"So," Mama said when I brought a pile of our goods to the stand, "you were speaking to that nice young man, I see."

"Yes, Mama. He says he doesn't really like to hunt but goes along for his father's sake."

Mama nodded. "I think we have a lot to learn from your animals and birds, Gabrielle. After the babies are nurtured, their parents let them go off and be their own selves."

"Oui, Mama," I said. When I looked up at her, her eyes were wider and bright with curiosity, but she wasn't looking at me. She was gazing over my shoulder toward the dock. I turned and saw Pierre strolling back while Papa and the other men were casting off in the canoes.

"I'll go check on my roux," Mama said, and headed for the house.

"Monsieur," I said, "aren't you going on your swamp hunt?"

"Don't know why," he said, "but I have a little headache and decided to rest instead. I hope you don't mind."

"Oh no, monsieur. I'll speak to my mother about your headache. She's a traiteur, you know."

"Traiteur?"

I explained what she was and what she did.

"Remarkable," he said. "Perhaps I should bring her back to New Orleans with me and set her up in business. I know a great many wealthy people who would seek her assistance."

"My mother would never leave the bayou, monsieur," I said with a deadly serious expression. He laughed. "Nor would I," I added, and his smile faded.

"I don't mean to make fun of you. I'm just amused by your self-assurance. Most young women I know are quite insecure about their beliefs. First they want to check to see what's in style or what their husbands believe before they offer an opinion, if they ever do. So," he said, "you've been to New Orleans?"

"No, monsieur."

"Then how do you know you wouldn't want to live there?"

"I know I could never leave the swamp, monsieur. I could never trade cypress and Spanish moss, the willow trees and my canals, for streets of concrete and buildings of brick and stone."

"You think the swamp is beautiful?" he asked with a smile of incredulity.

"Oui, monsieur. You do not?"

"Well, I must confess I haven't seen much of it, nor have I enjoyed the hunting trips. Perhaps," he added, "if you have the time, you would give me a little tour. Show me why you think it's so nice here."

"But your headache, monsieur," I reminded him.

"It seems to have eased quite a bit. I think I was just nervous about going hunting. I would pay you for your tour, of course," he added.

"I wouldn't charge you, monsieur. What is it you would like me to show you?"

"Show me what you think is beautiful, what gives you this rich look of happiness and fills your face with a glow I know most of the fancy women in New Orleans would die to have."

I felt my cheeks turn crimson. "Please, monsieur, don't tease me."

"I assure you," he said, standing firm, his shoulders back, "I mean every word I say. How about the tour?"

I hesitated.

"It doesn't have to be long. I don't mean to take you away from your work."

"Let me tell my mother," I said, "and then we'll go for a walk along the bank of the canal."

"Merci."

I hurried to the shack to tell Mama what the young man wanted. She thought for a moment.

"Young men from the city often have low opinions of the girls from the bayou, Gabrielle. You understand?"

"Oui, Mama, but I don't think this is true about this young man."

"Be careful and don't be long," she warned. "I haven't looked at him long enough to get a reading."

"I'll be safe, Mama," I assured her.

Pierre was standing with his hands behind his back, gazing over the water.

"I just saw a rather large bird disappear just behind those treetops," he said, pointing.

"It's a marsh hawk, monsieur. If you look more closely, you will see she has a nest there."

"Oh?" He stared. "Oui. I do see it now," he added excitedly.

"The swamp is like a book of philosophy, monsieur. You have to read it, think about it, stare at it, and let it sink in before you realize all that's there."

His eyebrows rose. "You read philosophy?"

"A little, but not as much as I did when I was in school."

"How long ago was that?"

"Three years."

"You're an intriguing woman, Gabrielle Landry," he said.

Once again I felt the heat rise up my neck and into my face. "This way, monsieur," I said, pointing to the path through the tall grass. He followed beside me. "What do you do, monsieur?"

"I work for my father in our real estate development business. Nothing terribly exciting. We buy and sell property, lease buildings, develop projects. Soon there will be a need for low-income housing, and we want to be ready for it," he added.

"There's some very low-income housing," I said, pointing to the grass dome at the edge of the shore. A nutria poked out its head, spotted us, and recoiled. Pierre laughed. I reached out and touched his hand to indicate we should stop.

"What?"

"Be very still a moment, monsieur," I said, "and keep your eyes focused on that log floating against the rock there. Do you see?"

"Yes, but what's so extraordinary about a log that . . . Mon Dieu," he remarked when the log became the baby alligator, its head rising out of the water. It gazed at us and then pushed off to follow the current. "I would have stepped on it."

I laughed just as a flock of geese came around the bend and swooped over the water before turning gracefully to glide over the tops of the cypress trees.

"My father would have blasted them," Pierre commented. We walked a bit farther.

"The swamp has something for every mood," I explained. "Here in the open with the sun reflecting off the water, the lily pads and cattails are thick and rich, but there, just behind the bend, you see the Spanish moss and the dark shadows. I like to pretend they are mysterious places. The crooked and gnarled trees become my fantasy creatures."

"I can see why you enjoyed growing up here," Pierre said. "But these canals are like a maze."

"They are a maze. There are places deep inside where the moss hangs so low, you would miss the entrance to a lake or to another canal. In there you rarely find anything to remind you of the world out here."

"But the mosquitoes and the bugs and the snakes . . ."

"Mama has a lotion that keeps the bugs away, and yes, there are dangers,but, monsieur, surely there are dangers in your world, too."

"And how."

He laughed.

"I have a small pirogue down here, monsieur, just big enough for two people. Do you want to see a little more?"

"Very much, merci."

I pulled my canoe out from the bushes and Pierre got in. "You want me to do the poling?"

"No, monsieur," I said. "You are the tourist."

He laughed and watched me push off and then pole into the current.

"I can see you know what you're doing."

"I've done it so long, monsieur, I don't think about it. But surely you go sailing, n'est-ce pas? You have Lake Pontchartrain. I saw it when I was just a little girl and it looked as big as the ocean."

He turned away and gazed into the water without replying for a moment. I saw his happy, contented expression evaporate and quickly be replaced with a look of deep melancholy.

"I did do some sailing," he finally said, "but my brother was recently in a terrible sailing accident."

"Oh, I'm sorry, monsieur."

"The mast struck him in the temple during a storm and he went into a coma for a long time. He was quite an athletic man and now he's . . . like a vegetable."

"How sad, monsieur."

"Yes. I haven't gone sailing since. My father was devastated by it all, of course. That's why I do whatever I can to please him. But my brother was more of the hunter and the fisherman. Now that my brother is incapacitated, my father is trying to get me to become more like him, but I'm failing miserably, I'm afraid." He smiled. "Sorry to lay the heavy weight of my personal troubles on your graceful, small shoulders."

"It's all right, monsieur. Quick," I said, pointing to the right to help break him from his deeply melancholy mood, "look at the giant turtle."

"Where?" He stared and stared and then finally smiled. "How do you see these animals like that?"

"You learn to spot the changes in the water, the shades of color, every movement."

"I admire you. Despite this backwoods world in which you live, you do appear to be very content."

I poled alongside a sandbar with its sun-dried top and turned toward a canopy of cypress that was so thick over the water, it blocked out the sun. I showed Pierre a bed of honeysuckle and pointed out two white-tailed deer grazing near the water. We saw flocks of rice birds, and a pair of herons, more alligators and turtles. In my secret places, ducks floated alongside geese, the moss was thicker, the flowers plush.

"Does your father take hunters here?" Pierre asked. "No, monsieur." I smiled. "My father does not know these places, and I won't be telling him about them either." Pierre's laughter rolled over the water and a pair of scarlet cardinals shot out of the bushes and over our heads. On the far shore, a grosbeaked heron strutted proudly, taking only a second to look our way.

"It is very beautiful here, mademoiselle. I can understand your reluctance to live anywhere else. Actually, I envy you for the peace and contentment. I am a rich man; I live in a big house filled with beautiful, expensive things, but somehow, I think you are happier living in your swamp, in what you call your toothpick-legged shack."

"Mama often says it's not what you have, it's what has you," I told him, and he smiled, those green eyes brightening.

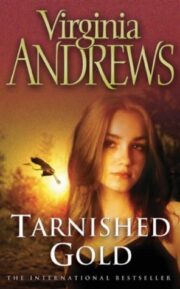

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.