"What's wrong, Gabrielle?" she asked quickly.

"I swallowed too fast, Mama."

"Well, take your time, honey. You got all the time in the world. Don't rush your life like I did. Think twice and then think twice more before you say yes to anything. No matter how simple or small it seems."

"Yes, Mama."

The music had stopped.

"I'm going to wind it up again," Mama said. "Tonight I just feel like hearing music. Tonight I don't want to hear silence."

I watched her get up and go to the Victrola. I hated being deceitful to her, but she was so down, so depressed and alone, I could never add even a pinch of sadness to her misery. I lowered my eyes to my food. After I ate, I helped clean up and then went upstairs to finish sewing my graduation dress. Mama had cut out the pattern. She went out on the galerie to-weave some split-oak baskets, but she wasn't out there long before Mr. LaFourche came to fetch her in his Ford pickup truck. His wife was having terrible stomach cramps.

"I got to go make a visit," she called up to me. "You be all right?"

"Yes, Mama. I'm fine."

"If that no-account father of yours shows up, don't give him anything to eat," she said.

"I won't, Mama," I said, but she knew I would. After I heard the truck leave, I came out of the loom room and put on my dress. I went to Mama's mirror again and gazed at myself in the light of the butane lamp. The dress fit perfectly. I thought it made me look years older.

But I didn't smile at my image.

I didn't feel my heart burst with joy and excitement.

I began to cry. I sobbed so hard, my stomach ached. And then I ran out of tears and sat silently on my bed, staring through the window at the sliver of moon above the willow trees. I sighed deeply, took off my graduation dress, put on my nightgown, and crawled under my blanket.

When I closed my eyes, Mr. Tate's face with his lustful smile appeared. I moaned and sat up quickly, my heart pounding. How would he sleep tonight? I wondered. Was it easier for him to put the sinful act out of mind than it was for me, or would his conscience come roaring down over him and drive him to his knees to pray for forgiveness?

I was very angry. I wanted to pray to God to refuse him. I wished him centuries of pain and suffering. I hoped that when he had left my pond, he had fallen out of his canoe and been attacked by snakes and alligators. His cries would be music to my ears. I raged for a while like this and then I felt guilty for doing so and shut down my vengeful thoughts.

But Mr. Tate had stolen more than my youth and innocence when he had attacked me, he had invaded and stained my private world. My sadness was deeper because of that. I was afraid of what it meant, for before this, I never felt alone. No matter that I had no real friends; no matter that I wasn't invited to parties and did not go to dances and shows.

But if I lose my world, I thought, if I lose the swamp and the animals, the fish and the birds, the flowers and the trees, if I fear the twilight and cringe when shadows fall, where will I go? What will become of me?

Would the beautiful blue heron return to her nest above the pond?

I was afraid of the morning, afraid of the answers that would come up with the sun.

2

Paradise Lost

I was positive that Daddy's not coming home all night was the only thing that kept Mama from noticing that something serious was bothering me the next morning. Mama had been out late treating Mrs. LaFourche, who Mama believed had eaten a few bad shrimp, so Mama was pretty tired and irritable anyway. She rose, expecting to find Daddy either sprawled out on the front galerie or on the floor of our living room, but he was nowhere to be seen.

Mama didn't notice that I ate very little breakfast or that I was quiet and tired myself. I had tossed and turned, flitting in and out of nightmares most of the night. But Mama ranted and raved to herself, raking up old complaints about Daddy, criticizing not only his excessive drinking and gambling, but his laziness.

"All the Landrys were lazy," she lectured, returning to an old theme. "It's in their blood. I should have know'd what your father would be like right from the start. Oh, he charmed me in the beginning by building this house and working hard for a while, but he was only setting me up the way the Landry men always set up their women, so he could throw it back at me all the time about just how much he done for me already.

"Like being a husband and a father was a nine-to-five job," she complained. "But being a mother and a wife was a twenty-four-hour, seven-day-a-week job. That's the way the Landry men see it.

"Before you marry anyone, Gabrielle, you ask to see his grandpère, and if his grandmère's still living, you talk to her and get the lowdown, hear?" she warned.

"Yes, Mama."

She finally took note of me, but she attributed other reasons to my appearance.

"Look at you," she remarked, "nervous as a just-hatched chicken with your graduation just a day away now."

"I'm fine, Mama."

"I can't wait to see them hand you that diploma."

She beamed, her smile washing away her scarlet face of anger.

"You're the first Landry to get a high school diploma, you know that?" she asked. Daddy hadn't told me, but she had said it a few times before in his presence when she blamed some of the things he had done on his family blood.

"Yes, Mama."

"Good. Then be proud, not nervous. Well now, we'll have to plan a little celebration for afterward, won't we?"

"No, Mama. I don't want a party."

"Sure you do. Sure," she said, nodding and talking herself into it. "I'm going to make a couple of turkeys, and I think I'll make Louisiana yam with apple stuffing. I know how you love that. Of course, we'll have some stuffed crab and some shrimp Mornay with red and green rice. I'll make some garlic grits. need some biscuits, and let's see, for desserts we should have a gingerbread, one of my coffee cakes, and maybe some caramel squares."

"Mama, you'll be working all day and night until graduation."

"So? How often will I have a graduation party for my daughter?" she said.

"But we don't have the money, do we?"

"I got a small stash your daddy didn't get his hands on," she said, winking.

"You should save it for something important, Mama."

"This is is important," she insisted. "Now hush up and go to school. Go on," she said, pushing me toward the door, "and don't you worry about how hard I work or how much I spend. I got to do what I enjoy doing and what makes me happy and proud. Especially these days," she added, scowling with thoughts of Daddy.

I shook my head. There wasn't anything I could do or say to change her mind once Mama had made up what she wanted to do. Daddy called her Cajun stubborn and said she would stare down a hurricane if she had made up her mind to do so.

"I'll come home as soon as I can to help you then," I said.

"Never mind. You do what all the girls are doing and worry about your graduation ceremony, not me," she said.

I left the house, still feeling a cloud overhead because of what had happened to me the day before; but also feeling the excitement that came with the end of school. At school no one talked about anything else. The chatter in the classroom was so loud and furious, we sounded like a yard of hens clucking. Our teachers gave up on doing anything that even vaguely resembled education.

In the afternoon they took us out to the yard on the side of the building where a portable stage had been constructed so we could rehearse the graduation ceremony. A piano had been wheeled out for Mrs. Parlange, the school secretary, to play the processional. Our principal, Mr. Pitot, was going to accompany her on the accordion, too. Together with Mr. Ternant, who was the vocal, physical education, and math teacher, and who played the fiddle, Mr. Pitot would do a few Cajun pieces to entertain the audience of grandparents, parents, brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, and friends before the speeches and the distribution of diplomas. Mr. Ternant was put in charge of the ceremony and lined us up according to height. He told us how to walk, hold our heads up high, and sit properly on the stage.

"I don't want to see anyone crossing his or her legs. And no gum chewing, hear? You all sit still, face forward, and look dignified. Every one of you is a representative of this school," he lectured. Bobby Slater made a popping sound with his mouth. Many of us smiled, but no one dared laugh. Mr. Ternant glared fiercely for a moment. Then he explained what we had to do when we were called up.

"I want you to take the diploma in this hand"—he demonstrated—"and cross over to shake like this."

He wanted us to then turn to the audience and make a small bow before returning directly to our seats.

I tried to concentrate on everything and listen carefully to all the instructions, but my mind kept wandering and returning to the incident at the lake. Yvette and Evelyn were too occupied with themselves and with their other friends to notice my distraction. I knew anyone who did notice me just thought it was my typical disinterest in things that interested them. It wasn't so. I wanted to be just as excited; I wanted to be just as young and silly and happy as they were. But every once in a while, Mr. Tate's face, just inches from mine, would flash across my eyes and I would gulp and moan softly to myself.

I was very quiet on the way home; however, Yvette and Evelyn were far more talkative than ever. A twilight gloom had pervaded my entire being, but even if I had wanted to talk, they didn't give me an opportunity to get in a word. It wasn't until we were about to part that they noticed me.

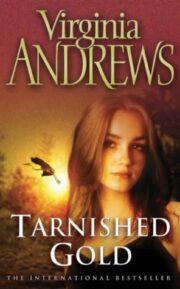

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.