“It’s too late!” he said, “I could have scotched the scandal! Instead—” He broke off, and looked keenly at her. “I can’t recall. Was my busy aunt Louisa at the Castlereaghs’ ball?”

“Yes, dearest.”

“I see.” He got up jerkily, and moved to the fireplace, standing with his head turned a little away from the Duchess. “I am sure she told you what happened there.”

“An unfortunate affair,” said the Duchess calmly. “You were naturally very angry.”

“There was no excuse for what I did. I knew her dread of—I can see her face now!”

“What is she like, Sylvester?” She waited, and then prompted: “Is she pretty?”

He shook his head. “No. Not a beauty, Mama. When she is animated, I believe you would consider her taking.”

“I collect, from all I have heard, that she is unusual?”

“Oh, yes, she’s unusual!” he said bitterly. “She blurts out whatever may come into her head; she tumbles from one outrageous escapade into another; she’s happier grooming horses and hobnobbing with stable-hands than going to parties; she’s impertinent; you daren’t catch her eye for fear she should start to giggle; she hasn’t any accomplishments; I never saw anyone with less dignity; she’s abominable, and damnably hot at hand, frank to a fault, and—a darling!”

“Should I like her, Sylvester?” said the Duchess her eyes on his profile.

“I don’t know,” he said, a suggestion of impatience in his voice. “I daresay—I hope so—but you might not. How can I possibly tell? It’s of no consequence: she won’t have me.” He paused, and then said, as though the words were wrung out of him: “O God, Mama, I’ve made such a mull of it! What am I to do?”

28

After a troubled night, during which she was haunted, waking or dreaming, by all the appalling events of the previous day, which had culminated in a shattering scene with Lady Ingham, Phoebe awoke to find the second housemaid pulling back the blinds, and learned from her that the letter lying on her breakfast-tray had been brought round by hand from Salford House not ten minutes earlier. The housemaid was naturally agog with curiosity, but any expectation she had of being made the recipient of an interesting confidence faded before the seeming apathy with which Miss Phoebe greeted her disclosure. All Miss Phoebe wanted was a cup of tea; and the housemaid, after lingering with diminishing hope for a few minutes, left her sitting up in bed, and sipping this restorative.

Once alone, Phoebe snatched up the letter, and tore it open. She looked first at the signature. Elizabeth Salford was what met her eyes, and drew from her a gasp of fright.

But there was nothing in the letter to make her tremble. It was quite short, and it contained no hint of menace. The Duchess wished very much not only to make the acquaintance of a loved friend’s daughter, but also to thank her for the care she had taken of her grandson. She hoped that Phoebe would be able, perhaps, to visit her that day, at noon, when she would be quite alone, and they could talk without fear of interruption.

Rather a gratifying letter for a modest damsel to receive, one would have supposed, but the expression on Phoebe’s face might have led an observer to conclude that she was reading a tale of horror. Having perused it three times, and failing to detect in it any hidden threat, Phoebe fixed her attention on the words: I shall be quite alone, and carefully considered them. If they were meant to convey a message it was hard to see how this could be anything but one of reassurance; but if this were so, Sylvester must have told his mother—what?

Thrusting back the bedclothes Phoebe scrambled out of bed and into her dressing-gown, and pattered down the stairs to her grandmother’s room. She found the afflicted Dowager alone, and held out the letter to her, asking her in a tense voice to read it.

The Dowager had viewed her unceremonious entrance with disfavour, and she at once said in feeble accents: “Oh, heaven! what now?” But this ejaculation was not wholly devoid of hope, since she too had been told whence had come Miss Phoebe’s letter. Poor Lady Ingham had slept quite as badly as her granddaughter, for she had had much to puzzle her. At first determined to send Phoebe packing back to Somerset, she had been considerably mollified by the interesting intelligence conveyed to her (as Sylvester had known it would be) by Horwich. She had thought it promising, but further reflection had sent her spirits down again: whatever might be Sylvester’s sentiments, Phoebe bore none of the appearance of a young female who had either received, or expected to receive, a flattering offer for her hand. Hope reared its head again when a letter from Salford House was thrust upon her; like Phoebe, she looked first at the signature, and was at once dashed down. “Elizabeth!” she exclaimed, in a flattened voice. “Extraordinary! She must have come on the child’s account, I suppose. I only trust it may not be the death of her!”

Phoebe watched her anxiously while she mastered the contents of the letter, and when it was given back to her said imploringly: “What must I do, ma’am?”

The Dowager did not answer for a moment. There was food for deep thought in the Duchess’s letter. She gazed inscrutably before her, and the question had to be repeated before she said, with a slight start: “Do? You will do as you are bid, of course! A very pretty letter the Duchess has writ you, and why she should have done so—but she hasn’t, one must assume, read that abominable book!”

“She has read it, ma’am,” Phoebe said. “It was she who gave it to Salford. He told me so himself.”

“Then he cannot have told her who wrote it,” said the Dowager. “That you may depend on, for she dotes on Sylvester! If only she could be persuaded to take you up—But someone is bound to tell her!”

“Grandmama, I must tell her myself!” Phoebe said.

The Dowager was inclined to agree with her, but the dimming of a future which had seemed to become suddenly so much brighter vexed her so much that she said crossly: “You must do as you please! I cannot advise you! And I beg you won’t ask me to accompany you to Salford House, for I am quite unequal to any exertion! You may have the landaulet, and, for heaven’s sake, Phoebe, try at least to appear the thing! You must wear the fawn-coloured silk, and the pink—no, it will make you look hideously sallow! It will have to be the straw with the brown ribands.”

Thus arrayed, Miss Marlow, shortly before noon, stepped into the landaulet, as pale as if it had been a tumbrel and her destination the gallows.

Such was the state of her mind that she would not have been surprised, on arrival at Salford House, to have been confronted by a host of Raynes, all pointing fingers of condemnation at her. But the only persons immediately visible were servants, who seemed, with the exception of the butler, whose aspect was benevolent, to be perfectly uninterested. It was well for her peace of mind that she did not suspect that every member of the household who had the slightest business in the hall had contrived to be there to get a glimpse of her. Such an array of footmen seemed rather excessive, not to say pompous, but if that was the way Sylvester chose to run his house it was quite his own affair.

The benevolent butler conducted her up one pair of stairs. Her heart was thumping hard, and she felt unusually breathless, both of which disagreeable symptoms would have been much aggravated had she known how many interested persons were watching from hidden points of vantage every step of her progress. No one could have told whence had sprung the news that his grace had chosen a leg-shackle at last, and was finding his path proverbially rough, but everyone knew it, from the agent-in-chief down to the humblest kitchen-porter; and an amazing number of these persons contrived to be spectators of Miss Marlow’s arrival. Most of them were disappointed in her; but Miss Penistone and Button found nothing amiss, one of these ladies being sentimentally disposed to think any damsel of dear Sylvester’s choice a paragon, and the other regarding her in the light of a Being sent from on high to preserve her darling from death by shipwreck, surfeit, neglect, or any other of the disasters which might have been expected to strike down an infant of tender years taken to outlandish parts without his nurse.

Phoebe heard her name announced, and stepped across the threshold of the Duchess’s drawing-room. The door closed behind her, but instead of walking forward she stood rooted to the ground, staring across the room at her hostess. A look of naïve surprise was in her face, and she so far forgot herself as to utter an involuntary: “Oh—!”

No one had ever told her how pronounced was the resemblance between Sylvester and his mother. At first glance it was startling. At the second one perceived that the Duchess had warmer eyes than Sylvester, and a kinder curve to her lips.

Before Phoebe had assimilated these subtle differences an amused laugh escaped the Duchess, and she said: “Yes, Sylvester has his eyebrows from me, poor boy!”

“Oh, I beg your pardon, ma’am!” Phoebe stammered, much confused.

“Come and let me look at you!” invited the Duchess. “I daresay your grandmother may have told you that I have a stupid complaint that won’t let me get out of my chair.”

Phoebe stayed where she was, clasping both hands tightly on her reticule. “Ma’am—I am very much obliged to your grace for having—honoured me with this invitation—but I must not accept your hospitality without telling you—that it was I who wrote—that dreadful book!”

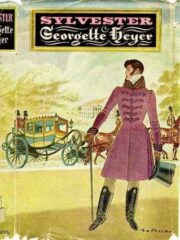

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.