She shakes her head.

SOPHIE: Not that, your career. You had everything. Most people would kill to be in your position. The money, the fame … And you turn your back on it. I don’t understand. Do you not have any clue how incredibly lucky you were?

I take a moment to process everything she’s said. I guess from the outside, my life seems storybook to some (at least those who think hitting your peak at ten is enviable). But Sophie should know better — she’s seen the hours I’ve had to work, how invasive the press can be. And, yes, I’ve been lucky. Incredibly lucky. But that and some hard work were all that I had. Not talent. Not passion.

And suddenly it dawns on me. Sophie has had success at CPA even though she doesn’t think she has. She’s been part of every production. Granted, most of the time it was as a background player, but she still got in. But she was never happy unless she was a star. I think of Emme happily strumming in the background.

ME: Sophie, did I ever tell you about the background artist I became friends with on the Kids set?

She stares at me blankly.

ME: He was this really great guy named Bill. He came in every day, sat with the other extras, and never complained. Extras hardly get paid, they don’t get any glamour, not to mention lines. They work long hours for no glory. But Bill always had a smile on his face.

I can tell Sophie is getting bored. But I don’t care; I think this could help her.

ME: So one day, I went up to him because I wanted to know his story. I found out that he works at a grocery store to help pay the bills, but he’d always loved movies as a kid. So his dream was to spend time on a movie set. He didn’t look at the work as being beneath him; he was happy just to be there.

SOPHIE: So what, he turned out to be some famous actor? Or are you saying that I need to think that being stuck in a chorus isn’t beneath me?

ME: I’m just saying that if all you want out of a career is money and fame, you’re never going to be happy. Not once did you ever show any interest in the ins and outs of my job — you were only interested in the spotlight. You’re only happy if you’re getting attention, but you aren’t going to start at the top. Very few make it, and I’m proof that it doesn’t last long. But if you’re going to spend your whole life chasing fame, you’re going to be a very unhappy person. With everything I’ve been through, I’ve learned this one thing: Fame and money aren’t worth it if you have nothing else in your life.

I turn my back on her and head for the register. Maybe it’s easy for me to tell others that money doesn’t matter. I have plenty of it, but I know that no matter what my financial situation was, I’d paint. Even if I was living in a dirty studio apartment and eating instant soup, I’d paint.

Because that’s what makes me happy. And I deserve to be happy. Everybody does, even Sophie. But it’s up to each of us to find our own way.

I feel like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I spend my mornings studying language arts, social studies, and science. The afternoon, I tackle math. But at night, I paint.

I think all the studying has freed up my painting, and the meeting with Mr. Samuels has given me the confidence to know that I’m moving in the right direction. I’m no longer fixed on getting everything “right” or being precise. I guess spending all day staring at textbooks has, in a weird way, made me looser.

I think of all the personas I’ve had: Child Actor, Washed-Up Child Actor, Teen Semi-Heartthrob, High School Student…. But with the paintbrush in my hand and my mind clear, for the first time I feel like Carter Harrison: Artist. And that fact doesn’t embarrass or scare me.

The red paint I’ve dipped my brush in starts to drip and I let some of the paint go on the canvas. I’m not sure what direction this painting is going, but it’s kind of like my life right now.

A work in progress.

And the possibilities are endless.

Emme

After weeks — okay, months, maybe even years — of practicing, it’s finally time.

My Berklee audition is first. I’m somewhat grateful since Berklee has an acceptance rate of thirty-five percent, compared to Juilliard’s eight percent. Like either of those odds are in anybody’s favor.

I decided to do the audition in New York instead of heading up to the Boston campus. While I’m used to sitting in the hallway, waiting for my name to be called out, the nerves are stronger than anything that I experienced at CPA.

I think about how much easier it would be if the guys were here.

I think about Ben, who doesn’t have to deal with auditions anymore.

I think about Jack, who is auditioning for CalArts today.

I think about Ethan, who had his Berklee audition yesterday.

I think about Carter, who is spending the weekend taking the GED.

What I don’t want to think about is next weekend. Doing this all over again, but at Juilliard. And then doing it again for Boston Conservatory, the Manhattan School of Music, and the San Francisco Conservatory.

Fortunately, most of the schools I applied to were part of the Unified Application for Music and Performing Arts Schools, so I only had to do one application for them. But there are auditions for each one.

Maybe by the end, I’ll no longer get nervous.

“Emme Connelly.”

My name is called out and the taste of bile stings my throat.

Or not.

The school week flies by. I don’t think about anything but the Juilliard audition. My audition is a little over two hours after Ethan’s. We go to a café near Lincoln Center for breakfast, but I can’t eat. Every time I try to put something in my stomach, it either comes back up or tastes like dust.

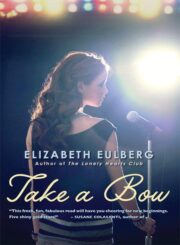

"Take a Bow" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Take a Bow". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Take a Bow" друзьям в соцсетях.