‘I think Victoria is tired,’ said the Duchess.

‘Oh no, Mamma, I …’

‘You are longing for your bed, I know.’

‘Indeed not, Mamma. Why, at Chatsworth I was up until nearly twelve. Do you remember … the night of the charade …’

‘This,’ said the Duchess, ‘is not Chatsworth.’ She signed to one of her women. ‘Pray send for Lehzen.’

Lehzen arrived. She must have been waiting outside. She was never far away from Victoria.

‘Pray conduct the Princess to her room,’ said the Duchess. ‘It has been such a long, tiring day.’

Victoria said good night to Lord Liverpool, the Conroy girls and their father and to the Princess Sophia.

The Princess kissed her warmly. ‘Don’t you worry,’ she whispered. ‘The King will not blame you.’

‘I know, Aunt Sophia,’ she whispered back and then was ashamed because it was as though she were in a conspiracy against Mamma.

When she was in her bed she saw that it was only a quarter to nine.

She lay still watching Lehzen working on her sewing close to the candelabrum.

She felt angry. I am so tired of being treated like a child, she told herself. But let them wait …

Almost as soon as they reached home Christmas was with them and there was the excitement of buying and making Christmas presents and all the secrecy that went with it. Victoria was making a white bag for the Duchess under Lehzen’s guidance and it added a thrill to the days to have to thrust it out of sight whenever her mother approached. For Lehzen she was making a pin-cushion in white and gold which was very very pretty; and she had bought a pin with two gold hearts attached to it with which to ornament it. She knew that Lehzen would love it because the hearts were symbolic – hers and Lehzen’s. She believed she loved dear Lehzen best in the world next to Uncle Leopold and of course … Mamma. She believed she would love Aunt Adelaide if she were allowed to see her. Oh dear, now she was feeling angry again which one must not do at Christmas time.

Sir John, however, was behaving in a much more likeable way. For instance, a few days before Christmas Eve he came into the room where she was sewing with Lehzen and Flora Hastings looking excited and conspiratorial.

‘I want to share a secret with you,’ he told Victoria; and she could not help being excited at the thought of sharing a secret – even with Sir John.

He was carrying a little basket. ‘It is a present,’ he told her, ‘for the Duchess.’ And lifting the lid he disclosed a little dog.

Victoria cried out with pleasure. She loved animals and in particular dogs and horses.

‘But he is beautiful,’ she cried.

‘She,’ corrected Sir John, ‘is a present for the Duchess.’

‘Mamma will be delighted.’

‘I thought she would be. But I have to keep the little creature in hiding until Christmas Eve and I thought I would tell you of her existence just in case you discovered it. So …’ Sir John put his fingers to his lips.

Victoria, with a laugh, did the same.

‘What is her name?’

‘She hasn’t got one at the moment. Doubtless the Duchess will give her one.’

‘Oh, but you should say “This is …” whatever her name is. Everyone should have a name and the poor little mite can’t be nameless until Christmas.’

‘The Princess has spoken,’ said Sir John raising his eyes to the ceiling with one of those expressions Victoria disliked; but she was too excited about the dog to notice it now.

She thought: How I should love the darling to be named after me! But of course Mamma would never allow that because it would be undignified. She looked at Lehzen. Louise. No, that was not very suitable for a dog. But Flora …

‘I think Flora should be her name. You would not mind Lady Flora, if this dear little dog had the same name as you?’

Lady Flora, the most acquiescent of ladies, said that she would have no objection.

‘I name you … Flora,’ said Sir John in sepulchral tones like a Bishop at the christening of a royal infant which made Victoria laugh aloud. Sir John was studying her closely and looking rather pleased with himself.

When he had gone and Lehzen was restored to that equanimity which the presence of Sir John always seemed to destroy, Victoria said: ‘I have an idea. Besides her bag Mamma shall have a collar and a steel chain for Flora.’

Christmas Eve was the day for giving presents and the Duchess, like the Queen, liked to practise the German custom of decorating the rooms with fir trees. Victoria had found it difficult to get through the day because presents were given in the evening after dinner which as usual was taken with the Conroy family.

Afterwards the Duchess took them all to her drawing-room and there Victoria cried out with pleasure. There were two big tables and one or two little ones on all of which were fir trees hung with lighted candles and little sweetmeat favours in the form of animals and hearts and all kinds of shapes, and which Victoria knew to be delicious; and best of all piled under the trees were the presents. One of the big tables was entirely Victoria’s, the other was for the Conroy family.

What joy! thought Victoria. Mamma’s presents must be opened first. A lovely cloak lined with fur and a pink satin dress.

‘Oh, Mamma, but how lovely!’

The Duchess allowed herself to be embraced and forgot to remind Victoria of her rank in the excitement of the moment. And that was not all. Mamma had worked with her own hands a lovely pink bag the same colour as the dress; and there was an opal brooch and ear-rings.

‘What lovely … lovely presents.’

‘Open the others,’ said Mamma. She did. Lehzen’s first because dear Lehzen was there and she was determined to love whatever Lehzen gave her. A music book! ‘Oh, Lehzen, just what I wanted.’ More embraces and emotion. The tears come too easily, thought the Duchess. That must be curbed. Just like her father’s side of the family.

The Princess Sophia had embroidered a dress for her and from Aunt Mary Gloucester there were amethyst ear-rings; Sir John gave her a lovely silver brush and Victoire a white bag which she herself had made.

What lovely presents – and she knew that there would be more to come. But perhaps watching the other people open theirs was equally delightful.

And Mamma was kissing little Flora and loving her already and lifting her grateful eyes to Sir John.

Anyone would love Flora, thought Victoria; but perhaps Mamma would love her especially because she was a present from Sir John?

What a happy time was Christmas – more exciting really than travelling. And when Christmas was over, she thought, it will soon be the New Year, and in May she would have another birthday.

She was growing up.

Chapter XI

A BIRTHDAY BALL

The Queen sat beside the bedside of her niece Louise, Princess of Saxe-Weimar, and tried to persuade herself that the child was not dying.

This was the girl whom she had looked on as her own, who had done so much to comfort her when she had despaired of having children. Of all the young people whom she had gathered about her it was Louise and George Cambridge who had seemed most like her own; they had lived with her; she had mothered them both because their parents were far away; she still had George, but how long would Louise remain with her?

She had spoken to the doctors, begging them to tell her the truth, so she knew the worst. It was to be expected, they warned her. Louise had always been an invalid and now the end was in sight.

‘My dear child,’ whispered Adelaide; and Louise could only look at her with loving eyes mutely thanking her for all the kindness she had received from her.

‘Is there anything you want, darling?’

Louise’s lips moved and Adelaide bent over her. ‘Only that you stay near me, Aunt Adelaide.’

‘I shall be here, my dearest.’

Louise smiled serenely and Adelaide sat silent while the tears gathered in her eyes and began to brim over.

She was buried at Windsor and Adelaide wrote sorrowfully to her sister Ida; but Ida had her own busy life and other children to comfort her. In any case Louise had always been more Adelaide’s child than Ida’s.

There was no point in brooding over the death of this dear child. There were the living to think of and Adelaide went to see the Duchess of Cumberland who was facing another tragedy.

‘Oh, my dear Frederica, how is dearest George?’ she asked.

Frederica shook her head. ‘His sight seems to grow more dim each day.’

‘And George himself?’

‘It seems so strange but he bears it all with such fortitude. He comforts me, Adelaide.’

‘Dear child!’

‘Yes, he bids me not to fret. He says his sight will come back.’

‘That this should have happened,’ sighed Adelaide. ‘It seems such a short time ago that he was playing with Louise. He was always so gentle with her … more gentle, I think, than any of the others, though my dear George is such a good, kind boy.’

‘He was too good,’ said Frederica almost angrily.

‘And Ernest? How is Ernest taking it?’

‘As he takes everything. He believes the boy will recover his sight.’

‘And the doctors?’

‘You know what doctors are. But, Adelaide, I am thinking of taking him to see Baron Graefe. I believe him to be the best eye specialist in the world. You know he operated on Ernest most successfully. I am sure he could do something for George.’

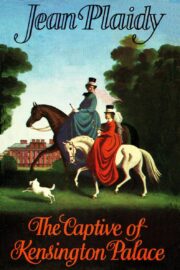

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.