Melbourne’s tragedy was that he married her; but no one could live in harmony with such a woman, not even the calm, intellectual Melbourne; and when Lady Caroline was involved in scandal with Lord Byron he could no longer live with her in any circumstances. They were separated; Caroline had died some six years before, and Melbourne, now a free man, devoted himself to art, literature and politics, and to his son, George Augustus, who was mentally defective.

Melbourne gave no indication that he had passed through such a tragedy. He was suave and handsome, and politically ambitious.

He accepted the King’s challenge and set about forming a government.

There was no great excitement about Grey’s departure. Melbourne was a good Whig and the Whigs had passed the Reform Bill. As long as Wellington – that arch enemy of Reform – was not brought back, the people were content.

Adelaide had a cough which persisted and William was worried about her.

She worked too hard, he said. That Reform business had upset her. She did not understand the English; she had believed that the country was on the edge of revolution and she was to be executed like poor Marie Antoinette.

She needs a holiday, said William to his daughter Lady Alice Kennedy, who had made Windsor Castle her home and brought her children there with her.

Lady Alice, who like all the FitzClarence family seemed to have grown very resentful of Adelaide since she had become Queen, said that a trip to her old home would be a good idea. There was that old mother of hers who could not live much longer; she was sure Adelaide would like to see her.

‘I’ll tell her she shall have a holiday,’ said William.

‘Will you go with her?’

‘A King has to govern his country, Alice. He can’t go dancing all over the Continent.’

‘I thought so, but she’ll protest and say she can’t go without you. You should arrange the trip for her and then tell her what you have done. She’ll be grateful to you for doing it that way and it will do her the good she needs.’

‘Capital idea,’ said William. ‘Leave this to me.’

He sent for Earl Howe who was still a member of the Queen’s household and, although at the time of the passing of the Reform Bill he had been forced to resign from the office of the Queen’s Chamberlain, he continued to serve unofficially in that capacity.

‘I want a trip arranged for the Queen,’ said William. ‘She’s not well. She wants a holiday. She shall go to her old home and see her mother. It’ll do her good.’

‘Has her Majesty agreed to this, Sir?’ asked Earl Howe incredulously.

‘No, no. It’s a secret. I shall just present her with the finished plans.’

Earl Howe was dubious as to the success of this, but he knew that the King was in too touchy a mood for him to suggest he might be wrong.

The King had been behaving even more oddly than usual lately and upsetting all sorts of people. Only the other day at a dinner where he insisted on making one of his interminable speeches he had talked of the changes in the Navy and how it was possible now to rise from the lowest rank to the highest. On his right, he pointed out, was a member of a family as old as his own, on his left, his good friend an Admiral who had risen from the dregs of society. The speech was received with astonishment and acute embarrassment by the Admiral on his left, but William was unaware of it. It seemed that there were times that if he could blunder he would do so. And he appeared to pass through periods when his mind was really unhinged.

No, decided Earl Howe, he dared not disagree with the King.

When Adelaide heard what plans had been made she was dismayed. As for the King his asthma had been worse than usual and he had felt most unwell. He hated the thought of losing her and would never have thought of a separation – however brief – if Alice had not persuaded him of the Queen’s need for a holiday.

‘I don’t want to go,’ Adelaide told him, when he explained the plan to her.

‘You must. You need a rest. That cough of yours … I don’t like it.’

‘I feel I should be here with you.’

‘I’ll miss you,’ said William. ‘I can’t think how I’ll get along without you. The Government … this fellow Melbourne … It’s all very shaky. I shouldn’t be at all surprised if the Government fell, and you know what, Adelaide, the people would blame you for it. They always blame you. They seem to have got it into their silly heads that I’m a dolt you lead by the nose.’

‘They’re fond of you,’ Adelaide told him. ‘They want a scapegoat so they’ve chosen me as the French chose Marie Antoinette.’

‘It’s not the same. You don’t know the English. Still, I’d rather you were away. There are those fellows from Tolpuddle … or some such place … those six Dorsetshire labourers taking oaths about trade unions … They’ve been transported and the people are making something of it. It’s nothing. Talk … just talk … All the same it upsets you, but I wouldn’t want you to be here. You’d like to see your mother, wouldn’t you? And your brother’s coming over to travel with you. I’ve arranged it all. There, you’ll like to see your home.’

‘My home is England now,’ she said. ‘My pleasure is in looking after you.’

He was deeply affected. ‘I don’t know what I shall do without you. There are a hundred ways in which you are useful to me.’

‘Then I shall stay.’

‘No, no, I can’t allow it. You must go. It’ll do you good. Go … and come back soon.’

So she left St James’s with her brother, the Duke of Saxe-Meiningen, and some members of the FitzClarence family; among the party was Earl Howe.

The Cumberlands had come home from Germany very sad because Baron Graefe had been unable to do anything for George.

Victoria wept when she heard the news.

‘Poor, poor George Cumberland. I must ask Mamma if I may call on him. He will be in need of comfort.’

The Duchess thought there could be no harm in Victoria’s visiting her cousin. No one would expect her to marry a blind man, she said to Conroy.

So Victoria called on her cousin and found him not in the least depressed. He knew that he would never see again. Victoria tried to imagine it. Never to see the flowers and trees, never to embroider, never to see Feodora and the dear children, Lehzen, Uncle Leopold’s letters, the beautiful singer Grisi. How tragic. How very, very sad.

‘Oh, Lehzen,’ she cried, when they were driving back to Kensington, ‘he looked so beautiful so serene, it made me want to weep.’

Chapter XIV

‘THE QUEEN HAS DONE IT ALL’

When Adelaide returned to England after her trip on the Continent it was to find the King ill and fretful. He was, however, delighted to see her, and when she arrived at St James’s Palace hurried out to welcome her and embrace her warmly.

‘I’m glad to see you back,’ he cried. ‘It’s not the same without you.’

It was a wonderful welcome home.

Many ceremonies had been arranged for her and by the end of a week she was exhausted; so that when the day came for her to go to the City to receive a congratulatory address on her safe return she was unable to attend and the King went alone. Adelaide’s detractors preferred to see this as an insult to the City although it passed off without much comment.

The FitzClarences had grown to dislike her actively, the main reason being that she had been so good to them, and their arrogant natures would not allow them to admit her generosity while they did not hesitate to accept it. Adelaide was the Queen; and they were the children of their father’s mistress. This was a fact they could not forget. They hated her for being in the position which they reckoned should have belonged to their mother; and they were constantly reminding each other of what life would have been if their parents had been married. The fact that the King acknowledged them as his children, that they had titles and honours, did not satisfy them. They wanted more, and to appease their frustrated anger, like the people, they chose meek Adelaide as their scapegoat.

At one moment she was a fool with no intelligence; at another she was possessed of great cunning. She led the King and she was responsible for his opposition to the Reform Bill; she was an alien – a German, and there had been too many Germans in the royal family.

Those who had accompanied her to Saxe-Meiningen reported that the Castle of Altenstein where she had spent her childhood was certainly not worthy to be known as such. They had seen the room which Adelaide and her sister had shared – a little room without a carpet and containing two small beds with calico curtains. An English maid would complain at being given such a room. And this was the woman who sought to manage the affairs of England!

While aware of this hostility Adelaide pretended not to see it because she did not wish to upset William. He loved his wife; he loved his children; in the early days of his marriage the harmony which had existed between them – and which was of Adelaide’s making – had delighted him; and his mind was not strong enough, Adelaide decided, for her to introduce new conflicts. She must forget the unkindness of William’s children and delight with him in the adorable grandchildren who made no secret of their love for her.

Windsor Castle and St James’s were the homes of many of them; they ran about shrieking and playing their games, and no one restrained them, for the King and Queen enjoyed hearing their noisy play; and if there was silence, began to fret that they might be ill.

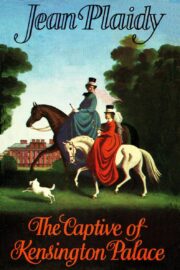

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.