I promised I would. These days I wasn't filled with too much energy and enthusiasm anyway. Even my walks were shorter, and I stopped my canoe trips through the canals. Occasionally I went along with Mama to town, but even that held no interest for me and I stopped. I spent hours at the loom or sitting on the galerie weaving palmetto baskets and hats. The mechanical work seemed to fit my empty thoughts. My- fingers moved as if they had minds of their own, and I was always surprised to discover I had finished something.

Had Daddy really driven Pierre away forever? I wondered when my mind did work. What would become of our special love? Would it wilt and crumble like leaves?

The rumble of thunder and rugs of dark clouds that were laid over the sky fit my mood. When the rains came, they seemed to wash away my memories as well as plants and flowers. Hurricane winds tore off branches and blew over tables and chairs. The shack strained and groaned. I hovered under my blankets waiting for it to end, pressing my face to the pillow, wondering how so much gloom could have come so quickly to my world of light and hope.

And then one night after a particularly bad storm, after Mama and I had to clean up our galerie and the front of the shack, Daddy came barreling in with his truck, slamming the door and whistling as if he had won the biggest bourre pot of his life. Exhausted, Mama and I were sitting at the plank table in the kitchen, neither of us with much of an appetite. She looked up at him with disgust.

"Now you come home, Jack," Mama began. "After the storm, after we done all the work, man's work?"

"This house can blow itself down to hell, for all I care," he said. "It don't matter no more."

"Is that right?" Mama began, her eyes blazing despite the film of fatigue that had settled over them. "My house don't matter no more, you say?"

"Now, just hold on, Catherine," he said, raising his hands. "Sit yourself back in that chair, hear, and behave yourself. Otherwise," he said with a wide, silly grin, "I might just not tell you what I done and what's going to be."

"I'm probably better off not hearing it if it's something you've done," Mama mumbled.

"That so? See?" he said to me. "See how she's always smart-talking me all the time, putting me down, making me look bad to my friends and neighbors?"

Mama started to laugh. "Me? No one has to work at making you look bad, Jack. You do that the best."

Daddy's smile faded. He stared at her for a moment and then he took on the most self-satisfied leer I had seen on his face. He dug into his pants pocket and came up with a fistful of money, and planted it on the center of the table. As the bills unfolded, we saw they were fifties and hundreds. It was the first time I had ever seen a hundred-dollar bill.

"What's that?" Mama asked suspiciously.

"What's it look like, woman? That there's good old U.S. currency, and that pile there is for you to do with what you please, hear?"

Mama glanced at me before looking up at Daddy again. "And where's it come from, a bourre pot filled with money folks can't afford to lose?"

"Nope. It comes from here," Daddy said, poking his right temple with his right forefinger. "It comes from being smart."

"Is that so? Well, this I gotta hear," Mama said, and sat back, her arms folded under her bosom.

Daddy went over to the cupboard, found himself some cider, and poured himself a glass first. We watched him gulp it down, his Adam's apple bobbing. He wiped his lips with the back of his hand and glared at me.

"She may know the swamp and the animals better than most around these parts," he said, nodding at me, "but she don't know nothin' when it comes to men."

"Never mind Gabrielle, Jack. We're talking about you now and what you done to get this money."

"Right. I think to myself, Jack Landry, why is it you've been the one left holding the hot potato here, huh? Why is it you got to be the one to figure out what else to do to feed another mouth, make a home, bear the brunt of insults, huh? Why is it those rich people can come in here and use us the way they want, use us like a. . a towel and then throw us away, huh? Well, they can't, is what I say!" he exclaimed, pounding the sink top with his fist.

"Most men in these here parts don't know their right from their left when it comes to going someplace other than the bayou. Once you take them out of the swamp, they're confused, stupid fools. But I ain't no swamp rat, hear? I'm Jack Landry. My great-grandpère worked the riverboats, and my mère's great-grandpère was one of the best gamblers this side of the Mississippi," he boasted. "It's true, he was hanged, but that was a mistake."

"All right, Jack. I know how wonderful your ancestors were. Get on with it," Mama demanded.

"Yeah. You know. You know everything, don'tcha, Catherine Landry? Anyways, I upped and took myself to New Orleans."

"What?" I said with a gasp.

"That's right," he said, his eyes blazing.

"What were you doing in New Orleans, Jack?" Mama asked.

"I found out where those Dumas men live and I paid 'em a little visit. Turns out the old man is not really unhappy with what I come to tell him either," Daddy said, nodding.

Mama stared, astounded. She looked at me and then she leaned forward.

"What did you tell him, Jack?"

"I told him about Gabrielle here and the condition his son put her into," he said, standing proud. "That's what I told him, and I didn't spare no words, neither. I told him about the shack and the way he done seduced my little girl."

"He did not!" I cried.

"Hush a moment," Mama said, her eyes brighter, her face flushed. "Go on, Jack. What else did you tell him?"

"I told him I was about to bring Gabrielle into New Orleans and take her to the newspaper people if I had to," he said, nodding and smiling. "I would let the whole city know what his fine, upstanding, well-to-do businessman son done to a poor, innocent girl in the bayou."

"Where was Pierre?" I asked, my heart pounding.

"Hiding himself someplace, I bet," Daddy said. "He didn't show his face the whole time I was there. They got a palace, not a house, Catherine. You can't even imagine the rich things in the house and the size of the rooms, and there's a tennis court and a swimming pool and—"

"I don't care about any of that, Jack. Just tell us what you told Monsieur Dumas."

"Well, I expected to get the money I needed to look after Gabrielle here. You ain't gonna find yourself a good husband now, Gabrielle," he said, turning to me and shaking his head. "A woman with a child and no marriage ain't got a chance and certainly ain't got the pickin's. Why, I couldn't even get you Nicolas Paxton now, and it's your own doin'."

"Never mind all that, Jack. You haven't told us anything we don't know."

"Right." He straightened up. "Well, Monsieur Dumas, he says his son already told him about what he had done. He knew the details, and what's more, he said his son's wife knew the details, so I couldn't threaten him none."

"His wife?" I gasped.

"That's right. That's what he says, and full of arrogance, too. I was about to protest and start ragin' at him when he puts up his hand, looks away for a moment, and then says he's willing . . . no, he wants to buy the child."

"No!" I cried.

"Not again, Jack?" Mama said. "You didn't go and make a bargain with the devil again?"

"This is different, Catherine," Daddy protested. "We got no way to hide Gabrielle's condition. We can't keep the community from knowing she's a fallen woman. I got to look after the future. These people are so rich, they make the Tates look like paupers. You see that pile of money there?" he said, pointing to the table. "Well, that's just payment for me to think on it. I'm going to get us enough to take care of us forever. We don't have to worry about Gabrielle finding herself a good man, see? And you don't have to go running off at everyone's beck and call to tend to their insect bites and coughs."

Mama was silent a moment. The tears were streaming down my cheeks. Where was Pierre? How could he have permitted his father to make such an offer? Mama rose to her full height, which wasn't much, but with her eyes wide, she looked taller, and Daddy stepped back, shaking his head.

"You gotta admit I done good, Catherine. You gotta admit that."

"You done good? You done good? How, Jack? By running off to sell your daughter's child? You think children are just like a bag of oysters? It's part of her, which makes the child part of us, too. It's our flesh and blood."

"And it's our burden," Daddy said, his determination firmer than I had ever seen. He didn't flinch or retreat from Mama's anger as he usually did. "I know I done right." His courage mounted, his chest pumped. "I'm the man here, see? I make the decisions. You might be the best traiteur in these parts, Catherine, but you're still my wife and that's still my daughter, and what I decide is . . . is what will be when it comes to this family, hear?"

"Go to hell, Jack Landry," Mama said. Daddy's face turned so red, I thought the top of his head would explode. He looked at me. I was holding my breath, my eyes so wide, they hurt. It only added to his embarrassment. "Take your bargain back to the devil," Mama hissed.

Daddy didn't retreat.

Mama started toward him, and suddenly he swung his open right palm and caught her on the side of the face. The blow sent her flying against the table. I screamed. Daddy stood there, surprised at what he had done himself. He started to stutter and stammer an apology as Mama shook the dizziness out of her head and stood up to him again. This time she pointed her finger at the door. When she spoke, it was barely above a whisper, her voice cold and throaty.

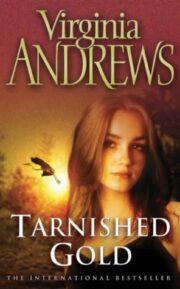

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.