mura chacha. You there. Go and help.”

She gets very irate when I reply there’s no time. “Mura chacha’s much more important than a few of your precious minutes. How can anyone be so selfish?”

I’m trying to drag Sarita away from the train as Madhu continues to hector me when there is a retort. “I’ve been shot,” Madhu screams, and holds up her hand. She has, indeed, been shot—blood streams down her arm and drips from her shoulder. More shots ring out, and she slumps forward, dangling limply from the waist. As the other girls scream, I grab Sarita’s hand and pull her behind the bogey to take cover. She stops jabbering about her pomegranate.

We scramble down a side street, Sarita’s sari blazing as conspicuously as a flag. The sounds of gunshots ricochet between the walls on either side. A few times, I think I hear someone running behind us. I lead Sarita in a zigzag through the labyrinth of an abandoned slum, finally stopping at a curbside bus shelter to catch my breath. For a moment, neither of us speaks as we gulp in air.

“Are they going to come looking for us?”

I shake my head. “My compartment was full of weapons. That’s probably what they were after.” As if to endorse my words, the rat-a-tat of a machine gun starts up. The sound is uncomfortably close, a little beyond the buildings we face—we must have circled around inadvertently.

Someone laughs, a man screams, and I hear more gunfire. The screaming resumes—its cadence is pitiful, pleading. “That sounds like Mura,” Sarita says. “Those shots—I wonder if Guddi and Anupam—” She looks at me, her lip bloodless.

Before I can offer her any reassurance, a motorcycle revs up. We hear it circle behind the buildings, then begin to get closer. “It’s coming down the street,” I say, grabbing Sarita’s hand and pulling her down behind the shelter wall. I peer cautiously over the edge after the motorcycle has passed, then duck again, as another motorcycle, then a van, come rumbling up behind. The cries are now coming from the van.

“It’s the Limbus,” I whisper. “They’re just like the hoodlums in khaki, only Muslim. We couldn’t have done anything.” I’ve read about the group appropriating the word for “lemons” as their badge of honor—the same epithet used for years by the HRM to denounce Muslims who supposedly curdle the country’s milk-and-cream Hindu population.

The street lapses back into silence. The sun just manages to clear the empty buildings that run down its trash-strewn length. From the direction of the rays, it seems the Limbus are headed west. Is that the direction in which Karun awaits? Sarita is unresponsive when I ask her destination. “Bandra,” she finally reveals. “My husband is there, at a guesthouse.”

I’m tempted to press her for the exact address, but I know she’s still mistrustful of my helpfulness. “I actually need to make it further north to Jogeshwari to see my mother, so Bandra is on the way,” I say to assuage any suspicions. “Is your husband east of the railway line or west?”

“West. Near the water.” I try to get more details by engaging her in conversation but she rebuffs me with monosyllabic replies. Perhaps she’s still shell-shocked.

I wonder how to proceed. In addition to the Limbu-infested areas in between, we’re also cut off from Bandra by the expanse of Mahim creek. Rising sea levels and repeated monsoon floods have extended this breach all along the Mithi river, which at one point was little more than a canal emptying sludge into the creek, but now has widened into a chasm. The most direct way across the water is to go back and follow the train tracks, but the Limbus probably have that staked out. The alternative is to aim for the Mahim causeway bridge ahead—perhaps there will be a crowd of people crossing, and we’ll stick out less. Except I can’t quite imagine blending in with Sarita all decked up like a lollipop. “They wanted me to be one of Devi’s maidens,” she explains apologetically when I ask about her outfit. “It’s even supposed to glow when it gets dark, just like Superdevi.”

“Well, we’re in Mahim now. If you don’t look Muslim, we’re both dead.”

“But there’s nobody around.”

“Not here, not in this no-man’s-zone—the Limbus probably cleared it out as a safety buffer. But ahead, there’ll be people everywhere. When the rioting started, Mahim is where thousands of Muslims fled.” I hand her my handkerchief. “We’ll figure out the sari later, but let’s start by wiping off your forehead.”

Sarita smears off her bindi and bridal dots and returns my handkerchief—the stain on the cloth looks a dark and clotted red. She runs her fingers nervously through her hair. “Won’t they still suspect?”

“Not if we say you’re my wife. Mrs. Hassan. That’s my name. Ijaz Hassan, not Gaurav. You must have guessed back at the hospital that I’m Muslim.”

Sarita looks startled, and I realize I may have committed a terrible blunder. What if Karun has mentioned me to her and she’s recognized my name? To my relief, it’s the thought of playing the begum to my nawab that flusters her. I remember how she fled when I first tried to talk to her in the hospital basement—who knew the Jazter came across as such a predator of female flesh? “Couldn’t I be your sister instead?” she asks.

That would certainly ease her worry. Except, even with her features half obscured by shadows, one can tell there’s no resemblance. About to be paralyzed once again by the conundrum of what Karun could have seen in her, I remember her looks won’t actually matter. The rules in this new Mahim decree that women remain properly veiled, so it’s fine to play my sister.

She’s not pleased when I explain this to her. “You mean I have to keep my face covered?”

“Actually, your whole body. We’ll look for some cloth to use as a burkha—to conceal your sari as well. The Limbus call the shots—I hear they go around punishing infractions with whips.”

We decide that she’ll be Rehana Hassan, my virginal and impeccably virtuous younger sister. Maybe not too virginal, since the story is I’m escorting her to rescue her ailing husband, who’s stranded in Bandra. “Where will we spend the night?” Rehana inquires.

“At the best boutique hotel in Mahim. We’ll pay my dear cousin Rahim a visit.”

ONCE MY PARENTS’ return shut down our research lab, I tried to find other venues to facilitate Karun’s experimentation. He quickly dismissed my usual haunts: the beach at Chowpatty was too exposed, the alley near the Taj too seedy (I didn’t even bother suggesting the Bandra station facilities). I tried reasoning with him, pointing out that the city didn’t offer anything more hospitable. Hadn’t he come to Bombay after reading about park activities on the internet? What, exactly, did he now expect? Surely his training had taught him to take risks, to show some spunk, if not for his own fulfillment, then at least for the cause of scientific research?

But he remained unmoved. The tale of the Jazter and the physicist might have ended there, had not the Mumbai University library come to the rescue. Although I had often looked up to see the gothic structure indulgently witnessing my plunge fests at the Oval, I had never before stepped into its august halls. The place was cool and silent when we entered that afternoon, stained glass windows soared towards the cathedral-like ceiling. The books looked appropriately old and solemn, dusty tomes with cracked binding locked away in glass-paned wooden prisons. We stumbled upon the door behind a cupboard in a deserted reading room. It blended in so perfectly with the dark wood of the walls that only the presence of two small bolts, also painted brown, gave any indication it wasn’t just another panel. Opening it and stepping over the knee-high base led to a tiny balcony which time (and the staff) seemed to have forgotten. The floor was filthy with bird droppings—in fact, several pigeons burst into energetic flight as we emerged (though a few continued cooing in the eaves, unconcerned). Two stories below us stretched the verdant greens of the Oval, to our right rose the university clock tower, Mumbai’s own Big Ben. “The heart of the city, and no one knows we’re up here. This is perfect,” I said.

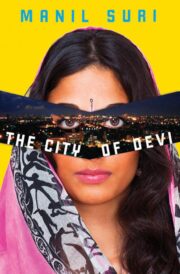

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.