‘Mind you,’ said the King, ‘I don’t care for too much ceremony, I don’t want any Bishops kissing me, and I think that we don’t want to spend too much money on the business.’

‘If it is going to please the people it should be done in appropriate style, Sir.’

‘I’ll not have money wasted,’ said the King.

The people were of course delighted at the prospect of a coronation. The disgruntled Tories said that it was a great mistake to try to economise on this, and they would not wish to attend a coronation which was tawdry and over which there had been obvious economy.

‘All right, all right,’ said the King. ‘And what do they propose to do about it?’

Wellington told him that his colleagues would not attend unless a required amount of money was lavished on the necessary details.

‘By God,’ cried the King. ‘So they’ll stay away, eh? That’s good news. It’ll avoid the crush.’

There was no way of making a King of William.

Then came trouble from the Duchess of Kent.

She wrote to the King to say that she was delighted to hear he had at last agreed to be crowned. He would, of course, wish Victoria to take her rightful place immediately behind him.

When William received this letter he was furious. He went into Adelaide’s sanctum where she was enjoying a pleasant tête-à-tête with Earl Howe.

‘That woman!’ he cried. ‘That damned woman!’

‘Is it the Duchess of Kent?’ asked Adelaide.

‘Is it the Duchess of Kent! Of course it is that damned irritating woman.’

‘What is the trouble now?’ asked Adelaide.

‘She’s giving me instructions about the coronation. Her daughter is to walk immediately behind me, to show everyone that she is second only to the King. Did you ever hear such … such … impertinence.’

‘William, my dear, I beg of you to sit down,’ said the Queen. ‘The Duchess is merely being her tiresome self.’

‘And if she thinks I’m going to have that … that chit …’

‘She is only a child. She should not be blamed.’

‘I don’t blame her. Nice little thing. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to let her mother poke her interfering finger into royal affairs. Certainly not, I say. Certainly she shall not walk immediately behind me. Every brother and sister of mine – and I’m not exactly short of them – shall take precedence over Victoria.’

‘Is that right …’ began Adelaide. ‘I mean is that the way to treat the heiress presumptive to the throne?’

‘It’s the way I am treating her,’ said the King. His lips were stubborn. ‘That child will come to the coronation and walk where she is told.’

‘Oh, it is monstrous!’ cried the Duchess. ‘If I were not so angry I should faint with fury.’

‘Pray do not do that,’ said Sir John. ‘We need all our wits to deal with this situation.’

‘Victoria shall not be exposed to indignity, which she would be if she followed those stupid old aunts and uncles of hers.’

‘She must not do it.’

‘Then how … ?’

Sir John smiled, delighted that once again the Duchess was at loggerheads with her family. The more isolated she was, the more power for Sir John. As it was he was almost constantly in her company; his home was Kensington Palace, and to give respectability to the situation, Lady Conroy and the children were there also. His daughters Jane and Victoire were the companions of the Princess Victoria and he endeavoured to arrange that she saw as little as possible of the young people of her own family. The fact that the King had said she must make more public appearances had worried him; he had had visions of Victoria’s affection for the Queen – which was already considerable – being a real stumbling block. So he welcomed controversies such as this and encouraged the Duchess in her truculent attitude.

‘If the King will not give her her rightful place,’ said Sir John, ‘she must refuse to attend the coronation.’

‘The heiress to the throne not present at the coronation!’

‘If it is regrettably necessary, yes. The people will notice her absence and they will blame the King for it. Moreover, the King wishes Victoria to be under the charge of his sisters and not to walk with you, which is significant.’

‘Significant,’ cried the Duchess.

‘It means that on this important occasion he is taking your daughter from your care. Don’t you see what meaning people will attach to this?’

‘I do indeed and my mind is made up. Victoria shall not attend the coronation.’

‘I should write and tell His Majesty that you believe you should stay in the Isle of Wight as to leave it now might be detrimental to your daughter’s health.’

The Duchess nodded sagely.

‘This will show the old fool,’ she said.

‘Let her stay away,’ growled the King. ‘I tell you this, Adelaide: my great hope is that I live long enough to prevent that woman ever becoming Regent.’

‘Of course you will. There are many years left to you.’

William’s eyes glinted. ‘God help the country if she was ever Regent. I’m going to live long enough to see Victoria stand alone.’

‘You will if you take care of yourself.’

He smiled at her, his eyes glazed with sudden sentiment. ‘You’re a good woman, Adelaide. I’m glad I was able to make a Queen of you.’

‘It’s enough that you are a very good husband to me.’

William was pleased. Momentarily he had forgotten that maddening sister-in-law of his.

It was not a very bright September morning but the crowds were already lining the streets. They chatted about the odd but not unlovable ways of the King; some murmured a little about the Queen – why must we always bring these German women into the country? – but after all it was Coronation Day and the Reform Bill had passed through the Commons and better times they believed lay ahead, so for this day they were prepared to forget their grievances.

When the King and Queen drove past on the way to Westminster Abbey a cheer went up for them. William wore his Admiral’s uniform and looked exactly like a weatherbeaten sailor which amused the crowd; and the Queen looked almost beautiful in gold gauze over white satin.

‘Good old William,’ the cry went up, and although no one cheered Adelaide there were no hostile shouts.

But where was the Princess Victoria? One of the most delightful sights at such functions was usually provided by the children and the little heiress to the throne was very popular. Her absence was immediately noticed and whispered about.

‘They say that the Duchess and the King hate each other.’

‘They say the Duchess won’t bring Victoria to Court because she is afraid of Cumberland.’

Rumours multiplied; there were always quarrels in the royal family.

Meanwhile the King and Queen had reached the Abbey and the Archbishop was presiding over the ceremony of crowning them. William who looked upon all such occasions as ‘stuff’ showed his impatience with the ceremony and so robbed it of much of its dignity; but Adelaide behaved with charming grace and many present commented on the fact that although she might not be the most beautiful of Queens she was kindly, gracious and peace-loving.

During the ceremony the rain pelted down and the wind howled along the river; however, when the royal pair emerged the rain stopped and the sun shone, so they were able to ride back in comfort through the streets to St James’s.

The people cheered. He was not such a bad old King, they decided, and if he was ready to put up with his spotted wife they would too.

William was grumbling all the way back about Victoria’s absence. It had been noticed; it had been commented on.

‘It’s time,’ he said, ‘that someone taught that woman a lesson.’

Soon after the coronation Adelaide went to Brighton with her niece Louise of Saxe-Weimar, the daughter of her sister Ida, for whom the Queen had very special love among her family of other people’s children because Louise was a cripple. Adelaide had had this child in her care for most of her life and this made her seem like her own daughter, just as George Cambridge was like her own son.

But Louise was growing weaker as the years passed and this saddened her. Louise’s mother was now paying a visit to England and to her Adelaide was able to talk of her anxieties – the state to which the country had been reduced and her fears (quoting Earl Howe) that if this dreaded Reform Bill was passed it would be the beginning of the end for the Monarchy.

Ida listened sympathetically and admitted that she was glad to be the wife of a man who was not the ruler of a great country. She was not rich and not really very important but she would not wish for Adelaide’s anxieties.

‘I had the Crown and was barren,’ said Adelaide. ‘But I have been happier than I would have believed I could possibly be … without children.’

‘You have other people’s,’ said Ida. ‘And how is the little girl at Kensington?’

‘We scarcely ever see her although William has expressly told her mother that as heiress to the throne she must appear with him in public’

‘The Saxe-Coburgs give themselves such airs. Though why they should, I can’t imagine. There was all that scandal about Louise of Saxe-Coburg. They kept very quiet about that. And I believe they are hoping that Victoria will marry one of the two boys – Ernest or Albert.’

‘William has decided that she shall have George Cambridge. He is already rather taken with her.’

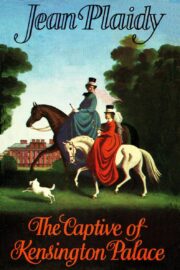

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.