If we did, I would tell you that when you were born, I thought it was glorious and I was filled with such love for you, I feared my heart would burst. I would tell you I spent night after night crying when I thought about you. I would tell you I was sorry.

Of course, you might hate your father and resent your stepmother, so I have to think hard before I tell you these things. It might be that for your sake I never do, because your happiness is far more important to me than my own.

I just want you to know I love you, and even though I didn't want it to happen, you became a part of me and always will be.

Love,

Your mother Gabrielle

I kissed the paper and folded it tightly. Then I stuck it in my top drawer with my most precious momentos. It felt good to write it even though I knew Paul would never read it.

The moon poked its face between two clouds and sent a shaft of yellow light over the swamp. It looked magical for a moment, and I could swear I heard the cry of a baby. It echoed over the water and drifted into the darkness. I curled up in my bed and pretended I had baby Paul in my arms, his tiny face pressed up against my breast, my heartbeat giving him comfort.

And I fell asleep, dreaming of a better tomorrow.

9

A Tormented Spy

On warm nights when the moon peered through clouds no thicker than dreams, I would sit on Daddy's dock with my bare feet just above the water that lapped gently against the dark wooden posts, and I would listen for the cry of a raccoon. To me, a raccoon sounded like a human baby crying. I would think about Paul and how much and how quickly he had grown these past three years. Occasionally I would catch sight of him either in town with the Tates or at church whenever they would bring him along. I hoped God would forgive me, for I went to church more to catch a glimpse of my baby than I went for the service. However, most of the time the Tates would leave Paul at home with the nanny on Sundays. I learned Gladys didn't like being bothered with a baby when she was in public. I'd never complain, I thought.

The small patch of blond hair with which Paul had been born had become a full head of chatlin hair, the blond strands just a little thicker and brighter than the brown. His eyes were the soft blue shade of the sky in the morning when the sun was just climbing from the east and the sable darkness was sliding down the horizon on the west.

Whenever Gladys Tate saw that I had caught Paul's eye, whether it be in town or at church, she would immediately toss him from one side to the other so her body would block me from Paul's sight. It was difficult for me to get close to him. Once, only once, when they were leaving the church and I had deliberately lingered behind at the doorway, I was no more than a few inches from him. I saw how graceful his hands were and how creamy pink was his complexion. I heard his sweet peal of laughter and when he turned his head my way, I saw him smile, his eyes brightening as if there were tiny blue bulbs behind them. I could see he was a happy baby, plump and content. I was glad about that, but I was also saddened by the thought that he might really be better off with the rich Tates, who could give him so much, and not with me, who could give him so little.

For this particular day at church, he was dressed in a little sailor's outfit and his shoes were spotless, bone white. There was no question he had everything he needed and would ever want. He looked healthy, alert, and loved. I was no more than a passing shadow in his presence, nothing more than just another strange face; yet his bright round eyes lingered long enough for Gladys to realize it. When she turned and saw it was I standing there, her cheeks turned crimson with anger. She hoisted her shoulders and quickened her step, practically flying past Octavious, who was surprised for the moment. She muttered something to him and he spun around to look at me, too. He grimaced as if he had just experienced a gas spasm in his stomach and then hurried to catch up to Gladys, who had already dropped Paul into the arms of their nanny as if he were nothing more than a rattlesnake watermelon. The baby was quickly shoved into the car, and a few moments later, they were off, the dust clouds rising behind their luxurious automobile.

I couldn't help wanting to see Paul as often as possible, to see the changes and the development in him. I cherished a newspaper photo of the Tates that had appeared in the local paper's society pages because Paul was just visible between Gladys and Octavious. I kept the clipping close to my bedside so I could look at it under the light of a butane lantern every night. I had opened and folded the clipping so many times, the words were practically illegible.

Mama knew the pain I was in, the way I tossed and turned at night regretting the agreement I had made. She could see the agony in my eyes every time someone appeared with a baby in her arms, whether it be one of our neighbors or a tourist stopping to buy something from our roadside stand. I volunteered to watch anyone's baby. I needed to be around the diapers, the pablum, the rattles. I needed to hear the giggles and the cooing and even needed to hear the cry for food or attention.

"I know why you upped and volunteered to watch Clara Sam's baby this afternoon, Gabrielle," she would say whenever I offered. "You're just tormenting yourself, child."

"I can't help it, Mama. I'd rather have a few moments of pleasure, even though I know when Clara Sam comes to take her baby home, I will feel my own emptiness that much more."

"That you will," Mama predicted, and threw an angry glance in Daddy's direction.

Most of the time Daddy pretended none of it had happened. Whenever Mama made reference to the money he had gotten from the Tates and then squandered, Daddy would either act deaf or say she didn't know what she was jabbering about. We knew that even though he had been thrown off Octavious Tate's property and threatened with being arrested and put in jail, he had tried on at least two subsequent occasions to get more money out of him; but always to no avail.

"The man has no conscience," Daddy would wail. "Rich men like him who make their fortunes on the backs of honest laboring men never have a conscience."

"What honest laboring man might that be, Jack?" Mama snapped. "Surely you're not referring to yourself."

"And surely I am! Just 'cause I've been through some hard times, it don't mean I don't put in a hard day's work, woman. Look at me now. I put food on the table, don't I?" he protested.

Mama just shook her head and returned to weaving her palmetto basket. She couldn't argue. Daddy had been employed at his present job longer than he had at anything else I could remember. He was working as a guide for Jed Atkins, who ran a swamp touring company and who provided boats, tackle, and guns for tourists and for rich city men who came to the bayou to hunt ducks or white-tail deer.

Jed was Daddy's favorite sort of boss. He drank a great deal of homemade whiskey himself, smoked, and cursed every fourth word. He lived alone in the rear of his gun, tackle, and boat shop, which was a wooden building so rotted, it looked like it would collapse the moment the vermin and insects that had made it their home decided to leave.

Despite his drinking, gambling, and fighting, Daddy had developed a good reputation as a swamp guide. It seemed he fit the bill because he looked and talked the way rich Creoles from New Orleans expected a Cajun swamp guide would look and talk. For an extra dollar, he would pose for their pictures: his hair wild, his beard straggly, his skin tan and leathery.

The truth was, Daddy always found them ducks or got them to get off some good shots at deer. Daddy knew his swamp; he was as much a part of it as a nutria or gator, but I hated the work he was doing because the men he guided were men who killed for sport and not for food or clothing. Some of them left the animal carcasses where they shot them because they weren't big enough or impressive enough trophies.

But between what Daddy made, or what he would bring to Mama before he gambled or drank away, and what Mama and I would make weaving baskets and blankets and selling jams and gumbo, we were doing better than ever. Daddy got himself a later-model truck, and Mama bought a new set of dishes from the Tin Man who came by in his van. On my nineteenth birthday, Mama had Daddy buy me a watch. It was silver with Roman numerals. It had a thin, black band. Daddy thought it was a waste of money.

"She can tell the time better than any watch just by looking at the sun," he explained. "No one reads the signs in Nature better than Gabrielle."

"A young woman nowadays should have a nice watch," Mama insisted.

"I wouldn't mind it if she went places where some young man could consider her for to be his wife," Daddy said. "Actually," he added after mulling it over a moment and chewing on his lip, "I'm glad she has a watch. She can hear time tickin'. 'Fore you know it, she'll be twenty and unmarried. Then who'll come for her? Huh, Catherine? Not one of your well-to-do respectable town boys, no. And if one comes along and learns she ain't a virgin . . . she'll be lucky she gets one of my swamp rats."

"You stop that talk, hear, Jack Landry?" Mama said, snapping her forefinger at him, the way someone would snap a whip. "I'll put a curse on any man who talks poorly about Gabrielle, hear? Any man," she emphasized, her eyes blazing.

"Well, she don't go to no dances; she don't talk to anyone at church, she don't go anywhere 'less you go, and all she does is follow you around on your traiteur missions. Most men round here think she's strange because of all the time she spends in the swamp. I know," he said, poking his own long right forefinger into his own chest so hard, I had to wince with the imagined pain. "I hear 'bout it all the time at the boathouse.

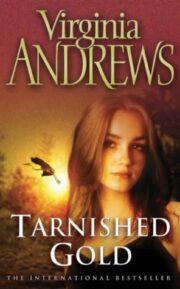

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.