It’s been several years since my visits here with my mother and Uma. The stone steps were smooth and polished then, the aquatic creatures carved on the walls didn’t have heads or fins missing. Most wondrously, a family of seahorses glided in a window by the entrance like some mythical aquatic tribe. Their display tank is empty today, the entry doors chained and padlocked.

About to turn away, I remember the fish and chips café in the compound, where we gorged on crisp pomfret after each visit. Is that why fate has spurred me here today, to satisfy my seafood craving? Uma always commented on how macabre the location seemed, as if the whole point of the aquarium exhibits was to stimulate viewers’ appetites. I tug at the handle and rattle at the chains, but the café remains securely locked. The door leading to the second-floor canteen, though, opens when I try it, and I scurry in.

Upstairs, the floor is covered with dust and broken glass. I walk into the kitchen and the pungency of fish assaults me almost at once. Am I imagining it?—has the machiwalli hallucination from the hospital returned? Or could years of frying have insinuated the odor into the walls? I begin to notice other things—the kerosene stove, the bottle of oil, and in the dark corner by the cupboard, the figure of a man lying curled up on a mat.

He awakens almost as soon as I spot him, and lifts himself groggily up on his hands. “How did you get in here? What do you want?”

He is barely twenty, but there is already a gauntness to him going beyond the war weariness I have seen in people’s faces. He looks as if he has been fighting an enormous personal battle, with little success. “Are you the cook?” I ask.

“The cook?” He scrambles up to a sitting position, umbrage clearing the sleepiness from his face. “Do I look like the cook to you?”

For an instant, I wonder if I’ve stumbled upon a Khaki, given his rumpled khaki shirt with the epaulets flopping unbuttoned at his shoulders. Then I notice the aquarium logo stitched over his pocket and realize he’s the watchman. He seems mollified by this. “I have a rifle downstairs, you know,” he adds, as if to impress on me the powerfulness of his position. He takes out a large ring of keys from his back pocket to display as further proof, whisking them away as if afraid I will try to touch them. “Why are you here?” he demands.

“I came looking for fish.”

A wary look springs to his eyes. “The display tanks are in the other building—”

“I meant to eat. Isn’t this the canteen?”

“The canteen? Does it look open to you? Can’t you hear the bombs falling outside? Where is the fish going to come from, fly into your lap from Chowpatty?” He shakes his head. “There’s no fish. Now go away.” He turns around and spreads himself out again on his mat.

I’m about to turn away when I spot a waste basket next to the cupboard. Sticking out from under its lid is a fish head, its eye dried open into a stare. “See?” I cry out, waving the lid in the air. “See, I could smell it. Someone has been eating fish.”

The watchman springs back up. “Are you accusing me? Are you saying I ate that fish?”

I’m startled at his vehemence. “I’m not accusing you of anything.”

“Anyone could have sneaked into the aquarium and pulled out a fish. How do I know who did it? Do I have ten heads that I can keep track of everything? And what am I supposed to eat—do you even know how long it has been since I’ve been paid?”

I wonder if he is asking for money. Perhaps I should offer him some of the notes tied in my dupatta. “Look, Bhaiyya. I haven’t eaten either. If you can bring me a fish, even a small one, I’ll give you two hundred rupees.”

Instead of calming him, my words make him flare up. “How dare you insult me with such a bribe? You think I’m going to hand over the very creatures I’m supposed to protect? You think I have no self-respect? Why did you come here, memsahib, just to spit in my face?” He wraps his arms around his sides and hugs his body, rocking back and forth slowly on his heels, as if to comfort himself after my calumnies.

“I’m sorry,” I say, backing away towards the kitchen door. “I didn’t mean any harm.”

I am almost at the door, ready to turn around and escape, when he looks up. “Four hundred,” he says.

AN UNDERGROUND PASSAGEWAY connecting the two buildings leads us into the aquarium. Hrithik (not his real name, he confesses, but one he has decided to adopt after his favorite film star) tells me there might still be a few of my cherished seahorses around somewhere. “Though they’re not very tasty.”

The exhibits inside have no illumination, so Hrithik lights a candle. “These days, there’s only enough generator oil to run the filters,” he explains. “Not that there are too many tanks with anything left.” He shows me a panel behind which tiny candy drop fish make small kissing gestures as if thanking him for the light. “I never tried these, I was always told the colorful ones are poisonous.”

As we pass case after empty case, I realize just how many fish are missing. Could Hrithik have eaten them all? Perhaps he reads my mind, because he starts talking about how easy it is for fish to fall sick, the lack of food and supplies, the pressure to sell the best specimens to foreign aquariums. “For a while, we were getting live carp and pomfret for the restaurant and storing them temporarily in these tanks, just so that the visitors had something to look at.”

We come to the central tank, illuminated by sunshine through a skylight above. A large ray floats by, exposing the various organs on its underside for me in a languorous display. Hrithik shakes his head subtly to indicate its lack of culinary quality. “Look, there,” he says, pointing at a shadowy shape circling further back. “Very good to eat. Only one left.”

“But it’s a shark.” I can tell by its triangular fin. A small shark, a baby perhaps, but a shark, nevertheless.

“It’s the tastiest one left. I’ve been trying to catch it for weeks, but he always escapes. Look.” He shows me a scar on his neck, and another one across his arm. “All over my body, especially on my chest. Once he even tried to bite off my leg.” He stares at the water with animus on his face. “It’s not possible to trap him—not by myself alone. But if there was another person—” He looks at me slyly.

“Something smaller would be better.”

We settle on a fish with a blunt head and speckled skin that is swimming alone in one of the tanks further on. The fish seems quite dazed and lethargic, and doesn’t flop around too much in the net when Hrithik scoops it out. “It would be dead in a day or two anyway,” he reassures me.

In the kitchen, Hrithik uses only a few stingy drops of oil in the pan, with the result that the fish comes out more burnt than fried. The flesh is mushy and unpleasant, and there are no spices to camouflage the bitter aftertaste. It’s nothing like the machi-fry I craved, but I eat as many of the pieces as I can stand. Hrithik wolfs down his share and whatever I leave of mine, acknowledging that the flavor is not good, and reminding me he recommended the shark.

The all-clear signal sounds as we finish. Pulling out the money for Hrithik, I notice the satiation on his face giving way to an inexperienced leer. “You don’t have to pay me the full amount,” he says. “Just stay awhile. It’s not so safe outside, and I have an extra sheet here.” He smirks.

I throw the notes at him. “I’ll take my chances. Maybe you should ask your mother for permission first before you make such an invitation again.”

His bravado crumbles immediately, and he doesn’t meet my eye. I am at the door when he calls out. “Come back tomorrow and help me with the shark. You can eat as much as you want for free.”

4

APSARAS FLITTED IN TO AWAKEN US WITH THE STRUMS OF THEIR celestial instruments the morning after our wedding. We had barely noticed the images from the Ajanta caves decking the walls of our bridal suite the night before: Bodhisattvas contemplating lotuses, maidens comforting their swooning princesses, even the Buddha gazing down (perhaps a bit too ascetically) on the newly betrothed every evening. In light of how things had played out between Karun and me, I felt relieved we hadn’t booked the Khajuraho suite.

We breakfasted on the balcony. The décor took generous liberties with historical consistency: ornate Mughal chairs stationed around an Ashok chakra table from Mauryan times; railings, arches, and decorative flourishes that gleefully seesawed between north and south, old and new, Rajput and Dravidian. It hardly mattered—not with the sands sparkling up and down the coast, the waves rolling in with hushed booms, the sun falling on Karun as he selected fresh apricots from a platter and peeled them for me. Afterwards, we walked through the lobby, redolent with the fragrance of thousands of tuberoses this morning, to explore the exotic flowering plants in the outer courtyard, imported all the way from Hawaii.

We’d both brought our swimsuits, since this was our chance to finally experience the exclusive waters of the hotel swimming pool. The guard simply bowed us through without even checking the guest cards that now proved our legitimacy. The carved pillars and cascading steps cut into the long edge gave the pool a ceremonial air, like something one might come upon in an inner temple courtyard. How magical the water felt, how pure and vitalizing, like a baptism ushering us into married life. I wanted to reprise our first kiss, but felt too self-conscious and settled instead for a quick peck beneath the surface. We gave up on the idea of exploring the rest of the hotel, splashing and swimming almost until checkout.

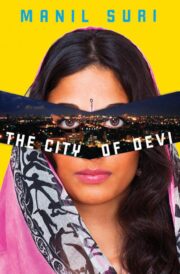

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.