Oh yes, it appeared to be a very good marriage. Louise of Orleans, daughter of Louis Philippe. She would be the Queen of the Belgians now. And Victoria hoped she would be worthy of dearest Uncle Leopold – although she gravely doubted that anyone could be that.

That was August 9th; and she would always remember it as Uncle Leopold’s wedding day.

Her feelings had changed little, for she and her uncle still exchanged loving letters. She was longing to meet her new Aunt and she felt that she was going to love her because Uncle Leopold did.

Well, they had travelled through Wales and been much fêted, but her pleasure had been marred by the sad news about George Cumberland. Poor George! There were grave fears that he would go blind and his Mamma was frantic about it and was talking about taking him to Germany for an operation.

‘How I should love to go and see him,’ she had said. ‘I should like to tell him that I am thinking of him. I should like to send him flowers every day which I would pick myself.’

‘What nonsense!’ Mamma had said. ‘My dear child, don’t you realise yet that everything you do is significant. As the future Queen you cannot send flowers to boys. In any case it would only arouse hopes which could never come to anything.’

‘I only want him to know how sorry I am, Mamma, about his eyes.’

‘It’s a judgment,’ said Mamma piously, and obscurely as far as Victoria was concerned.

But she did think of poor George Cumberland often, and she would shut her eyes and wonder what it was like not to be able to see at all.

It was now eight o’clock and time to get up. So she did and by nine she was seated at a table in a room overlooking the park where she breakfasted in the company of Lehzen. She studied the room, for she would have to describe it in her Journal. She wished she could make a sketch of it, but Lehzen sitting there with that rather anxious look on her face would be far more interesting to sketch than any room. Why was Lehzen anxious? Was she worried about something Victoria had done, or was it Mamma and Sir John – for she was sure Lehzen did worry about them – or was it because of the royal salutes and all the ceremonies which Mamma and Sir John insisted on and of which the King had expressed his disapproval?

She studied the ceiling painted with figures to represent some mythology, she did not know which, nor would she ask Lehzen for it would only provoke a lecture. The things she really wanted to know were not told her. So she remarked that it was a splendid room and it was a magnificent carpet and the waterfall she could see in the grounds was very lovely. All of which seemed the right sort of conversation to satisfy Lehzen.

‘It is a very fine house,’ she said.

‘It is reckoned one of the finest in the country,’ remarked Lehzen.

‘Finer than Kensington Palace,’ commented Victoria.

‘Later in the morning you will be taken on a tour of the house. Lord and Lady Cavendish are making up a party.’

‘That,’ said Victoria, ‘will amuse me very much.’

And it did and gave her plenty to write about in the Journal; and when they were in the grounds the Duke of Devonshire, who was walking beside her, said: ‘I wonder whether Your Highness would honour us by planting a tree in the grounds.’

‘Oh, I should like that.’

‘I will ask her Grace if you may do so.’

‘But I will do so.’

Oh dear, what had made her say that! She was pink with mortification, for what if Mamma should say ‘No’ and she have to break her word.

But Mamma was already approaching, accompanied by Lord and Lady Cavendish. ‘Victoria,’ she said, ‘you are to plant an oak and I a Spanish chestnut.’ So it was all right.

They planted their trees and she wondered what the world would be like when hers became a great tree; and what fun it would be to come to Chatsworth now and then and examine its progress.

Mamma was in a good mood because she too had planted a tree. Victoria had noticed that although Mamma wanted all possible honours for her daughter she was always a little cross if they were not extended to herself. What Mamma really wanted was Uncle William to die so that Victoria could be a Queen who had no authority. Then Mamma could be Regent. Oh dear, she was becoming very critical of Mamma who, as she was so fond of telling her, had done everything for her.

After luncheon there was a visit to Haddon Hall – a fascinating old house which dated back to the twelfth century; and afterwards they returned to Chatsworth where the Devonshires and their friends had devised a charade for the royal visitors.

Lehzen said: ‘The Duchess tells me that you may be allowed to sit up for the charade.’

‘Oh, that will be wonderful!’

‘It is really,’ went on Lehzen, ‘not to disappoint the Devonshires.’

‘It makes me very happy to know that they would be disappointed if I were not there.’

‘It is not to be taken as a precedent,’ Lehzen warned.

No! thought Victoria. But I am getting older and when I am of age I shall not be told when I must go to bed either by Lehzen, Sir John Conroy or even Mamma.

It was ten o’clock when the charade began. Victoria was seated beside Mamma and chairs were ranged all round them. Most of the candles were put out and the few remaining ones gave only a glimmer of light. Victoria was very excited. She looked at Victoire Conroy who always shared everything and on this occasion she was glad because they would be able to discuss the charade together afterwards.

‘It is to be in three syllables,’ said Mamma, ‘and there will be four acts. In the last, you must listen for the whole word.’

‘I shall, Mamma.’

This, she thought, is the sort of party Aunt Adelaide gives. How I should love to go to them. And once again the resentment towards Mamma was making itself felt. But she must give her entire attention to the charade if she were going to discover the word.

The first act was a scene from Bluebeard. How exciting! And then there was one depicting a scene at the Nile, and after that a scene from Tom Thumb. Best of all was the last act in which Queen Elizabeth figured with the Earl of Leicester and Amy Robsart. Victoria was excited because she guessed the word which was Kenilworth; and there they were in costumes similar to those her dolls had worn. She became so excited that the Duchess laid a restraining hand on her arm.

‘Pray, child, you forget yourself,’ she whispered in a shocked voice; and for a moment that resentment flared up again.

Mamma disapproved. Victoria would hear more of this, and she would have to be taught to remember her dignity in all circumstances.

Victoria noticed with glee that it was nearly twelve o’clock before she went to bed.

After Chatsworth there were many other country houses to be visited, but the weather was changing. Autumn had come and soon travelling would be impossible. Already they had suffered from heavy rainfall and there had been too much mud on the road. They had now turned southwards and were on the return journey.

They drove through Woodstock and Oxford, where they stayed with the Earl and Countess of Abingdon in their lovely residence, Wytham Abbey. Of course they must visit Oxford and the colleges, and Mamma took most of the honours, although one great one came to Sir John who was made a Doctor of Civil Law. But everyone was delighted to see them and Victoria was very interested in Queen Elizabeth’s Latin exercise book which she had used, Lehzen pointed out, when she was thirteen years old.

It was very absorbing, but Victoria’s feelings were mixed as they came closer to London. It would be pleasant to be home again, she mused. Perhaps now that she was so travelled she would be allowed to go out more often; perhaps the next time the Queen invited her she would be permitted to accept the invitation. Thirteen was no longer so young.

And on a misty November day they came riding into Kensington. The Palace looked just the same as ever and the mist which hung about the trees in the park touched with a blue haziness moved her deeply. It was good to be home.

Lord Liverpool was there waiting to receive them and the Duchess said they should all dine together, including Victoria, which they did.

Almost before dinner was over the Princess Sophia left her apartments in the Palace to call. She embraced Victoria almost nervously. She seemed to have grown much older since they had been away. Ever since the resuscitated scandal about her illegitimate son had been the talk of the town she had grown furtive, as though she were wondering what would happen next.

She whispered to the Duchess that she had come to warn her.

‘Warn me!’ cried the Duchess imperiously. The last months of travel when she had demanded and received so many honours had made her more arrogant than ever.

‘His Majesty,’ whispered Sophia. ‘William …’

‘What of the King?’

‘He is not very pleased. He has said so often that you had no right to travel as though Victoria were already the Queen. He said he would have you remember that there is a King on the throne and the honours you insisted on are for the Sovereign alone.’

‘If,’ said the Duchess, her eyes flashing, her feathers shaking, ‘I were to borrow His Majesty’s own inelegant method of expressing himself I should say “Stuff!”’

Victoria was listening. Oh dear, so the King was angry. Mamma was wrong really. She had known that they should never have been treated as though they were the most important people in the country. Even Uncle William who, she secretly believed, was a very kind man indeed, would be angry.

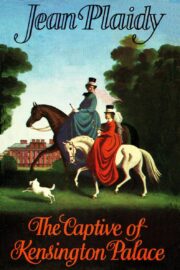

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.