Mr. and Mrs. Iyer came up to check on us after that evening’s bombing attack. They mentioned in passing that the conference was cancelled three weeks ago—had Karun been planning his escape since then? I dialed the number he’d given me, but it kept returning a busy signal. The next morning, when the new communiqué about Pakistan’s threatened nuclear attack appeared, I called again. I kept trying day after day without getting through, until the electricity failed and the phones went dead.

THE TRAIN PICKS UP SPEED. I keep my eyes averted out the window. Mura comes over and gazes with me at the houses going past. Only their tops are visible now, the rest obscured by a wall in between. “I remember when I was a child, we used to ride the train every Sunday to visit my uncle in Goregaon. There weren’t so many houses then, or walls for that matter—at Santa Cruz, one could see all the way to the planes parked at the airport.” He begins to caress the back of my neck. “Did you grow up in the suburbs or the city?”

I brush his hand off my body, but he manages to latch onto my fingers. He buries his face into my hair and inhales deeply. “Ah, that lovely fragrance convent school girls have. Is it the shampoo or the soap or just that wealthy South Mumbai scent?”

I turn around to try and squeeze away but he has me cornered against the wall. “Very educated, are you? College, probably. That’s why you’re not very impressed with our devi. Look at Guddi and Anupam, all bubbling with excitement. So completely convinced Devi ma’s come to save her own city.”

“You mean she hasn’t? How devastating to hear that. This whole train and bridal charade you’re putting us through, and you don’t even have a devi?”

“Oh, we have her all right. Even better than in the movies, you’ll see. The crowds worship her, even if convent girls like you don’t believe.”

“And you do believe? That she’ll protect us from the Pakistanis? That she’ll open her heavenly parasol to block their bombs on the nineteenth?”

Mura draws back. “Nothing’s going to happen on the nineteenth—it’s just a rumor the Pakistanis have been spreading to scare us. Who makes such an announcement if they really mean to attack?—they’d have simply launched by now, most assuredly. Or rather we’d have, even earlier, to beat them—if the threat seemed at all real to our military. Surely you could figure this out with your college degree?” He peers through his glasses to appraise me. “That’s the whole beauty of Devi ma, don’t you see? She gets to save Guddi and Anupam and the crowds flocking to her, keeps her promise to rescue Mumbai, without having to do anything.”

“And what if you’re wrong? What if the warnings are correct?”

“They’re not, but we’re prepared for any eventuality.”

“Who? You and your devi?”

“Not the devi, Bhim. Do you really think he wouldn’t have taken precautions—someone so visionary? I can’t go into details, but if the Pakistanis do try any mischief, he’ll make sure we’re the most protected souls in the country. Which includes all of Devi ma’s maidens, incidentally. So you’re lucky I picked you—perhaps you could show some gratitude to me.”

Mura comes closer again, and runs a hand through my hair. “So what do you say? In return for saving your life—surely you can agree to such a little thing?” He leans forward to kiss me.

I lay my palms on his chest as if in acquiescence, then push him hard. He topples over easily, tumbling across the floor like a plump and comical baby. He gropes for his glasses and locates them underneath his own body. One of the arms has snapped off. “How will I see with them now?” he asks mournfully, staring at the piece in his hand.

I am at the door, banging for the girls, when he is upon me. He rams his head into my back, knocking my breath out. I turn around, and he batters me again, like a fat and hornless goat, this time between my breasts. The impact of the blow sends me falling to the floor. The pomegranate rolls out of my sari, and the first thought that flashes through my mind is that if he tastes it, he’ll be further crazed by its aphrodisiac properties.

But he pays it no attention. Instead, he squats over me as I lie there trying to suck air back into my lungs. “Such a small favor I ask.” His face is red, he wipes tears from his eyes. “And instead, what do you do? You attack me.” I try to sit up, but he pushes me back. “Convent girls—do they all have to be so haughty?” He holds me down and stretches out atop me. His body is soft and unnaturally yielding—even his lips on my neck feel spongy. “Please,” he whispers, “it’s not too much.” I can still detect the peanuts on his breath.

I nod to buy time. “But not on the floor, not like this.” Surprised, he peers at me to see if I’m lying. I give him a reassuring smile. “As you put it, for saving my life.”

He helps me to my feet, and leads me to the berths. I stall by prodding the cushions on each, pretending to look for the softest. I’m running out of ploys and Mura out of patience when the undercarriage shudders—a sharp crack from below interrupts the steady rumble of wheels. Metal grinds noisily against metal, the compartment buckles and lifts, and to my disbelief, I see the wall outside the window closing in. I have just enough time to cover my face before we plow through, before a barrage of brick and mortar bursts in. The room tilts precariously around me, flinging me against a berth—then rights itself miraculously, the instant before tipping. A line of building façades whizzes by—I realize the train has left its tracks and is thundering down the center of a road.

Except that it’s not quite the center, but an angle at which we hurtle—an angle that brings us closer and closer to the buildings streaming past. We mount something, the edge of the sidewalk perhaps, and the jolt dislodges the pomegranate from its hiding place. It lifts off the floor and sails by my face, serene as a flying saucer, as I vainly try to snare it. I imagine myself airborne as well, the walls around me weightless, the train a rocket launching into space. As the moment of contact arrives, gravity gives us a pass, and we rise above the buildings instead of crashing into them. The scrunching of metal, the splintering of wood—all the sickening sounds of impact surrounding me fade. We arc through the air, the compartments liberated from their earthly existence, our persons conveyed heavenward by the freed spirit of the train. I look down through the clouds at the long trail of Mumbai that stretches below us—from the string of suburbs unwinding north, to Colaba at the southernmost tip. For a moment, as we peak, everything is still. Then we begin our descent back to the city where Karun awaits.

JAZ

6

AS I WATCH THE WAR-POCKED LANDSCAPE GO PAST, I WONDER again what my life would have been like had I never met Karun. Calmer, probably. Longer, too. To think that a single chance encounter has led to this wood and metal coffin in which I brace for my doom. Sweet, innocent Karun, as alluring as a blossom of the deadly datura and about as harmless. Samson had his Delilah, Adam his Eve, and the Jazter had you.

Already, I can see my epitaph. “Here lies Jaz, lover of his fellow men, done in royally by one of them.” With a warning for others of my ilk (hunters—shikaris—I like to call them) inscribed on my tombstone. A list of cautionary signs to watch out for—the most flagrant being that even now, risking life and limb and that one other most imperiled appendage, all I do is search this benighted city for Karun.

I look at the scratches on my arms, smell the sulfur in my hair. Has the Jazter really been reduced to this? The mud on my designer high-tops, the stains on my Diesel denims—what possessed me to subject my kickiest threads to such risk? Then I remember—Karun, whom I must find, whom I need to dazzle, whose rectitude I hope to penetrate.

Perhaps I’m too easy with the blame. With the impending bomb, the Jazter goose, not to mention his jeans and sneakers, are scheduled to be cooked anyway. I’ve rarely planned ahead, so no sense lamenting lost opportunities for escape. It might have been nice watching all this action from afar—say on the giant screen in Times Square. Except most of New York, for all I know, has been burnt to a crisp.

Since the future’s so iffy, I’ll turn my attention to the past. The underfoot clickety-clack marking out my remaining minutes begs to be drowned out with nostalgia anyway. I tune in to the sounds from twelve years ago. Children laugh and shout on the swings. Mango trees around me rustle in the wind. I sit in the park near Cooperage, waiting for the hunt to begin.

IT WAS DUSK when I first saw Karun. He looked much younger than all the parents milling around with their kids, which made him instantly suspect. He sat on a bench between the slides and the swings, an unopened book in his lap. He was trying very hard to be inconspicuous, I could tell.

I’d walked over after college to the park, to check out the evening’s prospects. A teenager showing off his shiny new Reeboks. A bearded young Bohri promenading his burkha-clad bride. Day laborers out for a smoke, their arms dusted white with gypsum. I leered at them all with scrupulous impartiality. The couples, as usual, were clueless. The shikaris would know I was one of them.

My gaze kept returning to Karun. Such a fawn, he might even be younger than myself. His chin as smooth as his cheeks, his hair cut so short that his ears stuck out, his lips announcing a hint of succulence. Did he have enough meat on his bones, though, to warrant a shikari’s interest?

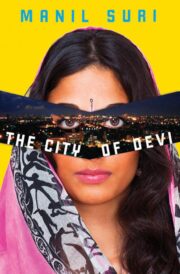

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.