‘How pretty you will look in some lovely clothes!’ cried Aunt Louise.

‘I am always dressed like a little girl.’

‘That will not always be so. I will send you some clothes from France.’

‘Oh, Aunt Louise, how lovely. I wonder if Mamma will let me wear them! But of course she will, because Uncle Leopold will approve. I should so love to look like you, Aunt Louise. But I never shall because I am not so pretty.’

‘Nonsense, nonsense,’ said Louise. ‘We are as sisters … Ah, that is pleasant. We shall be sisters. Could you think of me as such?’

‘Oh, Aunt Louise, I could, I could.’

She was sober suddenly.

‘What is wrong?’ asked Louise.

‘I was just thinking how sad and dull everything is going to be when you and Uncle Leopold have gone.’

And the end of their visit was coming near. Victoria tried not to think of it, but it was impossible not to.

‘I almost wish,’ she told Lehzen, ‘that it had not all been so perfect, then I should not be so sad.’

‘Come, come,’ said Lehzen. ‘You will see them again. They will visit you.’

‘They did not for more than four years.’

‘But your Uncle writes you lovely letters and your Aunt will now that you have met.’

‘I feel so sad,’ sighed Victoria. ‘I could weep.’

‘You must be gay for their last days.’

But Victoria found this difficult. She had a headache and she felt sick.

She braced herself to be gay for the next few days; and when Leopold and Louise took their leave and she, with her party, saw the steamer with the Belgian flag sailing away, she could make no more attempts, and Lehzen taking her hand cried out in horror.

‘How hot you are! I think you are letting this departure upset you too much.’

‘They have gone,’ sobbed Victoria. ‘It is all so dull without them.’

‘I should go to your room and lie down,’ said Lehzen. ‘I will sit with you.’

Victoria felt too listless to disagree. She allowed Lehzen to lead her to bed and when she was there she sank into a sleep immediately.

In the morning she felt faint and sick and in great consternation the Duchess called in her doctor.

Within the next few days it was known that the Princess had an attack of typhoid fever.

Chapter XVI

AN INTRUDER IN THE BEDROOM

Lehzen was in constant attention, snatching only a few hours sleep each night. The Duchess was unsparing of herself; Victoria was ill; all her hopes rested on this girl; Victoria must get well. She could not be submitted to ordinary nursing; Lehzen alone was to be trusted with the precious creature and between them the Duchess and the Baroness nursed Victoria.

All through those dark October days in Ramsgate Victoria lay in her bed – not aware of where she was or what was happening about her. Lehzen cut off her hair and wept to see the thin little face – so unlike her blooming charge’s. The flushed face, over-bright eyes and incoherent babbling terrified her.

The climax of the illness came at length and with great relief the Duchess knew that it was only a matter of building up her daughter’s strength and convalescence.

‘She is scarcely recognizable,’ said the Duchess to Sir John. ‘This has been a sad fright for me.’

‘She’ll recover. Our Princess has a very firm grip on life.’

‘Indeed she has. Poor Lehzen! She has not slept for nights but she’s almost gay – if you could ever imagine Lehzen gay – now that she knows the worst is over. She hardly likes me to be in the sickroom. As if I would disturb her darling. I suppose I should be furious with the creature but I know it is only out of her devotion to Victoria that she behaves like a tigress with her cub.’

‘And whose cub is she?’ asked Sir John with a smile. ‘Lehzen has too high a conceit of herself. I’ve always thought we could do without her.’

The Duchess sighed. It was one matter over which she had had to stand out against Sir John. It was an indication too that Victoria already had some power; because both the Duchess and Sir John knew that to attempt to remove Lehzen would set Victoria completely against them; and there was no doubt that she would enlist the help of the King and Queen which would be readily given. In fact the King would like to take Victoria from Kensington and have her brought up in his household. A fine prospect, to have her running wild with the ‘bastidry’ and indulged and pampered by the foolish Adelaide.

‘Well,’ went on Sir John, ‘she is on the way to recovery now. And when I think that in less than two years she will be of age I am very apprehensive.’

‘Perhaps we concern ourselves too much.’

‘Most young people turn against those who have directed them in their youth – once they have escaped from that vigilance which has maintained them. I feel sure the Princess will be no exception.’

‘I shall see that she is!’

‘She will be surrounded by those who seek places. I do think we should make sure that we are at hand to guide her. You as her mother will certainly be, but I think I should have some post which will ensure that I am at her side.’

‘What post do you want?’

‘I think if I were her private secretary I could look after her, and you, my dearest Duchess, could be sure of seeing all important documents that came into our hands.’

‘Then you must be her private secretary.’

‘She of course will be the one to decide on whom to bestow the post.’

‘Then I say she shall bestow it on you.’

‘She will know that it is in her power to refuse; and she may go to the King.’

The Duchess looked angry. ‘Disobedience …’

‘Remember, my dear Grace, that she will be of age and the Queen. She will no longer be your dependent little girl. We have to go carefully.’

‘I do hope she is not going to prove ungrateful.’

‘I will speak to her, while she is feeble, and try to persuade her. There is a change in her. She will be less arrogant, more amenable on her sickbed.’

The Duchess nodded.

‘So I have your Grace’s consent to make this request to her?’

‘But of course. And it is, like all your plans an excellent one.’

There were long shadows in the room. She was supposed to be sleeping. Beside her bed Lehzen sat dozing. Poor Lehzen who refused to go to bed and must be on call day and night for her Princess. Victoria had seen her often sitting by the bed when her eyes refused to stay open; and Victoria smiled when she actually slept.

She thought: This is the nearest I have ever been to being alone.

She watched poor Lehzen now – the piece of needlework fallen from her hands, her head lolling forward. Dear Lehzen, let her rest.

I have been very ill, thought Victoria. Indeed, she felt very weak and quite hazy. Only this morning when she had awakened she had not been sure where she was. How glad she would be to be back in Kensington. It seemed years ago that Uncle Leopold and Aunt Louise were here. When she had looked at herself in the mirror which she had insisted on Lehzen’s bringing to her, she scarcely recognised herself – she was so pale and her eyes looked so big and protuberant; and her hair … which used to be so thick was now thin and lifeless.

Lehzen had assured her that it would soon grow thick again.

She felt so tired – too tired to think of how old she was getting and that she would soon meet some more cousins from Germany whom Uncle Leopold was so anxious for her to like.

She half dozed and then awoke with a start, for the door of the room had quietly opened and someone was standing there.

She wanted to scream for in her weakened state it seemed to her that evil had entered the room. He stood smiling at her – bold and wicked, for she was sure he was wicked – with that half sneering smile on his face. Sir John Conroy, the man whom she had hated, had come into her bedroom and she was unprotected, for Lehzen, worn out with exhaustion, was fast asleep in her chair and she herself, weakened by her serious illness, was unable to do anything but stare at him in fascinated horror.

He put his fingers to his lips and, glancing at the sleeping Lehzen in a way which angered Victoria, he came closer to the bed and sat down on it on the opposite side from that at which Lehzen sat.

‘What … do you want?’ stammered Victoria.

‘To speak to you,’ he whispered.

‘Not here … in my bedroom.’

He laughed softly – that beastly laugh which she hated.

‘It’s as good a place as any and you happen to be here.’

‘I am not strong enough to receive visitors. Lehzen will tell you …’

He laughed again in contempt of Lehzen. ‘I’m not an ordinary visitor, am I?’

That was true. He was certainly not like the Queen or the Duchess of Cambridge or poor old Aunts Sophia, Augusta or Mary. She did not feel well enough to see them, but at least they would come with the kind purpose of cheering her up. This man was sinister.

‘I am tired,’ said Victoria.

He laid a hand on hers which made her shiver.

‘Then we will settle our little business quickly.’

‘Yes, please,’ she said pointedly.

‘My dear Princess, I want you to make me a solemn promise.’

‘I should want to know first what you are asking me to promise.’

‘You are going to need a great deal of help in a few years’ time. You will need someone you can trust to be at hand. A position which will be of the greatest importance will be that of your private secretary. I want you to give me your solemn promise now that when you are Queen that post shall be mine.’

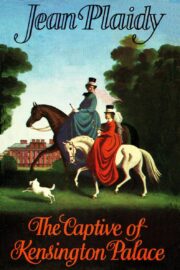

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.