As yet unperceived, Phoebe remained by the window, watching with some amusement Edmund’s ecstatic welcome to his wicked uncle. She was not so very much surprised, though she had not expected him to be cast into quite such transports of delight. If anything surprised her it was Sylvester’s amused acceptance of Edmund’s violent hug. He did not look at all like a man who disliked children; and he did not look at all like the man who had said such terrible things to her at Lady Castlereagh’s ball. That image, which had so painfully obsessed her, faded, and with it the embarrassment which had made her dread his arrival almost as much as she had hoped for it.

“Tell that Bad Man I am not his little boy!” begged Edmund. “Mama says I don’t belong to you, Uncle Vester, but I do, don’t I?”

This was uttered so passionately that Phoebe could not help laughing. Sylvester looked round quickly, and saw her. Something leaped in his eyes; she had the impression that he was going to start towards her. But the look vanished in a flash, and he did not move. The memory of their last meeting surged back, and she knew herself to be unforgiven.

He did not speak immediately, but set Edmund on his feet. Then he said: “A surprise, Miss Marlow—though I daresay I should have guessed, had I put myself to the trouble of considering the matter, that I should be very likely to find you here.”

His voice was level, concealing all trace of the emotions seething in his breast. They were varied, but uppermost was anger: with her for having, as he supposed, assisted in the abduction of Edmund; with himself for having, for an unthinking moment, been so overjoyed to see her. That made him so furious that he would not open his lips until he could command himself. He had been trying, ever since the night of the ball, to banish all thought of her from his mind. This had not been possible, but by dint of dwelling on the injury she had done him he had supposed he had at least cured himself of his most foolish tendre for her. It had been an easy task to remember only her shameful conduct, for the wound she had inflicted on him could not be forgotten. She had held him up as a mockery to the world: that in itself was an offence, but if the portrait she had drawn of him had been unrecognizable he could have forgiven her. He had thought it so, but when he had turned to his mother, who had given the book to him to read, prepared to shrug it off, to tell her that it was too absurd to be worth a moment’s indignation, he had seen in her face not indignation but trouble. He had been so much shocked that he had exclaimed: “This is not a portrait of me! Oh, I grant the eyebrows, but nothing else!” She had replied: “It is overdrawn, of course.” It had been a full minute before he could bring himself to say: “Am I like this contemptible fellow, then? Insufferably proud, so indifferent—so puffed up in my own esteem that—Mama!” She had said quickly, stretching out her hand to him: “Never to me, Sylvester! But I have sometimes wondered—if you had grown to be a little—uncaring—towards others, perhaps.”

He had been stricken to silence, and she had said no more. There had been no need: Ugolino was a caricature, but a recognizable one; and because he was forced to believe this, his resentment, irrationally but inevitably in one of his temperament, blazed into such rage as he had never known before.

As he looked at Phoebe across the coffee-room he knew her for his evil genius. She had embroiled him in her ridiculous flight from her home; she had led him to pay her such attentions as had brought them both under the gaze of the interested ton. He forgot that his original intention had been to win her regard only to make her regret her rejection of his suit: he had forgotten it long ago. He knew that her book must have been written before she had become so well acquainted with him, but she had neither stopped its publication nor warned him of it. She had been the cause of his having behaved, at that accursed ball, in a manner as unworthy of a man of breeding as anything could well have been. What had made him do it he would never know. It had been his intention to treat her with unswerving civility. He had meant to make no mention, then or thereafter, of her book, but to have conducted himself towards her in such a way as must have shown her how grossly she had misjudged him. He had been sure that he had had himself well in hand; and yet, no sooner was his arm round her waist and his hand clasping hers than his anger and a sense of bitter hurt had mastered him. She had broken from his hold in tears, and he had been furious with her for doing it, because he knew he had brought that scene on himself. And now he found her in Abbeville, laughing at him. He had never doubted that it was she who had put the notion of a flight from England into Ianthe’s head, but he had believed she had not meant to do so. It was now borne in upon him that she must have been throughout in Ianthe’s confidence.

Knowing nothing of what was in his mind Phoebe watched him in perplexity. After a long pause she said, in a constricted tone: “I collect you have not received my letter, Duke?”

“I have not had that pleasure. How obliging of you to have written to me! To inform me of this affair, no doubt?”

“I could have no other reason for writing to you.”

“You should have spared yourself the trouble. Having read your book, Miss Marlow, it was not difficult to guess what had happened. I own it did not occur to me that you were actually aiding my sister-in-law, but of course it should have. When I discovered that she had taken Edmund away without his nurse I ought certainly to have guessed how it must be. Are you filling that position out of malice, or did you feel, having made London too hot to hold you, that it offered you a chance of escape?”

As she listened to these incredible words Phoebe passed from shock to an anger as great as his, and not as well concealed. He had spoken in a light, contemptuous voice; she could not keep hers from shaking when she retorted: “From malice!”

Before he could speak again Edmund said, in an uneasy tone: “Phoebe is my friend, Uncle Vester! Are—are you vexed with her? Please don’t be! I love her next to Keighley!”

“Do you, my dear?” said Phoebe. “That is praise indeed! No one is vexed: your uncle was funning, that’s all!” She looked at Sylvester, and said as naturally as she could: “You must wish to see Lady Ianthe, I daresay. I regret that she is indisposed—is confined to her bed, in fact, with an attack of influenza.”

His colour was rather heightened; for he had forgotten that Edmund was still clinging to his hand, and was annoyed with himself for having been betrayed into impropriety. He said only: “I trust Fotherby is not similarly indisposed?”

“No, I believe he is sitting with Lady Ianthe. I will inform him of your arrival directly.” She smiled at Edmund. “Shall we go and see if that cake Madame said she would bake for your supper is done yet?”

“I think I will stay with Uncle Vester,” Edmund decided.

“No, go with Miss Marlow. I am going to talk to Sir Nugent,” said Sylvester.

“Will you grind his bones?” asked Edmund hopefully.

“No, how should I be able to do that? I’m not a giant, and I don’t live at the top of a beanstalk. Go, now.”

Edmund looked regretful, but obeyed. Sylvester cast his driving-coat over a chair, and walked over to the fire.

He had not long to wait for Sir Nugent. That exquisite came into the room a very few minutes later, exclaiming: “Well, upon my soul! I declare I was never more surprised in my life! How do you do? I’m devilish glad to see your grace!”

This entirely unexpected greeting threw Sylvester off his balance. “Glad to see me?” he repeated.

“Devilish glad to see you!” corrected Sir Nugent. “Ianthe was persuaded you wouldn’t follow us. Thought you wouldn’t wish to kick up a dust. I wouldn’t have betted on it, though I own I didn’t expect you to come up with us so quickly. Damme, I congratulate you, Duke! No flourishing, no casting, and how you picked up the scent the lord only knows!”

“What I want, Fotherby, is not your congratulation, but my ward!” said Sylvester. “You will also be so obliging as to explain to me what the devil you meant by bringing him to France!”

“Now, there,” said Sir Nugent frankly, “you have me at Point-Non-Plus, Duke! I fancy Nugent Fotherby ain’t often at a loss. I fancy you’d be told, if you was to ask anyone, that Nugent Fotherby is as shrewd as he can hold together. But that question is a doubler. I don’t mind telling you that every time I ask myself why the devil I brought that boy to France I’m floored. It’s a great relief to me to hear you say you want him—you did say so, didn’t you?”

“I did, and I will add that I am going to have him!”

“I take your word for that,” Sir Nugent said. “Nugent Fotherby ain’t the man to doubt a gentleman’s honour. Let us discuss the matter!”

“There is nothing whatsoever to discuss!” said Sylvester, almost grinding his teeth.

“I assure your grace discussion is most necessary,” said Sir Nugent earnestly. “The boy has a mother! She is not at the moment in plump currant, you know. She must be cherished!”

“Not by me!” snapped Sylvester.

“Certainly not! If I may say so—without offence, you understand—it’s not your business to cherish her: never said you would! I daresay, being a bachelor, you may not know it, but I did. I’m not at all sure I didn’t swear it: it sounded devilish like an oath to me.”

“If all this is designed to make me relinquish my claim on Edmund—”

“Good God, no!” exclaimed Sir Nugent, blenching. “You mistake, Duke! Only too happy to restore him to you! You know what I think?”

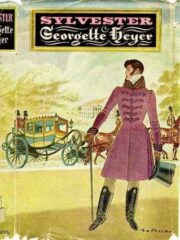

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.