‘She frowned when I criticised her. I do believe she thinks that she is of more consequence than I am.’

‘That may well be,’ said Sir John.

‘She will have to be checked.’

‘Lehzen spoils her.’

‘In her own stern way perhaps.’

‘Nevertheless it is spoiling.’

‘My dear, she would make such trouble if I sent Lehzen away. She would appeal to William and Adelaide.’

‘You have snapped your fingers at them quite often.’

‘Yes, but we must remember that until William is acknowledged to be mad he is still the King and he could be difficult. Nevertheless I am determined not to allow Victoria to imagine she can command us all … yet.’

A messenger had arrived with a letter for the Duchess. Sir John watched her while she opened it and read it.

When she had done so she threw it on to the table with a sarcastic laugh. Sir John picked it up and read it.

‘They suggest that you stop the salutes.’

‘Impertinence,’ said the Duchess.

‘Well, hardly that.’

‘I shall certainly not stop them. Victoria has every right to be saluted. She will be the Queen as soon as William is dead.’

‘My dear Duchess has overlooked one factor. William is not dead.’

‘I shall write back and tell them that I have no intention of depriving my daughter of her rights. As soon as this pier is opened I shall write to this … er … person and tell him so. Now I believe it is time we left.’

Victoria was seated in the carriage with the Duchess who was regarding her critically. The child was smiling at the people who were cheering her and looking decidedly complacent. Yes, that was the word. Indeed, she was getting out of hand and it would have to be stopped.

‘Mamma, when I open the pier …’

‘We are opening the pier.’

‘Oh,’ said Victoria, and stopped herself saying more. She had heard that the pier was to be opened by the Princess Victoria; there had been no mention of the Duchess of Kent.

‘You must not imagine,’ went on the Duchess, ‘that the people are cheering you.’

Victoria, who must have the truth at all costs, said: ‘But, Mamma, they call my name.’

‘It is the Crown they are saluting.’

‘But that is Uncle William’s.’

‘You’re in a most perverse mood, and I must warn you against arrogance.’

‘But I don’t feel arrogant … only pleased that the people are so loyal and seem to like me.’

‘You think that because you are arrogant. You seem to forget that they are cheering me as well as you. And the Princes and … er … the rest of the party.’

‘But they say Victoria,’ said the Princess stubbornly.

‘Really, you are becoming most difficult.’

The carriage had stopped at the pier and the Mayor was waiting to greet them. The Duchess was helped from the carriage, followed by Victoria, and there was the Mayor seeming not to see the Duchess and going straight to Victoria all smiles, followed by the town Councillors.

‘Long live the Princess!’ called someone in the crowd. ‘Long live our little Princess Victoria.’

The Duchess might have been one of the Princess’s ladies-in-waiting for all the attention they paid to her. They hadn’t a thought beyond Victoria. It was preposterous.

She waved an imperious hand at the Mayor.

‘I have decided,’ she said, ‘that my daughter shall not open the pier. I will do it myself.’

The Mayor and his astounded councillors stared at her unable to hide their dismay. The Princess stood very still; her face had turned pale; there was glitter in her eyes, but she was determined that no one should know of the sudden fury which had seized her.

‘Your Grace,’ stammered the Mayor, ‘the people are gathered to see the Princess perform this ceremony.’

‘Then they will see me perform it instead.’

‘But the people …’

‘Come,’ said the Duchess, ‘let us proceed with the affair. Our time is limited, you know.’

In silence the ceremony was performed. Victoria could not believe that Mamma would so humiliate her in public; but she knew that the Mayor and all those present were as angry with the Duchess as she was.

Sir John, watching, thought it a mistake; but he shrugged his shoulders; nothing could alter Victoria’s accession and the more cowed she was the easier she would be to handle.

There was to be a luncheon to follow the ceremony and the Duchess coolly said that she would be unable to attend this. As the ceremony had taken place in Southampton and she was staying in the Isle of Wight it had been necessary to cross the water and that had not agreed with her. Therefore she did not feel she could take luncheon. ‘Perhaps the Princess …’ began the unfortunate Mayor. ‘The Princess cannot attend ceremonies without her mother,’ said the Duchess coldly.

It was a disastrous occasion. It would be talked of, written of, and Victoria was heartily ashamed.

Mamma had spoilt this wonderful time they were having; as long as she lived she would remember the humiliation of being treated like a child in public.

A voice inside her said: ‘You hate Mamma. You know you do. Why not admit it?’

But she had sworn to be good and good people did not hate their Mammas. At least they silenced little voices within them that insisted that they did.

The Duchess was in a bad temper which was not improved when they returned to Norris Castle and found a letter from Earl Grey. There was a new regulation regarding salutes to royal people. In future the Royal Standard must only be saluted when the King and Queen were in residence.

What a sad day, thought Victoria. Her cousins were leaving.

They were still in the Isle of Wight and she loved the place but it would not be the same without them. How I shall miss dear Ernest and even dearer Alexander! she sighed. How sad that they must go! But they had stayed for about a month and it had seemed like a week. Such fun they had had! She could not wait to write in her Journal:‘They were so amiable and pleasant … they were always satisfied, always good-humoured. Alexander took such care of me getting in and out of the boat; so did Ernest. They talked about such interesting things … We shall miss them at breakfast, at luncheon, at dinner, riding, sailing, driving, walking, in fact everywhere.’

But one must say good-bye quietly and whisper to dear Alexander – and Ernest – ‘Please come and see us again soon.’

Alexander looked at her with longing in his eyes and said he would not be happy again until he did.

And so the visit of the Württemberg cousins came to an end and she missed them sadly.

But she seemed much older than she had before they arrived. That month had changed her. She wanted the society of amusing young people; and although she tried not to, sometimes she thought of Mamma in a manner which shocked her because she was sure it was not good to dislike one’s own mother.

Chapter XIII

THE BEAUTIFUL BLIND BOY

The King and Queen were at Kew and this was a very sad occasion – a farewell dinner to the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland and their son.

The King was subdued; he was a family man and all the resentment he had previously felt towards his brother Cumberland was now suppressed because of this terrible tragedy which had overcome him and his Duchess.

‘Their only son,’ he said to Adelaide. ‘I feel for them.’

‘Oh, William,’ replied the tender-hearted Adelaide, ‘if only I could believe that this Baron Graefe could do something for the boy!’

‘We can only hope he will. They say he’s a clever fellow; and he didn’t do badly with Ernest.’

‘But Ernest lost his eye. He couldn’t save that.’

‘No. Well, we’ll see. We’ve got to speed them on their way and hope, that’s all, my dear.’

‘Poor Frederica. This has changed her.’

‘For the better,’ said William bluntly. ‘I always wondered whether she had a hand in murdering those husbands of hers.’

‘There are always rumours,’ said Adelaide sadly. ‘Few of us escape.’ She was thinking of Earl Howe, still attached to the Household but no longer in the position of Chamberlain.

‘H’m,’ said the King. ‘And there have been some particularly nasty ones surrounding my brother Cumberland and his wife.’

‘The whole world is sorry for him now,’ said Adelaide. ‘But we must go to greet our guests, I shall feel like weeping when I see dear George.’

But she managed to smile when Frederica came towards her leading her poor blind son.

‘My dear, dear George,’ said Adelaide, and kissed him tenderly.

‘Why, Aunt Adelaide, it is good of you to ask us to say goodbye to you before we leave for Germany.’

He was smiling. He had grown beautiful in his blindness; the gentleness had increased and his smile was very sweet. Adelaide had heard him referred to as the ‘Beautiful Blind Boy.’ Dear George, so young and yet to have acquired this special and so admirable quality which enabled him to bear his affliction more easily, it seemed, than those about him.

‘Here is the King, dearest,’ said Frederica.

And George turned to William, who, the tears rising to his eyes and his face growing redder than usual, embraced him warmly.

‘Dear nephew, this German fellow is good … the best in the world.’

‘So they tell me, Uncle William.’

‘You’ll be back … right as rain.’

Adelaide had taken his arm. ‘Come, dear George, we will go into dinner.’

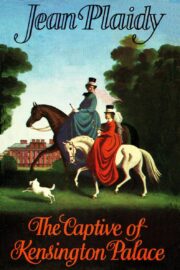

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.