"She wants to be the mother of your child very much," I said.

He smirked. "What Daphne wants, she usually gets, one way or another."

"I had the feeling she was doing this for your father as much as she was for herself and you," I told him.

He raised his eyes again and nodded. "Yes," he said. He turned away and gazed into the cypress trees. "I haven't been completely truthful with you, Gabrielle," he said in a voice so weak and troubled, I couldn't help but tremble in expectation. "I let you think of me as a fine gentleman, a man of character and position, but the truth is, I don't deserve to stand in your presence, and I certainly don't deserve your love, or anyone's love for that matter."

"Pierre . . ."

"No," he said, pulling his head back to gaze up at the sky. "I want you to understand why I care so much about my father's happiness, even more, please forgive me, than I do yours and certainly my own."

He turned back to me.

"My brother's accident was no accident. Yes, we drank too much and we shouldn't have been out in that sort of weather, and yes, he should have known all this better than me, for he was the sailor.

"But he was everything in my father's eyes, even though he was younger. He was more of a man's man, you see, an athlete, charming, handsome. He could get more with his smile and twinkling eyes than I could with all my intelligence and knowledge.

"Even Daphne, who was my fiancée at the time, was more infatuated with him than she was with me. Ours was more of a marriage of convenience, the logical couple, but with him she was romantic, even radiant; with him . . . she was the lover," he said.

"And so, when we were out there on that lake and the opportunity came to do him harm, I did and immediately regretted it. But it was too late. The damage was done. Only I had struck a blow that reached even more deeply into my parents' hearts than Jean's. My mother suffered, had heart trouble, became an invalid, and died. My father went into deep depressions, and in fact, it was only Daphne who could bring him out of them.

"She was the one who suggested we come to the bayou to hunt. It was almost as if she knew I would find you. Of course, that's ridiculous, but still . . . Anyway, when she presented the idea to me in her usual businesslike manner, and when she told me how much my father wanted it, I couldn't stop her. I couldn't care more about my promises to you. I'm sorry. I've gotten you into a much deeper mess than you ever imagined.

"I deserve your disdain, not your love," he concluded.

"That will never be," I said.

"I won't be able to come back to see you again," he warned. "And certainly I won't be able to bring our child. It wouldn't be fair to Daphne."

"I know."

"I've never known anyone as generous and loving as you, Gabrielle. I wish you could hate me. It would be easier to live with myself."

"Then you are doomed to suffer with yourself forever and ever," I told him.

He smiled. "Look at you," he said with a small laugh. "You're very pregnant," he added.

"Am I ugly now?"

"Far from it. I wish I could be there with you, holding your hand, comforting you."

"You will be," I said.

"I promise, I'll spoil our child something awful, just because whenever I look at him or her, I will see you," he vowed.

I nodded, my own tears burning under my eyelids.

"I'd better go," he said, his voice cracking.

We simply stared at each other.

"Promise you'll send word to me if you need anything, ever," he said.

"I promise."

He stepped toward me and we embraced. He kissed me and held me for a long moment.

And then he turned and walked away, into the dark path under the cypress, disappearing just as I imagined my ghost lover would. It seemed centuries ago when, on our way home from school, I had told Yvette and Evelyn about the myth.

But it wasn't a myth for me any longer.

For me, it had come true.

Epilogue

I don't remember poling home that day. One minute I was saying good-bye to Pierre forever, and the next minute I was sitting on Mama's rocker, staring out at the road, watching the sun sink below the crest of the trees and the shadows creep out of the woods and into my heart.

When Mama stepped out on the galerie, she was surprised to find me sitting there.

"I've been looking for you, honey. Where have you been?"

I smiled at her, but I didn't answer. She tilted her head for a moment, studying my face, and then her eyes filled with alarm.

"What's wrong, Gabrielle?" she asked.

I shook my head. "Nothing, Mama," I said, and held my smile.

Mama said I moved around the house like a ghost, drifting from one place to the other after that. She said I was so quiet, she thought I was walking on air. Suddenly she would turn and find me beside her.

She told me I became a little girl again, confused about time, easily hypnotized by something in Nature. She said I would sit for hours and watch honeybees gather nectar or watch birds flit from branch to branch. She swore that one day she looked out and saw me approach a blue heron. It didn't flee. She claimed I was inches from it and it had no fear. She said she had never seen anything like it.

I remembered none of this. Time drifted by as anonymously as the current in the canal. I stopped distinguishing one day from the next, and always had to be called to the dinner table. I wasn't very much help to Mama either, barely doing any of the work. If I started to do something in the kitchen, she would chase me away and tell me to rest.

It really was difficult for me to move around anyway; my stomach had gotten so big. I thought I would just explode. Mama examined me almost every day, sometimes twice, her face full of concern. Occasionally my underthings were spotted with blood and I began to have what Mama called false labor pains.

Daddy came by often during my last month. He would just wait outside, fuming. Finally, one day, while I was in the rocker, Mama stepped out to speak with him. She folded her arms under her breasts and kept her head up, her eyes cold, looking through him rather than at him.

"I'll let you know when to send for them," she said. "It's what Gabrielle wants or I wouldn't do it. You're to keep them out of the shack, hear? I don't want them settin' foot on these steps, Jack. I'm warning you. I'll have the shotgun loaded and you know I won't hesitate. After the delivery, I'll bring the baby out myself."

"Sure," Daddy said, happy she was speaking to him, even though she was really speaking at him. "Whatever you say, Catherine. How much longer is it going to be?"

"Not much," she said.

"That's good. I got some money for you," he added.

"And I told you I don't want none of that money, Jack."

"Well, maybe Gabrielle wants it," he said, nodding at me.

Mama looked at me.

"I don't need any money, Daddy," I said with a smile. He looked at Mama, puzzled.

"Just go on, Jack. God have mercy on you," she told him. He shuddered as if he had been hit with lightning and then put on his hat and stomped off. But he stopped by every day after that, sometimes twice. Mama would just come out and tell him, "Not today," and he would nod and leave.

"Too bad he couldn't have stayed so close to home before," she muttered sadly.

Almost a week later, I had a bad spell of bleeding and Mama kept me in bed all day. She didn't like the sort of pain I was having either. She fed me and washed me down and burned some banana leaves. She was praying all the time, and always trying to smile at me through a mask of worry.

"I'm all right, Mama," I told her. "I'll be just fine."

"Sure you will, honey." She squeezed my hand and read to me, and sometimes she put on the records and listened to music with me. She sat there and talked more about her childhood than ever. Her voice took on a rhythm and melody of its own, often serving as a lullaby.

At night I called to her in my dreams, and sometimes called for Pierre. I often saw him the way he was when we first met. If I stared out my window long enough, he was there in a pirogue, waving and smiling up at me, or just standing on the dock. His blue cravat was always waving in the breeze.

Sometime Mama would come upon me and ask me why I was crying. I would have to touch my face to feel the tears. "Am I crying, Mama?"

"Oh, honey, my precious little Gabrielle," she would say, and kiss me.

Almost exactly two weeks after Mama had told Daddy I would give birth, I woke in the middle of the night with the most excruciating pain I ever had. My screams brought Mama hurrying to my side. She put on the butane light and gasped. My bed was soaked with my blood.

"Oh, Gabrielle," she cried, and went to get hot towels. Daddy must have been sleeping under my window because moments later he was at the screen door. I heard him ask loudly what was going on.

"A baby's coming," Mama declared, and he was gone.

Soon after the bleeding started, my water broke. It was then and only then that Mama told me the most astounding news of all. She knelt at my side, took my hand into hers, and in a loud whisper said, "There'll be two babies, Gabrielle."

"What? Two? Are you sure, Mama?"

"I've been sure for quite a while, honey, but I didn't want to say anything for fear that scoundrel would go and sell the other one just as quickly."

"Two?" My heart was pounding so hard, I had trouble breathing. Mama put a cool cloth on my forehead.

"You don't want me to give them both, do you, honey? It's a blessing. You'll have your child. Those rich folks won't have everything after all."

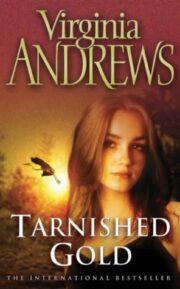

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.