The train engine toots, and I see we have already passed the Bombay Central bridge. I can always slip away at Santa Cruz and make my way south, I think. Yes, I will audition for Mura, I say.

Guddi and Anupam squeal in delight. Even Madhu seems to thaw a little—as the other two open jars of makeup and ooh over them, she starts curling my hair with a brush. “Guddi, find that memsahib wrinkle cream. Anupam, get some water from the thermos and wipe her arms clean.” Her brush snags on grit, which she pulls out with a harsh tug. “Isn’t it difficult enough as it is, that your hair had to be snarled like this? What did you do, rub in handfuls of dirt?”

The girls want to paint my fingernails with polish, but Madhu declares it will take too long to dry. “Just do the cheeks and lips, and let’s hope for the best.” She arranges a necklace that cascades in a series of filigreed chains down my neck and threads heavy gold earrings through my lobes. They all stand back to look at me—my face feels caked with makeup. “She’ll look younger after you finish painting on the bridal dots.”

Once I’m all decorated, Madhu insists I put on the “magic” sari. “It really does glow, believe me, but only if it’s pitch-dark. In any case, your salwaar is filthy—do you really think Devi ma would tolerate anyone in such a rag?” I realize my mistake as soon as I change—neither the sari nor the petticoat underneath has a pocket, and I’m forced to wrap the pomegranate in the folds at my waist and hope for the best. As I sweat under the layers of heavy silk, Guddi and Anupam express delight at how bride-like the bright red color makes me look. Even Madhu grudgingly says that I no longer resemble their aunt. She draws the hem of the sari over my head and leads me to Mura’s door, as if it is my wedding night. Just before turning the knob, she pauses. “I almost forgot to make sure. This month—have you already had your flow? We don’t want to get Devi ma unclean.”

THE TENOR OF THE CITY OF DEVI campaign changed abruptly. We awoke one morning to find that a phalanx of fifteen-foot Mumbadevi statues had invaded Mumbai. “It’s a showcase for all the tourists coming to our city,” the new campaign chairman, rumored to be an HRM man, explained. “So they can appreciate all the splendor and magnificence of Devi ma.” The statues, however, projected more belligerence than beauty—ominous warrior figures with coarsely fashioned features, set identically in concrete. Many of them popped up next to crowded Muslim localities unfrequented by tourists, where their towering presence could cause the maximum provocation.

Soon after, the HRM-allied municipality banned the sale of meat on Fridays in deference to the mother goddess. The very next week, it issued an order directing all public establishments, including places of worship, to immediately start displaying the City of Devi logo. When churches and mosques protested that they found its image of Mumbadevi offensive, the HRM chairman, Shrikant Doshi, responded personally. “Devi ma only reveals herself to those who believe. Anyone who claims to see her in the logo can’t then claim to be a true Christian or Muslim.” His thugs issued ultimatums around the city, beating up non-compliant mullahs and priests, vandalizing their mosques and churches. In retaliation, mobs set upon Hindu temples, stabbing two priests at Babulnath and destroying some of the outer shrines at Mahalaxmi.

The riots that ensued permanently changed the character of the city. Even after they abated, an atmosphere of heightened animus, of extreme mistrust, lingered between communities.

I REMAINED ONLY passingly attentive to the City of Devi tensions, so immersed was I in my “Project Karun” diary. The milestone of our hundredth star was fast approaching. The day I logged it, I couldn’t resist some calculations. Our performance had a weekly mean of 4.35 stars over the past five months or so, with a standard deviation of 2.72. If I ignored everything before Jaipur, the mean jumped to 6.67 stars per week, with σ = 1.44. I had no idea if these statistics were good, if they agreed with what might be normally expected.

“The average seems a bit low for newlyweds,” Uma opined. “But why worry? You now know his machinery works, and that he’s probably not a homo.”

“Thanks for being so sensitive.”

“Sorry. All I mean to say is that if you’re having fun, then the numbers are right—it’s the only thing that counts.”

We were having fun. Karun still waited for me to initiate things, but I found, to my surprise, that I enjoyed taking the lead. Sarita the huntress, Sarita the tigress out to get her meat—surely there existed a goddess embodying these pursuits whom I was channeling?

More importantly, Karun had become an essential part of my life. I loved being woken up in the morning when he clambered back into bed to share his mug of cinnamon coffee. We read the newspaper over breakfast, trying to catch flaws in “scientific” polls and studies, marveling at the latest lapses in politicians’ logic. I never knew what culinary experiment awaited me on evenings I worked late—once he even surprised me with Vietnamese. His Indo-Italian fusion had actually begun to taste rather wonderful, ever since Professor Ashton had mailed him packets of herb seeds from Princeton (we now had such European plants as sage and rosemary growing on our balcony). Sometimes, I discovered basil sprigs tucked into the folds of my towel—one day, I opened my cupboard to find sachets of lavender nestling between the saris. Each night, I liked to casually brush my toe against the hairless patch on his ankle for reassurance before closing my eyes. Our sunflower sheets grew softer, acquiring a silky smoothness over time.

The day my father suffered his heart attack, Karun held my hand all the way in the taxi to the hospital, his face as flushed, his knuckles as white as mine. “I’ve been through this when I was eleven,” he whispered. “I know what it feels like.” On the nights I kept watch, he insisted on staying behind with me—we sat till Uma relieved us at dawn, in adjoining chairs by my father’s bedside. At home, he nursed me as if I were the patient, fortifying me with minestrone and vitamins, assuring me everything would be fine. Perhaps these ministrations did have some trans-curative effect, because my father was back to walking around at home in a fortnight.

I realized how much I’d come to depend upon Karun, to love him, to know him since we married. He was too reserved to reveal himself to everyone—one had to be chosen for this opportunity. Even then, I felt like a bee burrowing into a tightly closed flower bud, each whorl of petals yielding to reveal another nestling inside. Despite how deep I advanced, I could still sense some mystery enfolded at his core. A secret, a treasure, an inadvertent lure, waiting for me to discover in time.

Perhaps true consummation, the traditional way, was part of this promise, this enticement. The huntress would have to persevere longer to earn her four-star trophy. I was willing to wait, to proceed only when Karun signaled his readiness. Until then, our limited repertoire of “Jantar Mantar” (as we’d begun to call it) would be enough to sustain me.

Uma’s pregnancy forced me to rethink my strategy. How would we ever form a trinity if Karun never got any closer to impregnating me? I reminded myself it wasn’t a pressing issue—although we’d discussed the family question before our wedding, it hadn’t arisen since (somewhat surprisingly). Once Uma delivered, though, the sight of my tiny new nephew at her bosom filled my own breast with longing. I had just crossed thirty-three—how close was the expiry date on my biological battery?

So I broached the topic unambiguously one night. “It’s been a year and a half—perhaps we should try it differently? The usual way other couples do so—what do you think?”

Karun colored immediately. “So that we can be a family of three,” I added to take away any sting.

Despite his unease, Karun agreed to my proposal of working towards it over the next few weeks. Each night, with his eyes closed, he embarked on this new exploratory mission. I tried not to make any movement that would startle him, even stifling the impulse to look down, much less stroke him or guide him. Instead, I mentally transmitted welcoming vibes his way—my encouragement, my appreciation, my empathy.

The barrier I needed to help Karun cross seemed mostly psychological. Sometimes he wilted too quickly, but on most nights he stopped even though physically still primed. Uma told me to try pomegranates. “It’s the desi alternative to the oysters they prescribe in the West. The Kama Sutra says to boil the seeds in oil, but in my experience, a glass of juice right before works just as well.” Karun seemed puzzled by all the freshly squeezed nightcaps I began serving, so I extolled their antioxidant benefits, telling him a bedtime dosage worked best. Hazy on the Kama Sutra instructions, I erred on the safe side by also downing a shot myself.

I shopped for pomegranates at the market near work—red ones rather than gold, because they clearly displayed the ardor I felt befit an aphrodisiac. I learnt to distinguish between the different varieties—the “Mridula” with its voluptuous crimson interior, the “Bhagwa” with its smooth and glossy skin (fruits from Satara were always the juiciest). I became an expert at separating the arils from the bitter white pith, at squeezing out every last drop of succulence. In a pinch, I brought home the bottled variety of juice one evening—it tasted flat and spiritless, nothing like the fresh.

We both got addicted to our bedtime tonic. Perhaps Karun guessed its purpose, even though I didn’t confess. Each night, we tasted pomegranate on our first kiss—a few times, I noticed my nipple was tinged red. I wondered if the scent mixed with my own after Jantar Mantar, if I left telltale traces on Karun as well. Sometimes I saved a few kernels to sprinkle on our cornflakes the next morning, to carry over the spell.

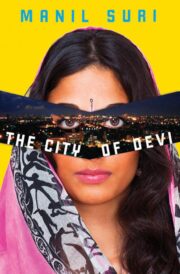

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.