The porter closed the gate behind Leblanc. What could one say? Only the truth. Madame would send her to play the innocent in some respectable school in Dresden. To live among giggling schoolgirls. To pretend to be heedless and wholesome. “I have not been a young girl for a long time.”

“Child . . .”

“There are roles even I cannot play.”

Perhaps Madame sighed. “We will speak of this again. Are you ready for tonight?”

It was a relief to turn to practical matters. “All is arranged. Every detail.” Her gun was cleaned and loaded and her clothing set out, upstairs. She had tied together the last strings of her plan this afternoon. “I will free the children. La Flèche has promised to take them onward. We will use the freight barge at the Jardin des Plantes and slide downriver at dawn. The Cachés will be to the coast within a week.”

“That is well done.”

“It will be the last great operation of La Flèche, I think, now that Marguerite will depart from France tomorrow. She was not only their mastermind. She was their heart. I do not think they will carry on without her.”

La Flèche was the best of the several secret rescue organizations—clever, well organized and reliable. Hundreds of miserable souls, fleeing the guillotine, owed their lives to La Flèche. She knew them well, having spied upon them and reported all their stratagems to Madame. The Police Secrète found many uses for an organization that smuggled men into England. “I will miss spying on them. Marguerite de Fleurignac throws herself away on the Englishman Doyle. This business of falling in love is a great stupidity.”

“And yet, I believe she will be a happy woman in England, with her large English spy. And still useful to France. She will doubtless give refuge to the Cachés you free, once they are across the Channel.”

“Nothing is more certain. She would care for every child in the world if she could reach her arms around them. She leaves Paris soon. Perhaps tomorrow. Citoyen Doyle will see to that.”

“These new husbands . . .” Madame smiled.

“He is very protective.” The English spy Doyle was like a great mastiff. He was a formidable enemy, but what he took under his protection was safe for all time. “He calls her Maggie, you know. I suppose she will become used to it.”

“And the boy Hawker?”

She had to smile. “He is mine.”

Madame bowed her head with a touch of mockery. “I congratulate you. Even the English are not sure he is theirs.”

“For the space of one night, he is mine.” In the midst of many troubles, amusement filled her. “Oh, I have been Machiavellian. You would have been so proud of me. I did not argue passionately. I showed him the barbarity of that place and told him what was planned. He will not permit it.”

“You trust your judgment of him? He has killed men, my child. He has a reputation for cold-bloodedness.”

“It is deserved. But he has weaknesses, as all men do. I watched him carefully. He is driven by his curiosity. And, most especially, he does not like to see women hurt. I took care he should see one of the girls being mistreated upon the fighting field. Now he is tied to my cause.”

“That was astute.”

The praise filled her with warmth. “One may hang many hopes upon the hook of a single small decency.”

“Do not forget he is an enemy, Justine.”

“He is a most useful enemy.” In all of France, she could have found no more perfect associate. There was a core of honor in him, though he would have denied it vehemently. Once he was committed, he would not turn back. “I will use that ruthlessness of his.”

She ran plans through her mind, as a woman might run a strand of pearls through her fingers, every pearl familiar in shape and texture. “If we are caught, I will see the blame falls upon him and the English. Everything works out perfectly.”

Eight

BY THE TIME JUSTINE RETURNED TO THE KITCHEN, Séverine had left.

“It is too hot. She has gone to play in the loft.” Babette waved to the kitchen window, toward the stable and the shed behind it. She was brushing a dozen wide, fluted circles of pastry with egg yolk, using a little brush made of feathers, making progress with the tartes now that she had less assistance.

Justine had not eaten, so she stole an apple from the big bowl and dodged away from Babette’s scolding, out to the stable yard behind the brothel.

The yard was kept in the most perfect order and cleanliness. Madame said—she was very practical—that men would expect to find clean girls in a clean house. Jean le Gros worked in front of the stable door, currying one of the coach horses, keeping an eye on everything. When she walked by eating her apple, he called, “La petite is off that way,” pointing to the shed, and, “That pig-faced piece of dung is gone.” No harm would come to Séverine while Jean watched.

The storage shed hugged the back of the stable and held all things that were outworn but not yet useless enough to throw away. The loft above the shed was a considerably more interesting place. It was a very secret place, that loft. Hard-eyed men—and some women—came to shelter for a night or two and left under the cover of dark, carrying messages. Some were agents of the Police Secrète. Some were Madame’s own couriers, loyal only to her. Many were sent here by La Flèche.

That had been her own particular work for La Flèche—hiding those who must flee France, taking them onward to the next link in the chain that would lead them to safety. Under Madame’s orders, she had become a trusted member of the great smuggling organization. That was a noble work in itself, of course. It was also useful to the Secret Police to have an agent within those counsels.

When the loft was not occupied by desperate people, this was Séverine’s playhouse.

The door to the storage shed was left open, always, as if nothing of importance happened here. The main room was dull and innocent. She picked her way between feed bags and wooden boxes. A ladder slanted up to the open square in the ceiling. She bit strongly into the apple, held it with her teeth, and climbed the ladder to emerge through the opening of the trapdoor.

A path was cleared the whole length of the loft, from the small window at one end to the large window at the other. Lumber, broken furniture, shelves of old dishes, crates, barrels, and piles of moth-eaten blankets jostled together on both sides.

In the relatively empty space below the window, where fugitives made rough beds of straw and blankets, Séverine had invited her favorite doll and a subsidiary doll to take luncheon upon a square handkerchief spread upon the floor. They were eating pieces of bread, small stones, and leaves from the chestnut tree, served on cracked plates.

“You have come, Justine. I am so happy. We are having dinner, Belle-Marie and her friend and I. Here.” She patted the boards imperiously. “I will share my bread with you.”

“I am just in time, then.” She pulled herself the last steps into the loft. “I am famished, you know. My morning was busy.” She came and sat and composed her skirts around her. It was not necessary to eat the somewhat dusty bread, only to raise it to her mouth and pretend to eat. “That is very good. You may finish this apple. I stole it from Babette.”

“We will pretend Babette is a giant and you have stolen the apple from her castle.”

“That is exactly what I did. I am too clever for any giant. I always escape with their treasure.”

“You are immensely brave.” Séverine took a bite of apple and held it to Belle-Marie, who presumably ate some.

“Belle-Marie is looking fashionable today.” The doll wore a little cap with real lace. One of the women of the house was skilled with a needle and had made that cap, and also the apron and the blue dress. Justine accepted the apple from Séverine and took a bite and offered it back.

“It is Théodore’s turn now,” Séverine said.

Théodore had been carved from a bit of thick board and wrapped in red cloth. His arms and legs were nailed on and could move. “Perhaps he does not like apples.”

Séverine giggled. “Of course he does. Jean le Gros made him for me.”

That was enough of an explanation, she supposed. There was a crude face carved on Théodore and a fine big mustache drawn on in ink. “He is a soldier,” Séverine said. “He is Belle-Marie’s particular friend.”

So Théodore got his bite of apple. Séverine was content to finish the rest of it. The dolls, after all, had their lovely plates of round white stones.

Séverine had opened the windows at both ends of the loft. It could not be said to be cool, but a little breeze found its way here, often enough. The loft was shaded by the height of the stable. It was as comfortable a place as any to pass the heat of the afternoon.

Under the disorder and the deliberately cultivated dust, this was a place of refuge. One could rest here . . . and she was very tired. This last week, her days had been filled with schemes and excitements and work that must be done. Robespierre had fallen. The government had changed. There had been a small amount of riot and fighting. She had been soaked in the rain, not once but twice, and had run the length of Paris a dozen times arranging small matters with huge consequences. She could not remember when she had last slept.

She said, “I must work tonight. I’m sorry.”

“It is all right. Babette lets me sleep in her room, you know. She is teaching me to knit. I am making a shawl for Madame, but that is a secret you must not tell anyone.”

“I will be as silent as soup.”

“You are very silly. Soup is not silent. Soup goes . . .” and Séverine made a slurping sound.

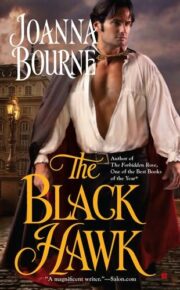

"The Black Hawk" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Black Hawk". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Black Hawk" друзьям в соцсетях.