What else, she asked herself, had there ever been to do?

She was not bitter; she had accepted her fate years ago when they had known that Papa would not allow them to marry if he could help it and Mamma was a tyrant and jailer at the same time. Once one of them had said: ‘I’d rather be a watercress seller down by the river or go round the streets crying sweet lavender than be a Princess of England.’ But Sophia had reminded them that if they had depended on watercress and lavender for their bread and butter they might soon have been wishing they were back in their completely boring, utterly monotonous captivity.

And now they had all escaped. Death had brought about their release. The death of Mamma, Queen Charlotte, that was, for Papa living his crazy life behind the grim walls of Windsor had ceased to be of any significance to them when he had been put away because of his madness.

George had become King … dearest of brothers, adored by all his sisters without exception; and he had given them freedom – but it had come too late.

Click-click went the steel needles – a comforting and familiar sound.

‘I wonder if dear Sir John will call on me today,’ murmured Sophia. She touched her wispy hair and sighed. Too late, she thought … everything is too late.

She closed her eyes to rest them a while. Here she lived in these rather secluded apartments in Kensington Palace and her near neighbours were Edward’s wife, the Duchess of Kent, with her dear little daughter Victoria and that pretty girl Feodora for whom they were now arranging a match. And close by in the Palace too was brother Augustus, the Duke of Sussex, with the hundreds of clocks which he tended as though they were children, his rare books and bibles and his pretty flower garden which was a source of great delight. And with him – alas for decorum – was that very merry plump little widow Cecilia Buggin. What a dreadful name – although she had not been born with it and had acquired it through marriage with a certain Sir George of Norfolk and was in fact a daughter of the Earl of Arran. Augustus was devoted to the lady and she to him, but of course he could not marry her since he considered himself married already, although the State did not recognise the marriage.

‘Oh dear,’ sighed Sophia. ‘What a mess our lives are in and all on account of our not being able to live naturally like other people. Papa’s Marriage Act has been responsible for so much discord in the family.’

But for that she supposed dearest George might be married to Maria Fitzherbert and how much happier he would have been if that union could have been recognised! It was sad now to see that dearest of brothers reduced to his present state and with that harpy Lady Conyngham perpetually at his side.

Sad indeed! A long way they had come from that time when George had been Prince of Wales, then Regent and so concerned with Mr Brummel about the cut of his coats. And how exquisite he had looked and how proud they had been of him! No woman could have loved him more than his sisters did. If George had been in power earlier how different their lives would have been! He would not have made prisoners of them; he would have helped them to marry, not prevented them from doing so.

But the girls were settled now and only she and Augusta had remained unmarried. Charlotte the eldest had married long ago and become Queen of Württemberg; Elizabeth had married the Prince of Hesse-Homburg (and how the people had jeered at her and her husband – the ageing bride and the husband who had to be bribed to take a bath); Mary had married her cousin, the Duke of Gloucester (‘Silly Billy’ in the family, although he had become a tyrant since his marriage. Mary, though, preferred a domineering husband to a demanding parent); dear Amelia – so beloved of their father – had died at the age of twenty-seven, which sorrow, some said, had sent poor Papa completely mad; that left Augusta and herself, the old maids.

‘I could not exactly call myself that,’ she said aloud. ‘And I don’t care. At least I have something to look back on.’

She looked back frequently on the great adventure of her life, on that occasion when her affairs had been talked of in hushed whispers among her sisters and how they had planned and plotted to keep her secret from Mamma.

Colonel Garth, Papa’s equerry, was not exactly a handsome man. Far from it. But it had been wonderful to be loved; and she had been really happy for the first time. She should have been more careful. But how could she be? Adventure had come to Kew and while she sat with her sisters working on her embroidery, filling her mother’s snuff-box, making sure that the dogs were walked at the appropriate times, she had dreamed of Colonel Garth and romance; and she had slipped away whenever possible, to his apartments – or he came to hers. Life had become filled with intrigue.

And the inevitable consequence!

Augusta had anxiously enquired: ‘Sophia, are you ill?’

And Mary: ‘What is wrong?’

And Augusta: ‘You had better tell.’

And there in the prim drawing-room at Kew she had whispered her secret: ‘I am going to have a child.’

‘It’s impossible,’ Augusta had said. How could an unmarried daughter of the King be pregnant? How could it possibly happen? ‘In the usual way,’ she had said defiantly, not caring very much. ‘It will send Papa mad,’ Mary had said. Anything that was alarming was always reputed to be likely to send Papa mad. ‘Mamma will be furious.’

Knowing this was true she had merely looked helplessly at them while in her heart she did not greatly care for anything but the fact that she was going to have a child.

They might have told George; he would have helped; but they did not do this. Instead the sisters had made a protective circle about her; the dear Colonel was very helpful; and so he should be since he was the child’s father. But he had been loving and tender and she was grateful. Kindly fashion had made skirts so voluminous that they might have been designed to disguise pregnancy. Dear Sophia was peaky, said Mary. She needed a little holiday by the sea.

So to the sea they went and there she gave birth to her boy who was adopted by a worthy couple; and the Colonel who had become a General doted on him and arranged his future for him and he was indeed a fine fellow now, almost thirty – a son to be proud of.

He came to Kensington to see her now and then. He knew of the relationship and was proud of it; but although brother William might openly acknowledge his ten FitzClarences borne to him by the actress Dorothy Jordan, it seemed a very different matter for a royal Princess to admit she was the mother of an illegitimate son.

‘So many scandals in the family,’ she murmured and picked up her netting. Was there another family with so many? The dear King’s life was one long scandal; her second brother Frederick, now dead, had created the biggest scandal of all when he had been accused of allowing his mistress Mary Anne Clarke to sell commissions in the Army of which he was Commander-in-Chief; then William, who had set up his house with Dorothy Jordan who had given him ten children; and Edward, Victoria’s father, who had lived with Madame de St Laurent for years (respectably it was true but without marriage lines); and Ernest, Duke of Cumberland … the less said of him the better. Many people shuddered every time they heard his name. Augustus, now living in this Palace tending his collection of clocks and bibles, accompanied everywhere by his dear friend Lady Buggin, though mild enough was scarcely without reproach; and only Adolphus in far away Hanover lived the exemplary life of a married man.

There never was a family so deep in scandal, thought Sophia.

And how strange that she should have had her share of it!

Perhaps her son would come today, by way of the back stairs. ‘Madam, a gentleman to see you.’ And they talked of course, for they knew. It was impossible to keep royal scandals secret.

My boy … my very own boy, she thought. At least I did something.

And if the boy perhaps did not come someone else would – perhaps that tall commanding gentleman whom she admired so much and was so charming and so courteous to her that he reminded her of the days when Colonel Garth had loved her so devotedly.

There was no doubt that Sir John Conroy was a very charming man. The Duchess of Kent realised this. Of course she was younger than Sophia; and beautiful too in a flamboyant way. Dear George did not think her attractive, but then he had his own views of beauty. She secretly believed he compared all women with Maria Fitzherbert. No, the Duchess was too showy and she was not of course of the same rank as a daughter of the King of England.

So it was rather pleasant sitting by the fire, dreaming of the past. I wouldn’t have had it different, she thought.

Perhaps he’ll come to see me today. And if he doesn’t, perhaps Sir John will look in.

It was comforting to have something to look forward to.

In the nursery the Princess Victoria was whispering to her dolls.

‘Darling Feodora will soon be leaving us. She is going away … to Germany to be exact and although she says we shall see each other often, I believe she says it only to comfort me.’ She shook the doll with the ruff impatiently. ‘You are not listening. You would not. You are more interested in your own affairs, I daresay.’

The wooden face stared back, as Victoria clicked her tongue and smoothed down the farthingale. This was the most glittering of the dolls and the one singled out for abuse. It was amusing to slap Queen Elizabeth now and then. ‘You may have been a good Queen,’ said Victoria now, ‘but I do not think you were a very good person.’ And dear Amy Robsart with her satin gown and ribbons was picked up and hugged to Victoria’s plump person.

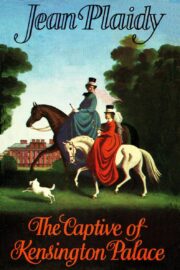

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.