‘He’s a diplomat already, then.’

‘I don’t think he thinks of her position so much. She is not without charm, you know. Such a dignified young lady. I declare that it is not right that she should be shut away there in Kensington and scarcely ever allowed any fun.’

‘Oh, that Saxe-Coburg woman!’

‘She really is trying and William is becoming incensed at the very mention of her name.’

‘I dare say the Cumberlands are hoping that their George will win the prize.’

Adelaide laughed. ‘He is a delightful boy, too. It surprises me that …’ She stopped. She had rarely been heard to make a malicious comment even about her enemies.

‘Surprise you that such parents could have such a son?’ said the forthright Ida.

‘Well, it is a little odd. And he is a charming boy. Of course if Victoria loved him I daresay there would be no objection; but we are hoping it will be his cousin.’

‘Your special protégé. Oh, Adelaide, how long ago it seems when we were together in Saxe-Meiningen wondering what would happen to us and who our husbands would be.’

‘And when the Duke of Saxe-Weimar came riding to the castle to seek his bride who was supposed to be the elder sister no one was very surprised – certainly not that elder sister – that he chose the younger.’

‘You were always the sweetest and most modest of sisters. The Duke of Saxe-Weimar was stupid. He would have been so much wiser to have chosen you.’

At which Adelaide laughed and began to talk of the baths which she thought might be beneficial for Louise. She would take her to them the next day.

‘I believe,’ said Ida, ‘that if I wanted to take her back with me you would refuse to let me do so.’

‘I would have Louise choose where she wishes to be.’

‘And you know where that is,’ laughed Ida.

It was true that Adelaide knew, and she could not help being pleased. She was born to be a mother, for her fiercest inclination was to care for children. How happy she would have been with a nursery full of them. Instead of which she had had to make do with a family of stepchildren, all of whom were now proving to be rather ungrateful. But she did have William’s grandchildren and like all young people they were devoted to her. In addition there was George Cambridge and Louise … and George Cumberland too who was constantly visiting her – and it would have been the same with Victoria if the Duchess had permitted it.

She smiled thinking of them. They took her mind off other matters; and this was a few days respite in Brighton with her dear sister, when they could talk of the days of their youth during which they had been so happy together.

It took her away from the stark reality of the uneasy days through which they were living. Revolution was a fact on the Continent and a possibility in England. Her dreams were haunted by memories of riding through the streets in her carriage and the faces of the mob leering in at her. She dreamed of the mud spattering the windows, of the stones that broke the glass. She heard their comments: ‘Go back to Germany, dowdy hausfrau.’ She knew that they called her the ‘frow’; and they whispered unpleasant things about her and Earl Howe.

She must enjoy these days in Brighton before returning to London where everyone would be thinking of and talking about that Reform Bill.

London was seething with rage. Although a strong majority had passed the Bill through the Commons, the Lords rejected it by a majority of forty-one.

Earl Grey came to see William.

‘If the Bill is not passed, Your Majesty,’ he said, ‘there will be a revolution.’

‘Bills have to pass through the Commons and the Lords and receive my signature before they become law.’

‘This one must become law,’ insisted Grey.

‘And how do you propose it should?’

‘Your Majesty must create new peers who will support it.’

‘I’ll be damned if I will,’ said the King. ‘I’m against that measure in any case. They’ll have to forget about reform.’

‘That is something I fear they will never do, Sir. The people are intent on reform and reform they’ll have.’

‘But if the Bill is thrown out …’

‘By the Lords, Sir? The Commons have passed it. Something will have to be done, and I think it would be wise if Earl Howe were dismissed from his post of Chamberlain to the Queen.’

‘Howe dismissed? The Queen will never hear of it.’

‘Nevertheless, Sir, perhaps she should be persuaded to relinquish him.’

‘Why so? Why so?’

‘He voted against the Bill.’

‘So did many others. A majority of others voted against it.’

‘But owing to Earl Howe’s position in the Queen’s household and the fact that he is on friendly terms with … er … Your Majesties …’

William was obtuse. He did not understand the reference.

Earl Grey saw that it was no use pursuing it and went back to report to his Cabinet that he had made no progress with the King.

Earl Grey discussed the King’s obstinacy with his fellow-ministers.

‘He refuses to see the implications about Howe. He refuses to create new peers. If the Lords are adamant the Bill will be thrown out. I have to make them see that this will mean revolution.’

The Cabinet insisted on the dismissal of Howe. Secrets which Grey discussed with the King were leaking out to the Tories; Howe was an ardent Tory and a sworn enemy of the Bill. The likeliest leakage would come through the Queen and as the Queen was on such terms of … er … intimacy with Earl Howe and the King was notoriously outspoken and completely lacked finesse, it seemed that Howe was the informer. No sooner had Grey discussed some matter with the King than Wellington was aware of it. The dribble of information into the opposite camp must be stemmed – and the dismissal of Howe would bring this about.

It was not difficult to work up public feeling against Earl Howe. The Queen was already loathed because she was blamed for persuading William against Reform. There were scurrilous paragraphs in the press about her. There had been criticisms for some time of her ‘spotted Majesty’, an unkind reference to her blotchy complexion; she had been accused both of dowdiness and extravagance; of Machiavellian craft and crass stupidity. But now there was Earl Howe.

There were cartoons of the Queen in the arms of her Chamberlain. In one they were embracing behind William’s back. In another they were kissing and a balloon coming from the Queen’s mouth enclosed the words, ‘Come this way, Silly Billy.’

There would be riots soon if something was not done. Grey decided something must be done and quickly; and if the King would not dismiss Howe, then Howe must resign.

He sent for Howe. He bade him be seated at his table across which he passed the cuttings from the newspapers.

‘You will see, my lord,’ said Earl Grey, ‘that it is imperative for you to resign from the Queen’s service without delay.’

Adelaide, returned from a ride, was about to change her costume when she received an urgent message from Earl Howe. When she said she would see him later, the messenger returned immediately and said that as the matter was of the utmost importance would she please see him at once.

Somewhat agitated she received him.

‘Something terrible has happened,’ she said. ‘Tell me quickly.’

He told her. ‘And I have come to return my keys to you.’

‘I shall not accept your resignation.’

He smiled at her affectionately. ‘The Prime Minister has made it very clear that I must go.’

‘But the Prime Minister does not manage my household.’

‘Your Majesty will see that in the circumstances I must resign. You, more than the King, are aware of what is going on in the streets. At times like this the people look for a scapegoat.’

‘And they have chosen you.’

‘If they had I should not be so alarmed. I would refuse to resign. I believe they have chosen Your Majesty.’

She stared at him in horror.

‘And for that reason,’ he said, ‘there have been many disgusting cartoons.’

She understood.

‘But to insist on your resignation … it is an insult.’

‘It is one we must accept. It is necessary for your safety. That is why I must insist on handing you the keys.’

She felt sick and ill. Reform or Revolution. That was what Grey thought. But Adelaide believed that Reform was Revolution.

She sat down in her chair.

‘You are feeling faint?’ asked Howe kneeling beside her.

She shook her head. ‘Please do not stay. If you were to be seen … what construction would they put on that? Please … send my women to me.’

He stood up and before he went laid the keys on the table.

The mood of the people grew more ugly. The windows of Apsley House were broken by the mob. Anyone who opposed the Bill was the enemy of the People. Effigies of the Queen were burned in public places, but the people still retained an affection for the King who continued to be represented as a foolish old man led astray by his scheming Queen. ‘Oh, I’m a poor weak old man,’ he was reputed to say in the cartoons. ‘They know I’m not able to do anything.’

Earl Grey came to the King. The Bill must be passed through the Lords. If the King would not create new peers who would support it, the Whig Ministry must resign.

‘Resign, then,’ said the King.

William sent for the Duke of Wellington and asked him to form a government. There was a menacing lull in the streets. If Wellington was at the helm with his Tories this would mean disaster for the Bill, and the people would not see the Bill thrown out. They had become obsessed by the Bill; they looked upon it as a magic formula and believed that once it was passed Utopia would be established in England; everything they had hoped for would come to pass.

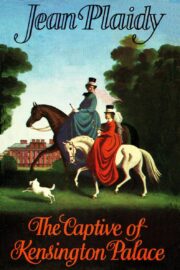

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.