"You went out after your daddy and me left last night, didn't you, Gabrielle?"

"Yes, Mama."

"Where did you go?"

"Just for a walk and then a short ride in the pirogue," I said. I put some jam on my biscuit.

"You met that man someplace, didn't you, Gabrielle?" she asked directly. My heart stopped and then fluttered. "You can't lie to me, Gabrielle. It's written in your face."

"Oui, Mama," I confessed. She was right: Keeping the truth from Mama was like trying to hold back a twister.

"Oh, honey," she moaned. "After what you've been through, you've suffered, to go and start with another married man."

"We love each other, Mama. It's different and it's not like anything I've ever felt before," I protested.

"How would you know?" she asked with a stern face. "You've never really had a boyfriend."

"It can't be this good with anyone else."

"Of course it can. You're just feeling your first real excitement, and with a very sophisticated, rich city man who probably has a half dozen young mistresses," she declared.

Such an idea had never occurred to me.

"No, Mama, he said . . ."

"He'd say anything to get you where he wants you, Gabrielle." She leaned toward me so I couldn't look away from those all-knowing eyes. "And he would make any promise to get what he wants. If you believe him, it's because you want to, first, and second, because he's done it so many times before, he's good at it," she concluded.

I stared, thinking. Then I shook my head. "He can't be that way; he can't," I insisted, as much to myself as to her.

"Why not, Gabrielle?"

"I feel him," I said, putting my hand over my heart, "deeply in here, My feelings have never betrayed me before," I insisted, building my own courage. "Since I was a little girl, I have known what is true and what is not. My animals . . ."

"Animals are so much simpler than people, Gabrielle. They are not conniving and deceitful."

"Tell that to my spiders," I shot back. Mama's eyes softened for a moment with a little amusement, but then she grew worried again.

"All right, what of your spider who sets up such a seemingly harmless world around him, so innocent looking, the fly always steps into it and realizes it too late?

"A rich, sophisticated man like Monsieur Dumas has the power to weave a very inviting world around him. He will catch you in it, and when you realize it, it will be too late."

"Pierre is no more conniving than I am, Mama. You don't know him yet."

"And you do? Already?"

"Our feelings for each other have opened our hearts and minds to each other. When you love each other deeply, truly, it takes only minutes to know everything there is to know. He has told me of his great unhappiness and I see how much he suffers, even though he is a wealthy man."

"And what of his wife, then?" she asked.

"They lead separate lives right now. She has been unable to give him a child and she is more involved with her society friends than with him," I explained.

"But where will all this take you, Gabrielle?" she asked with despair.

"I don't know," I admitted.

"And for the moment, you don't care because you're blinded by your feelings and your excitement. Don't you think I know how desperate you are for a real love, how much you need someone who will love you truly, especially after your horrid experience? You're jumping on the first opportunity, only it's not an opportunity, Gabrielle. It's like a false dawn. You're going to plummet into a deeper darkness."

She sat back firmly, her words lying heavy in the air between us.

"I want you to tell this man first chance you get that you won't ever see him again, hear? If you don't, I will, Gabrielle, even if it means marching down that road all the way to New Orleans and knocking on his front door," she threatened.

"Oh Mama, please . . ."

"If I stood by and watched you drown, I'd be wrong, wouldn't I? Well, I ain't gonna stand by and watch this, neither," she vowed.

We heard the floorboards above us groan.

"It's best your daddy don't know nothing about this, Gabrielle, hear?"

"Yes, Mama." I looked down.

"I'm sorry, honey, but I know what's best for you."

I shot an angry glance at her. Why did she always know what was best for me? She wasn't me. What did she think it was like having a traiteur for a mother, thinking all these years that my every thought, my every feeling, was as naked as a newly born doe before her eyes? Besides, I thought, when it came to love, Mama wasn't infallible. Look at the mistake she had made, the marriage she had. Defiant, I rose from the table and left the room.

"Gabrielle!"

The front door slammed shut behind me as I jogged down the galerie steps and around back, heading toward the canal. I remained away from home most of the day, wandering through my paths, weaving along the water, sitting on a big rock and watching the birds and the fish. I spent most of the time arguing with myself.

The sensible side of me took Mama's side, of course, claiming she was only looking out for my happiness and trying to protect me from sadness and disappointment. That side of me warned against living for the moment. It ridiculed the pledge Pierre and I had made to each other. What sort of a pledge was it anyway, a pledge to ignore everything and anything but our own pleasure? Living for the moment was shortsighted. What would happen when that day of reckoning came?

The other side of me, the wild and free side that found its strength in Nature, that side of me which was never comfortable confined by clothes and houses and man-made rules, refused to listen. Look at the birds. They don't sit worrying about the winter; they enjoy the spring and the summer and feel the warm breeze around them when they glide through the air, free . . . happy.

And what of these people who have been sensible and who have married the so-called right person? What of these people who have never been naked under the sun and the stars, who have listened first to their minds and then their hearts? Trapped in their wise and reasonable decisions, they wither away wondering what it might have been like if they had followed their feelings instead of their thoughts.

But your mama followed her feelings instead of her thoughts, my sensible side retorted. That thought shut me up for a while. I sat there, brooding. My sensible side continued. She's only trying to give you the benefit of her wisdom, a wisdom unfortunately gained through pain and suffering. Can't you take her gift gracefully and stop being a stubborn, selfish little girl?

I swallowed back my tears and took a deep breath.

Still defiant, or tying to be, I turned my face to the wind and screamed.

"I love Pierre! I will always love him. I won't give him up. I won't!"

My words were swept away. They changed nothing. It didn't take very much effort to scream them; I could scream them again. What took great effort was to shut them up in my heart, to lock the door on that secret place within me where Pierre's face resided and his words resounded.

As I started walking back home, I wondered if every birth, whether it be the birth of a tadpole or the birth of a spider or the birth of a human being, was another beat in the heart of the universe. Maybe my birth was an irregular beat. I was simply out of sync with the rhythms of this world, and I would not ever find a place in it. I would never find happiness and a love that could be. I was destined to be an outcast. Maybe that was why I was so drawn to simple, natural things and felt safer in the swamp than I did in society.

Mama looked up from the clothes she was washing in the rain barrel when I appeared. She wasn't angry; she was very sad for me. She stopped working and waited as I drew closer.

"I'll tell him I won't see him anymore, Mama," I said. "It's the best thing, Gabrielle."

"The best thing shouldn't be so hard to do," I replied angrily, and went into the shack.

Almost a week went by before I heard from Pierre again. During that time I sat by the window in my room and looked out over the canals toward New Orleans and wondered what he was thinking, what he was doing. In my mind I wrote and rewrote my letter to him until I found the words, and then I sat at the kitchen table late one night after Daddy and Mama had gone to bed and put the words on paper.

Dear Pierre,

Some women think giving birth is the hardest and most painful experience of their lives. Afterward, of course, there is a wonderful reward. But I think the birth of these words on this paper is the hardest and most painful thing for me. There is no wonderful reward either.

I can't see you anymore. I love you; I won't lie and deny that, but our love, as beautiful as it seems, is a double-edged sword that will turn on us someday, perhaps sooner than we expect. We will hurt each other deeply, perhaps too deeply to recover, and maybe, just maybe, we will even grow to hate each other for what we have done to each other, or worse, hate ourselves for it.

I don't pretend to be a very wise person. Nor have I ever assumed I have inherited my mother's powers, but I don't think it takes a very wise person or a clairvoyant to see our future. We are like a stream, rushing, gleaming, sparkling, and full, that suddenly turns a corner and drops over a ledge to pound itself on the rocks below and then stagnate.

I can't let this happen to you or to me. Please try to understand. I want you to be happy. I hope your problems will end and you will have a good and fruitful life where you are, where you belong.

Sell this shack and go home, Pierre. Do it for both our sakes.

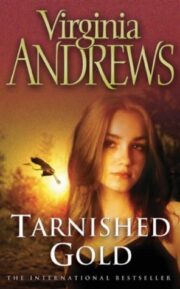

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.