‘Let me tell you, Tom, that foreign travel is a necessary part of every young man’s education!’ said the Dowager severely.

‘Yes, ma’am,’ said Tom. He added more hopefully: ‘Only I daresay my father would not wish me to go!’

‘Nonsense! Your father is a sensible man, and he told me he thought it time you got a little town bronze. Depend upon it, he can very well spare you for a week or two. I shall write him a letter, and you may take it to him. Now, boy, don’t be tiresome! If you don’t care to go on your own account you may do so on Phoebe’s.’

The matter being put thus to him Tom said that of course he was ready to do anything for Phoebe. Then he thought that this was not quite polite, so he added, blushing to the roots of his hair, that it was excessively kind of her la’ship, he was persuaded he would enjoy himself excessively, and his father would be excessively obliged to her. Only perhaps he ought to mention that he knew very little French, and had not before been out of England.

These trifling objections waved aside, the Dowager explained why she was so suddenly leaving London. She asked him if Phoebe had told him of the previous night’s happenings. That brought the grave look back into his face. He said: ‘Yes, she has, ma’am. It’s the very deuce of a business, I know, and I don’t mean to say that it wasn’t wrong of her to have written all that stuff about Salford, but it was just as wrong of him to have given her a trimming in public! I-I call it a dashed ungentlemanly thing to have done, because he must have meant to sink her to the ground! What’s more, I wouldn’t have thought it of him! I thought he was a first rate sort of a man-a regular Trojan! Oh lord, if only she had told him! I had meant to have visited him, too! I shan’t now, of course, for whatever she did I’m on Phoebe’s side, and so I should tell him!’

‘No, I shouldn’t visit him just yet,’ said Georgiana, regarding him with warm approval. ‘He is a Trojan, but I am afraid he may be in a black rage. He wouldn’t otherwise have behaved so improperly last night, you know. Poor Phoebe! Is she very much afflicted?’

‘Well, she was in the deuce of a way when I came,’ replied Tom. ‘Shaking like a blancmanger! She does, you see, when she’s been overset, but she’s better now, though pretty worn down. The thing is, Lady Ingham, she wants me to take her home!’

‘Wants you to take her home?’ exclaimed the Dowager. ‘Impossible! She cannot want that!’

‘Yes, but she does,’ Tom insisted. ‘She will have it she has disgraced you as well as herself. And she says she had rather face Lady Marlow than anyone in London, and at all events she won’t have to endure Austerby for long, because as soon as those publisher fellows hand over the blunt-I mean, as soon as they pay her!-she and Sibby will live together in a cottage somewhere. She means to write another novel immediately, because she has been offered a great deal of money for it already!’

The disclosure of this fell project acted alarmingly on the Dowager. To Tom’s dismay she uttered a moan, and fell back against her cushions with her eyes shut. Resuscitated by smelling salts waved under her nose, and eau-de-Cologne dabbed on her brow, she regained enough strength to tell Tom to fetch Phoebe to her instantly. Georgiana, catching the doubtful glance he cast at her, picked up her gloves and her reticule, and announced that she would take her leave. ‘I expect she feels she had rather not meet me, doesn’t she? I perfectly understand, but pray give her my love, Mr. Orde, and assure her that I am still her friend!’

The task of persuading Phoebe to view with anything less than revulsion the prospect of being transported from the fashionable world of London to that of Paris was no easy one. In vain did the Dowager assure her that if some ill-natured gossip should have written the story of her downfall to a friend in Paris it could be denied; in vain did she promise to present her to King Louis; in vain did she describe in the most glowing terms the charm and gaiety of French society: Phoebe shuddered at every treat held out to her. Tom, besought by the Dowager to try what he could achieve, was even less successful. Adopting a bracing note, he told Phoebe that she must shake off her blue devils, and try to come about again.

‘If only I might go home!’ she said wretchedly.

That, said Tom, was addlebrained, for she would only mope herself to death at Austerby. What she must do was to put the affair out of her head-though he thought she should perhaps write a civil letter of apology to Salford from Paris. After that she could be comfortable, for she would not be obliged to meet him again for months, if Lady Ingham hired a house in Paris, as she had some notion of doing.

But the only effect of this heartening speech was to send Phoebe out of the room in floods of tears.

It was left to the Squire to bring her to a more submissive frame of mind, which he did very simply, by telling her that she owed it to her grandmother, after causing her so much trouble, to cheer up and do as she wished. ‘For it’s my belief,’ said the Squire shrewdly, ‘that she wants to go as much for her own sake as yours. I must say I should like Tom to get a glimpse of foreign parts, too.’

That settled it: Phoebe would go to Paris for Grandmama’s sake, and try very hard to enjoy it. Her subsequent efforts to appear cheerful were heroic, and quite enough (said Tom) to throw the whole party into the dismals.

Between Phoebe’s brave front and Muker’s undisguised gloom the Dowager might well have abandoned the scheme had it not been for the support afforded her by young Mr. Orde. Having consented to go with her, Tom resigned himself with a good grace, and threw himself into all the business of departure with so much energy and good-humour that he soon began to rival Phoebe in the Dowager’s esteem. With a little assistance from the Squire, before that excellent man returned to Somerset, he grappled with passports, customs, and itineraries; ascertained on which days the mails were made up for France, and on which days the packets sailed; calculated how much money would be needed for the journey; and got by heart such French phrases as he thought would be most useful. A Road Book was his constant companion; and whenever he had occasion to pull out his pocket-book a shower of leaflets accompanied it.

It did not take him long to discover that the task of conveying Lady Ingham on a journey was no sinecure. She was exacting and she changed her mind almost hourly. No sooner had he gone off with her old coachman to inspect her travelling carriage (kept by her longsuffering son in his coach-house and occupying a great deal of space which he could ill spare) than she decided that it would be better to travel post. Off went Tom in a hack to arrange for the hire of a chaise, only to find on his return to Green Street that she had remembered that since Muker would occupy the forward seat they would be obliged to sit three behind her, which would be intolerable.

‘I am afraid,’ said Lord Ingham apologetically, ‘that you have taken a troublesome office upon yourself, my boy. My mother is rather capricious. You mustn’t allow her to wear you to death. I see you are lame, too.’

‘Oh, that’s nothing, sir!’ said Tom cheerfully. ‘I just take a hack, you know, and rub on very well!’

‘If I can be of assistance,’ said Lord Ingham, in a dubious tone, ‘you-er-you must not hesitate to apply to me.’

Tom thanked him, but assured him that all was in a way to be done. He could not feel that Lord Ingham’s assistance would expedite matters, since he knew by now that the Dowager invariably ran counter to his advice, and was exasperated by his rather hesitant manners. Lord Ingham looked relieved, but thought it only fair to warn Tom that there was a strong probability that the start would be delayed for several days, owing to the Dowager’s having decided at the last minute that she could not leave town without a gown that had not yet been sent home by her dressmaker, or some article that had been put away years before and could not now be found.

‘Well, sir,’ said Tom, grinning, ‘she had the whole set of ‘em turning the house out of the windows to find some cloak or other when I left, but I’ll bring her up to scratch: see if I don’t!’

Lord Ingham shook his head, and when he repaired to Green Street on the appointed day to bid his parent a dutiful farewell it was in the expectation of finding the plans changed again, and everything at odds. But Tom had made his word good. The old-fashioned coach stood waiting, piled high with baggage; and Lord Ingham entered the house to find the travellers fully equipped for the adventure, and delayed only by the Dowager’s sudden conviction that her curling tongs had been forgotten, which entailed the removal of everything from her dressing case, Muker having packed them at the bottom of it.

Lord Ingham, eyeing young Mr. Orde with respect, was moved to congratulate him. Young Mr. Orde then confided to him that it had been a near-run thing, her la’ship having been within ames-ace of crying off as late as yesterday, when the weather took a turn for the worse. ‘But I managed to persuade her, sir, and I think I shall be able to get her aboard Thursday’s packet all right and tight,’ said optimistic Tom.

Lord Ingham, casting an apprehensive glance at the hurrying clouds, thought otherwise, but refrained from saying so.

20

Lord Ingham was right. The first glimpse caught of the sea afforded the Dowager a view of tossing grey waters, flecked with foam; and long before she was handed down from the coach at the Ship Inn she had informed Tom that a regiment of Guards would not suffice to drag her on board the packet until the wind had abated. Two days of road travel (for to avoid fatigue she had elected to spend one night at Canterbury) had given her the headache; and during the rest of the journey she became steadily more snappish. Her temper was not improved, on alighting at Dover, by having the hat nearly snatched from her head by a gust of wind; and it seemed for several minutes as though she might re-enter the coach then and there, and return to London. Fortunately Tom had written to bespeak accommodation for the party; and the discovery that the best bedchamber had been reserved for her, and the best parlour with fires kindled in both, mollified her. A dose of the paregoric prescribed by Sir Henry Halford, followed by an hour’s rest, and an excellent dinner did much to restore her, but when Tom told her that the packet had sailed for Calais that day as usual, from which circumstance it might be inferred that no danger of shipwreck attended the passage, she replied discouragingly: ‘Exactly what I am afraid of!’

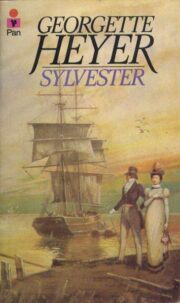

"Sylvester" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester" друзьям в соцсетях.