Soon after her return London was shocked by the fire which destroyed the Houses of Parliament. The King grew overexcited and many people said it was an omen. The verdict was that had the fire been dealt with promptly the building might have been saved. But nothing had been done and a minor outbreak had resulted in a mighty conflagration.

There should be some means of preventing fires spreading, the Government decided; a kind of brigade which could go into action with the minimum of delay was needed.

William was excited and discussed it with Adelaide.

‘They seem to think there should be some sort of Fire Brigade – men just waiting for a call with everything ready to deal with the flames before they’ve done too much damage.’

Adelaide thought this was an excellent idea; and was very interested in the formation of the London Fire Brigade.

It was much more comforting to discuss the building up of such an organisation than the depressing affairs of the Government.

‘That fellow Melbourne has been to see me again,’ William told her. ‘He says he can’t get the support he needs and that he thinks the Government will have to make concessions to these radical ideas if it’s to stay in power.’

‘They cannot make concessions. It will be the Reform Bill all over again.’

‘That’s what I tell him, but he stands firm. Melbourne will have to go.’

‘Will this bring Wellington back?’ asked the Queen hopefully.

‘We’ll have to see.’

Shortly after this the King dismissed the Melbourne Ministry, an action which was ill-timed, for he had played straight into the hands of the Queen’s enemies.

It was well known that she had opposed the Reform Bill; she had no sooner returned from her trip abroad than Melbourne was dismissed. It was easy to see that the Queen wanted to bring back the Tories and that she was against reform.

The Times was the first with the news.‘The King has turned out the Ministry and there is every reason to believe that the Duke of Wellington has been sent for. The Queen has done it all.’

It seemed that all London was against the Queen. The FitzClarences discussed her in their Clubs and the houses of their friends with venom. The dismissal of Melbourne was an attempt to obstruct a Government influenced by the people. And this had been brought about by an ugly woman with a German accent who had come from a ‘doghole’ in Germany and had slept in a room which an English housemaid had scorned!

Adelaide was wretched. She almost wished that she had stayed abroad. William, oddly enough, was less excitable over major events than over small domestic difficulties.

‘Stuff!’ was his comment.

The people were parading the streets with banners on which were painted the words: ‘The Queen has done it all.’

‘You see,’ said Adelaide, ‘that is what happened in France. They chose the Queen because she was a foreigner to them, just as the people here have chosen me. I hope that I shall be as brave as Marie Antoinette when my time comes.’

The King’s ‘Stuff!’ was some consolation. ‘We all get mud thrown at us now and then. My brother George was the most unpopular man in the country but he died in his bed. Stop fretting.’

Wellington advised that the King should send for Sir Robert Peel and ask him to form a Government, and messengers were immediately sent to Rome where Peel was at that time. Meanwhile Wellington became First Lord of the Treasury and Home Secretary, and carried on the Ministry until Peel’s return. Then Wellington took on the post of Foreign Secretary.

Such a hastily formed Government was an uneasy one, although it sufficed to carry the country through a rather ugly situation; it did last for four months, and the campaign against the Queen subsided.

The Times even went so far as to publish an apology to her, and the Queen was relegated to the position of a rather stupid woman, a nonentity who had failed to give the King the heirs for which he had married her, who was not even handsome enough to grace ceremonies; and therefore was to be regarded with contempt.

The FitzClarences added their criticism. She was a fool; she had an execrable German accent; she was no use nor ornament to the throne.

Adelaide, painfully aware of her unpopularity, grew thinner and her cough returned to trouble her.

Buckingham Palace had now been completed and even that was used as a condemnation against the Queen.

There had never been such a lack of taste displayed in any of the royal palaces. Did the people remember George IV? He might have been extravagant and a voluptuary controlled by women, but at least he had good taste. Think of Carlton House; think of what he had done to Windsor; think of the buildings round Regent’s Park and Nash’s Regent Street. And then think of Buckingham Palace!

‘Every error of taste imaginable has been committed.’ The pillars – and there were many of them – were painted in a shade of raspberry. Thomas Creevy, the old gossip, had had a look over it and said those raspberry pillars made him feel sick and that instead of being called Buckingham Palace it should be called Brunswick Hotel.

The most vulgar thing of all was the wallpaper for the Queen’s apartments which she had chosen herself.

And this was the palace on which a million pounds had been spent!

William himself did not like it when he went to look over it with Adelaide.

‘I suppose we’ll have to move in. They’ll expect it of us … after all that money’s been spent on it.’

William was thinking of the FitzClarence grandchildren playing hide and seek behind the raspberry pillars. They would not like it he was sure. Not like Old St James’s for all its gloom, or Windsor for all its grandeur. And there was nothing like Bushy with its homeliness and memories of the old days with Dorothy when the children were all growing up and were much more respectful and affectionate towards the Duke of Clarence than they were to the King of England.

‘Why not offer it to the country?’ suggested Adelaide. ‘It could take the place of the Houses of Parliament.’

‘Capital!’ cried the King. ‘That’s what we’ll do.’

He was disappointed when the Government announced that it did not believe that Buckingham Palace would be suitable as the Houses of Parliament. Moreover, plans were hastily going ahead to rebuild them on that spot on the river where the old ones had stood.

How glad Adelaide was to go to Brighton for a respite! It was so pleasant not to have to worry every time she drove out that she would be confronted with one of those horrid placards about herself. The sea air was good too, even though it was autumn and the winds blowing in from the sea were bitterly cold.

One of her greatest comforts, apart from the grandchildren, was George Cambridge, who was growing into a very handsome boy, and was devoted to her. There was one who showed gratitude. But she had to face the fact that he was growing up and she supposed he would have to take up some training – military perhaps, which would entail his going away, probably to Germany where it seemed to be the custom to send royal Princes. But that was not yet and she would enjoy this period in Brighton.

The FitzClarences, however, would not allow her to be at peace, so they started a rumour that the Queen was pregnant.

When the Duchess of Kent heard this news she was wild with rage. She stormed up and down her drawing-room declaring that it was impossible. It could not be. That poor pale sick creature! How could it possibly come about? There was a mistake. Sir John must tell her it was a mistake.

Sir John did; but he shared her horror. If indeed it should be true, if Adelaide produced that child and it lived … then this would be the end of all their hopes.

Victoria said to Lehzen: ‘Do you think this story is true that the Queen is going to have a child?’

‘It has been neither denied nor confirmed,’ said the judicious Lehzen.

‘Lehzen, think what it will mean! I shall not be the Queen after all.’

‘My dear Princess, will that make you very unhappy?’

Victoria was thoughtful. ‘I think I shall be very disappointed. You see, everything that has happened has been leading up to that. But I can’t help thinking of Aunt Adelaide. She is a sweet kind woman, you know, Lehzen, and I love her dearly. I know what she wants more than anything in the world is a baby of her own. Oh, she loves all the King’s grandchildren – whom I am never allowed to see – and she loves the Georges and I believe she loves me too – when Mamma allows her to see me – but she does long for her own baby. So if I lost the throne and Aunt Adelaide gained a baby … Really, Lehzen, I can’t honestly say, but I think I should feel happy for Aunt Adelaide.’

Lehzen was moved to comment. ‘You have your storms and tantrums, but I think you have great honesty and that is a very fine characteristic to have.’

Victoria smiled. ‘I can’t help thinking too that George Cambridge has a much happier time than I do. He is not told he must not do this and that; he is allowed to be alone sometimes. So perhaps I feel too that there is a great deal to be said for not being the heir to the throne.’

Lehzen said calmly: ‘I am glad you see it in this way, because if you should not be Queen you will still make a very happy life for yourself.’

The Duchess was far less philosophical.

‘This is monstrous!’ she cried. ‘That old fool could not beget a child. And who is the man who is always beside the Queen, eh? Earl Howe. She is known to have a fancy for him. If the Queen is with child, then depend upon it, Earl Howe is the father.’

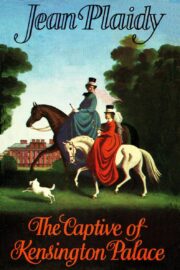

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.