‘You look pleased,’ the Duchess was saying, her voice gentle as it rarely was. ‘Has something pleasant happened?’

‘I have an invitation from Aunt Adelaide.’

How the children loved that woman! She was harmless enough, more suited to be the mother of a large family than a Queen of England – which she would be if William didn’t go mad before George IV died.

‘And you wish to accept it?’

‘May I?’

‘I believe you would be a little sad if I said no,’ smiled the Duchess.

‘Well, Mamma, I should. Aunt Adelaide’s parties are so amusing. She thinks of the most exciting things for us to do.’

‘And your cousin Cambridge – how do you like him?’

‘Very much, Mamma.’

‘I expect he misses his family.’

‘He did at first, and now Aunt Adelaide is like his mother. I think he is beginning to feel that Bushy is his home.’

The Duke said: ‘I trust she remembers that you take precedence over your Cambridge cousin.’

‘There is no precedence at Bushy, Papa. We never think of it. It’s great fun there.’

‘Well, don’t forget, son, that you come before him; and if there should be any attempt to set him ahead of you … at the table shall we say …’

‘There couldn’t be. We just sit anywhere.’

The Duke shrugged his shoulders.

‘It’s all right while they’re young,’ said the Duchess. She turned to her son. ‘So your Aunt Adelaide has written to you, not to us?’

‘She always writes to me, Mamma.’

‘It is a little odd. But that’s your Aunt Adelaide.’

He smiled and he was so beautiful when he did so that the Duchess, hard as she was, was almost moved to tears.

‘Oh yes,’ he said ‘that is Aunt Adelaide.’

‘So you want our permission to accept.’

‘Yes, Mamma.’

‘Then go along and write your letter and when you have written it bring it back and show it to me.’

He went off and left them together.

‘So,’ said the Duke, ‘he goes off to mingle with the bastidry.’

‘It’s true. But he’ll come to no harm through them. Remember William and Adelaide may well be King and Queen.’

‘That’s true enough and it does no harm for George to be on good terms with them.’

‘What will happen if William gets the Crown? What of the family of bastards?’

‘They’ll plague the life out of him, I’ll swear.’

‘William is a fool over his bastards.’

‘That’s because he can’t get a legitimate child.’

‘But we are wise to let our George go to Bushy. You can imagine what would happen if we didn’t. Adelaide would become too fond of George Cambridge and you don’t know what schemes might come into her head.’

‘Schemes? How could Adelaide scheme?’

‘It may well be that Adelaide thinks George Cambridge might make a suitable husband for Victoria. Oh, I know you don’t think she will ever grow up to need a husband, but we have to take everything into consideration. What if Adelaide makes a match between young Cambridge and Victoria? What I mean Ernest is this: Suppose Victoria does come to the throne … suppose there is no way of stopping her, then her husband should be our George, not George Cambridge.’

The Duke was silent. He could not with equanimity let himself believe that Victoria would come to the throne; but he saw the wisdom of his wife’s reasoning. Consort would be the second prize if it should prove to be impossible to achieve the first.

The Duchess went on: ‘George must accept Adelaide’s invitation. I know we are determined that – if it is humanly possible – Adelaide shall never be Queen of England, but just suppose she is. Then she will be powerful; she leads William now. What she says will be the order of the day. So … as my second string … if George can’t be King of England he shall at least be the Queen’s Consort.’ The Duke regarded his wife shrewdly. She was right of course. He was going to fight with all his might to keep Victoria off the throne but if by some evil chance she should reach it, his George should be there to share it with her. ‘Oh yes, it is well to be on good terms with Adelaide,’ he said. The Duchess nodded. They saw eye to eye. Let him have his little philander with Graves’s wife. What did it matter? What was fidelity compared with the ability to share an ambition?

It was very lonely in Kensington Palace without Feodora, but true to her word the older sister wrote regularly to the younger one and it was the delight of those days to have a letter from Feodora. Victoria read them all again and again and could picture the fairy-tale castle which was Feodora’s home. It was Gothic and seemed haunted; there were so many dark, twisted little staircases, so many tall rooms with slits of windows from which Feodora could look on Hohenlohe territory. Her husband was very kind and she was growing more and more fond of him.

‘I don’t believe she ever gives a thought to Augustus now,’ Victoria told the dolls.

She sighed. How much happier it would have been for her if that marriage had taken place. She liked calling on Uncle Sussex and gazing with awe on his collections of rare books and bibles. The clocks were amusing too, particularly when they all chimed together. Victoria especially liked the ones which played the national anthem. She always stood to attention when she heard that and thought of dearest Uncle King and the time when she had asked his band to play it for her. Dear Uncle Sussex; he really was one of the favourite uncles; and how she loved his flowers and still liked to water them, although it made her feel rather sad because darling Feodora was not sitting under the tree. But Lady Buggin was amusing and very kind and nice. It was such a pity that Mamma did not like her and that she was told to keep away when Victoria paid a visit. Victoria liked people who were affectionate and laughed a great deal; and Uncle Sussex seemed much happier when Lady Buggin was there. Uncle Sussex was very tall and he looked grand in his gold-trimmed dressing-gown which he wore a great deal in the house. His little black page was always in attendance – also grandly dressed in royal livery. Uncle Sussex treated him with respect and always called him Mr Blackman. Yes, it would have been much more comforting if Feodora had married Augustus and Uncle Sussex had become her father-in-law.

But it seemed Feodora was happy enough in her castle. She hoped, she wrote to Victoria, that before long she would be able to tell her some very exciting news. Victoria should rest assured that she should be one of the very first to hear.

‘Now I wonder what that can be,’ said Victoria to the dolls.

Lehzen was seated in the room, ever watchful; this was a little respite after her drawing lesson. Of all lessons she much preferred music and drawing. Mr Westall who was an important artist was very pleased with her; and she loved best of all sketching people. It was fun to send her drawings to Feodora – particularly those of herself which was, Feodora replied, almost like having darling Victoria with her. Mr Westall said that had she not been a young lady of such rank she might have become a distinguished artist. What praise! But when she repeated it to Lehzen that lady had smiled wryly and said: ‘But as it happens you are a young lady of rank.’

It was the same with singing. Mr Sale of the Chapel Royal was delighted with her voice. It was true and sweet, he told her; lessons with him were always a joy, as were dancing lessons with Madame Bourdin. She would have cheerfully given herself to study if this meant learning subjects like music, dancing, drawing and riding! French, German, Italian and Latin, to say nothing of English and arithmetic, were less inviting; but because she was so much aware of her vague importance – which was never exactly mentioned but constantly implied – she did her best; and the Rev. George Davys who was in charge of her general instruction was pleased with her.

Victoria had been called a little vixen by some; she admitted to waywardness and storms; but at heart she was determined to do her duty however unpleasant this might be and always she was aware of the watching eye of Lehzen, and the effect her failure would have on dear Uncle Leopold. Mamma too, but it did not hurt in the same way to disappoint Mamma. Indeed there were times when some perverse little spirit rose in her and she felt a desire to plague Mamma. But the thought of losing Lehzen’s approval or saddening Uncle Leopold always sobered her.

Lehzen came over and said that it was time for their walk.

‘Do you know what I wish to do today, Lehzen?’ said Victoria. ‘I am going to buy the doll.’

‘You have the money?’

‘Yes. I have now saved enough.’ She thought of the doll. It was as beautiful as the Big Doll which Aunt Adelaide had given her; in fact it bore some resemblance to it and would be a pleasant companion for the Big Doll. As soon as she had seen it she had wanted it. She had pointed it out to Lehzen in the shop window and Lehzen had reported her desire to the Duchess. Together they had decided that it was not good for Victoria to have all she wanted; she must therefore save up her pocket money until she had enough to buy the doll. It was six shillings – a high price for a doll, but then it was a very special one.

‘Is she not growing a little old for dolls?’ wondered the Duchess.

Lehzen could not bear that she should, so she remarked that she thought there was no harm in her fondness for them … for a year or so. Many of the dolls represented historical characters and it was amazing how quickly she learned the history of those who were in the doll family.

So it was decided that she should save for the doll and add this one to her collection. The owner of the shop, although he had left it in his window, had put a little notice on it to say Sold. Every time she passed Victoria gazed longingly at the doll and exulted over the little ticket; and gradually she was accumulating the money.

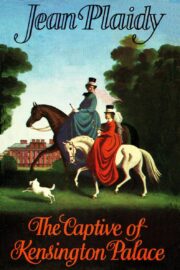

"The Captive of Kensington Palace" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Captive of Kensington Palace" друзьям в соцсетях.