Evelyn was going to marry Claude LeJeune, who had his own shrimp boat, and Yvette was going to Shreveport to live with her aunt and uncle on their sugar plantation. Everyone understood she would eventually marry the foreman, Philippe Jourdain, with whom she had carried on a letter correspondence all year. They had really seen each other only twice and he was nearly fifteen years older, but Yvette was quite convinced that this should be her destiny. Philippe was a Cajun, and Yvette, like most of us, would marry no one else. We were descendants of the French Arcadians who had migrated to Louisiana and we cherished our heritage.

It was 1944. The Second World War still raged and young, eligible Cajun men were still scarce, even though most farmers and fishermen had exemptions. Evelyn and Yvette were always chiding me for not paying attention to Nicolas Paxton, who was going to inherit his father's department store someday. He was overweight and had flat feet, so he would never be drafted.

"He's always been very fond of you," Yvette said, "and he's sure to ask you to marry him if you gave him the time of day. You won't be poor, that's for sure, n'est-ce pas?" she said with a wink.

"I don't know which I would hate most," I replied. "Waking up in the morning and seeing Nicolas beside me or being shut up in that department store all day saying, 'Can I help you, monsieur? Can I help you, madame?"'

"Well, you've turned away every other possible beau. What are you going to do after graduation, Gabrielle, weave split-oak baskets and palmetto hats with your mother and sell gumbo to tourists forever and ever?" Evelyn asked disdainfully.

"I don't know. Maybe," I said, smiling, which only infuriated my sole two friends more.

It was a very warm late spring day. The sky was nearly cloudless, the blue the color of faded dungarees. Gray squirrels with springs in their little legs leapt from one branch to another, and during the rare moments when we were all quiet, I could hear woodpeckers drumming on the oak and pecan trees. It was too glorious a day to get upset over anything anyone said to me.

"But don't you want to get married and have children and a home of your own?" Yvette demanded as if it were an affront to them that I wasn't engaged or promised.

"Oui. I imagine I do."

"You imagine? You don't know?" Her lips moved to twist into a grotesque mockery. "She imagines."

"I suppose I do," I said, committing myself as much as I could. My friends, as well as all the other students at school who knew me, thought I was born a bit strange because my mother was a spiritual healer. It was true that things that annoyed them didn't bother me. They were always fuming and cursing over something some boy said or some girl did. Truly, most of the time I didn't even notice. I knew they had nicknamed me La Fille au Nature!, the Nature Girl, and many exaggerated stories about me, telling each other that I slept with alligators, rode on the backs of snapping turtles, and never was bitten by mosquitoes. I was rarely bitten, that was true, but it was because of the lotion Mama concocted and not because of some magic.

When I was a little girl, boys tried to frighten me by putting snakes in my desk. The girls around me would scream and back away, while I calmly picked up the snake and set it free outside the building. Even my teachers refused to touch them. Most snakes were curious and gentle, and even the poisonous ones weren't nasty to you if you let them be. To me, that seemed to be the simplest rule to go by: Live and let live. I didn't try to talk Yvette out of marrying a man so much older, for example. If that was what she wanted, I was happy for her. But neither she nor Evelyn could treat me the same way. Because I didn't think like they did and do the things they wanted to do, I was foolish or stubborn, even stupid.

Except for the time Nicolas Paxton invited me to a fais do do at the town dance hall, I had never been invited to a formal party. Other boys had asked me for dates, but I had always said no. I had no interest in being with them, not even any curiosity about it. I looked at them, listened to them, and immediately understood that I would not enjoy being with them. I was always polite in refusing. A few persisted, demanding to know why I turned them down. I told them. "I don't think I would enjoy myself. Thank you."

The truth was a shoe that almost never fit gracefully on a twisted foot. It only made them angrier and soon they were spreading stories about me, the worst being that I made love with animals in the swamp and didn't care to be around men. More than once Daddy got into a fight at one of the zydeco bars because someone passed a remark about me. He usually won the fight, but still came home angry and ranted and raved about the shack, bawling out Mama for putting "highfalutin" ideas in my head about love and romance.

"And you," he would shout, pointing his longer forefinger at me, the nail black with grime, "instead of playing with birds and turtles, you should be flittin' your eyes and turnin' your shoulders at some rich buck. That pretty face and body you've been blessed with is the cheese for the trap!"

The very idea of being flirtatious and conniving with a man made my stomach bubble. Why let someone believe you wanted something you really didn't? It wasn't fair to him and it certainly wasn't fair to myself.

However, even though I never told my two girlfriends or even Mama for that matter, I did think about love and romance; and if believing something magical had to happen between me and a man was "highfalutin," then Daddy was right. I didn't want people to think I was a snob, but if that was the price I had to pay to believe in what I believed, then I would pay it.

Everything in Nature seemed perfect to me. The creatures that mated and raised and protected their offspring together were designed to be together. Something important fit. Surely it had to be the same way for human beings, too, I thought.

"I can't do that, Daddy," I wailed.

"I can't do that, Daddy," he mimicked. Liquor loosened his tongue. Whenever he returned from the zydeco bars, which were nothing more than shacks near the river, he was usually meaner than a trapped raccoon. I had never been in a zydeco bar, but I knew the word meant vegetables, all mixed up. Often I heard the African-Cajun music on the radio, but I knew that more took place in those places than just listening to music.

Of course, I burst into tears when Daddy ridiculed me, and that set Mama on him. The fury would be in her eyes. Daddy would put his arms up as if he expected lightning to come from those dazzling black pupils. It sobered him quickly and he either fled upstairs or out to his fishing shack in the swamp.

My biggest problem was understanding why Mama and Daddy married and had me. They were beautiful people. Daddy, especially when he cleaned up and dressed, was about as striking a man as I had ever seen. His complexion was always caramel because of his time in the sun, and that darkness brought out the splendor of his vibrant emerald eyes. Except for when he was swimming in beer or whiskey, he stood tall and flu in as an oak tree. His shoulders looked strong enough to hold a house, and there were stories about him lifting the back end of an automobile to get it out of a rut.

Mama wasn't tall, but she had presence. Usually she wore her hair pinned up, but when she let it flow freely around her shoulders, she looked like a cherub. Her hair was the color of hay and she had a light complexion. Her eyes weren't unusually big, but when she fixed them angrily on Daddy, they seemed to grow wider and darker like two beacons drawing closer and closer. Daddy couldn't look at her directly when she interrogated him about things he had done with our money. He would put up his hand and plead, "Don't look at me that way, Catherine." It was as if her eyes burned through the armor of his lies and seared his heart. He always confessed and promised to repent. In the end she took mercy on him and let him slip away on his magic carpet of promises for better tomorrows.

As I grew older, Mama and Daddy grew further apart. Their bickering became more frequent and more bitter, their animosity sharp and needling. It hurt to see them so angry at each other. As a child, I recalled them sitting together on the galerie in the evening, Daddy holding her in his arms and Mama humming some Cajun melody. I remember how Mama's eyes clung worshipfully to him.

Our world seemed perfect then. Daddy had built us the house and was doing well with his oyster fishing and frequent small carpentry jobs. He wasn't a guide for rich Creole hunters yet, so we didn't argue about the slaughter of beautiful animals. We always appeared to have more than we needed during those earlier days. People would give us gifts in repayment for the healing Mama performed or the rituals she conducted, too.

I know Daddy believed he was blessed and protected because of Mama's powers. He once told me his luck changed after he married her. But he came to believe that that same spiritual protection would carry over when he indulged in backroom gambling, and that, according to Mama, was the start of his downfall.

What I wondered now was, how could two people who had fallen so deeply in love fall so quickly out of it? I didn't want to ask Mama because I knew it would make her sad, but I couldn't keep the question locked up forever. After a particularly bad time when Daddy came home so drunk he fell off the galerie and cracked his head on a rock, I sat with Mama while she fumed and asked her.

"If you have the power to see through the darkness for others, why couldn't you have seen for yourself, Mama?"

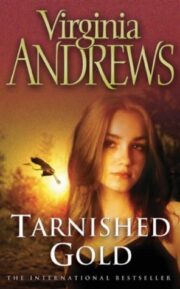

"Tarnished Gold" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Tarnished Gold". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Tarnished Gold" друзьям в соцсетях.