‘How dare you speak so of the Princess!’

‘I will speak as I wish.’

‘You will not criticise the Princess in my hearing.’

‘My father says we should speak the truth.’

‘Do not quote your father to me.’ The Baroness had risen. Her knotting had fallen to her feet; her lips were quivering; she was angry and alarmed. One day there would be a big scandal concerning Sir John Conroy and that was going to be harmful to the dear Duchess and the even more dear Princess Victoria.

‘Why not? He is important. He could have you sent back to where you belong, you old German woman. And he will. He says he will.’

It was more than the Baroness could endure; she walked away catching the knotting string about her ankle and pulling her work along the floor as she went. Victoire broke into peals of laughter and the Baroness picked up the work, her face scarlet, her lips moving angrily as she tried to extricate herself.

When she had done so she walked away to look for the Baroness Lehzen. She was going to tell her at once what had happened and ask her advice as to what action should be taken because she was sure some action must.

The Baroness Lehzen had accompanied Victoria to the Princess Sophia’s apartments and so was not in her room.

How dared that insolent girl say what she had! She was like her father. Oh, why could not the dear Duchess see what vipers she had allowed to enter her household!

She must be made aware … Oh, why wasn’t calm levelheaded Lehzen here.

It was unfortunate for the Baroness that the Duchess of Kent should have chosen to send for her at that time. There was some matter concerning the Princess Victoria she wanted to discuss but the sight of Späth’s indignant flushed face drove the matter from her mind.

‘What has happened?’ she demanded.

‘I have just left that … that insolent child,’ spluttered Späth.

‘Insolent child?’ The Duchess knew very well to whom Späth referred and Späth should know from experience how she disliked anything connected with Sir John Conroy to be disparaged.

‘Victoire Conroy. She … she dared to criticise the Princess Victoria. She said she preferred the company of boys …’

‘I believe that to be true. Victoria is always talking of those two cousins of hers.’

‘I could not stand by while that girl made such observations about the Princess.’

‘You are being foolish again,’ said the Duchess coldly. She had never let Späth forget how stupidly she had behaved over Feodora and Augustus d’Este.

Späth’s colour deepened. ‘I am not,’ she said recklessly. ‘And there is something I have to say to Your Grace about … about yourself and Sir John Conroy.’

Späth was too excited to notice the expression on the Duchess’s face and to be aware of the ominous silence.

‘I do not forget my place …’ began Späth.

‘Do you not?’ said the Duchess sarcastically. ‘You surprise me.’

‘No, I do not forget it and I speak only out of love for Your Grace and our dear Princess.’

‘Pray continue.’

‘The Princess has noticed the … er … friendship between Your Grace and … this man.’

‘The Princess has long been aware of the friendship between myself and Sir John. Indeed, I hope she feels similarly towards one who has been such a good friend to her and the entire household.’

‘God forbid!’ cried the Baroness.

‘My dear Späth,’ said the Duchess, and her voice showed clearly that the Baroness was far from being dear to her, ‘are you mad?’

‘I am very anxious,’ went on the Baroness, ‘because the Princess has noticed that Sir John Conroy is on very familiar terms with Your Grace.’

‘How … dare you!’ cried the Duchess. ‘Pray go at once to your room. I will deal with your … impertinence later.’

The trembling Baroness left her. At least, she assured herself, I told her the truth.

The Duchess went at once to Sir John.

‘My dearest lady, what has happened?’ he asked looking up from the papers on his table.

‘That … impertinent old woman … That Baroness Späth. Oh dear, and I placed such confidence in her. She was a good nurse to Feodora and afterwards to Victoria and now … now … I will not allow her to remain here. She must go.’

Sir John smiled. He would like to be rid of the two old ladies. Lehzen more than Späth, for Späth was an old fool compared with Lehzen.

He rose and taking the Duchess’s hands kissed them. ‘Pray be seated and tell me exactly what happened.’

‘She was … insolent. She said that Victoria had noticed that you and I …’

‘What is this?’

‘That Victoria had noticed that you and I were … friends.’

‘This is … monstrous.’

‘I think so too.’

‘There is only one thing to be done.’

Sir John nodded sagely. The old fool had played right into his hands.

Chapter VI

THE BATTLE FOR LEHZEN

Adelaide was watching the King carefully; she was terrified that his exuberance would overflow and he would do something which would be considered mad. At the moment the people were lenient; he had won their approval by lacking the dignity of George IV – not that he had to cast aside what he had never had – but that royal dignity was indeed lacking and for the moment, the people liked their King. He was an old man with a red weatherbeaten face; and no one could be more homely than the Queen; but somehow they managed to convey that they wished to do their duty.

There was no doubt that William was enjoying his position. He went about among the ordinary people, shaking hands with them and patting children on the head.

When the crowds gathered round him and Adelaide feared for his safety he would cry: ‘Now, my good people, let me through, let me through. You want to see me and I want to see you. So stand back a bit and give me air.’

A very unroyal King! decided the people; but a good and kindly man eager to serve his country.

Adelaide had believed that the stay at the Pavilion would be a rest after all the ceremonies it had been necessary to attend but she was realising that little respite was to be allowed the King and Queen. It was all very well for George IV to shut himself away from his people; William IV was not going to be allowed to do this. Nor did he wish to. He was still delighted by his office and determined to enjoy it. He was homely; he was bluff; he was the sailor King. He was constantly waving ceremony aside.

‘The Queen and I are very quiet people,’ he would say. ‘She sits over her embroidery after dinner and I’ll doze and nod a bit.’

He had a talent for making the kind of remarks which could be seized on by the press and those who liked to report the eccentricities of the King. For instance when he had asked a guest to attend a ceremony the man replied that he could not do so as he did not possess the required kind of breeches. ‘Nonsense … ceremony … stuff!’ cried the King. ‘Let him come without.’ ‘Stuff’ was one of his favourite words for that etiquette which he wished to sweep away and he applied it to anything of which he did not approve.

Not only was he completely lacking in royal dignity, he was tactless in the extreme. He was constantly telling Adelaide that he did not know what he would do without her and that she was more to him than any beautiful and attractive woman could ever have been. He gave people lifts in his carriage. He shook hands affably like any visiting squire; he told the Freemasons whom he was addressing on one occasion: ‘Gentlemen, if my love for you equalled my ignorance of everything concerning you, it would indeed be unbounded.’ He behaved in every way that was unkingly; but all knew that he meant to be kind.

He had made it clear that he would not allow his brother Cumberland to dominate him as he had dominated the late King. Cumberland was deprived of his Gold Stick, told to remove his horses from the Windsor stables because the Queen needed them for her carriage, and at a dinner the King had toasted the country and glaring at his brother had added: ‘And let those who don’t like it leave it.’

As Cumberland was at the height of his unpopularity this further endeared William to his people.

He was a blundering old man, but as long as he kept his sanity, the people were pleased with him.

Adelaide, who had become very fond of him since her marriage and suffered from a terrible sense of failure because she had failed to give him an heir, grew more and more nervous. When the people became over-excited she was afraid there would be riots. She had never understood the exuberance of the English; and she was well aware that there was terrible unrest throughout the country. The affairs of France were once more in chaos; what happened in that country could happen in England, so Adelaide believed. There was one word which was constantly being used in all circles: Reform.

The people throughout the country were dissatisfied with their lot. The differences between the rich and the poor were too great. The harvest had been bad; food was dear and there was no money to buy bread. The silk weavers of Spitalfields were in revolt; the farm labourers of Kent were demanding more money; and the mill hands farther north were restive. Hay-ricks were burned down in the night; barns set on fire. Through the country men were threatening dire consequences if there were not Reform.

All this worried Adelaide.

‘Trouble?’ said William. ‘There’s always been trouble. My father was nearly assassinated several times.’

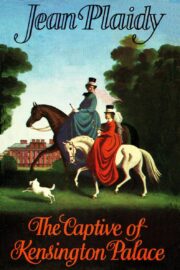

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.