Edmund, who was seated beside Phoebe at the table, a napkin knotted round his neck, looked up at this. “You wish to kill Mama,” he stated.

“Eh?” ejaculated Sir Nugent. “No, dash it—! You can’t say things like that!”

“Mama said it,” replied Edmund. “On that boat she said it.”

“Did she? Well, but—well, what I mean is it’s a bag of moonshine! Devoted to her! Ask anyone!”

“And you told lies, and—”

“You eat your egg and don’t talk so much!” intervened Tom, adding in an undervoice to his perturbed host: “I shouldn’t argue with him, if I were you.”

“Yes, that’s all very well,” objected Sir Nugent. “He don’t go about telling people you are a regular hedge-bird! Where will he draw the line, that’s what I should like to know?”

“When Uncle Vester knows what you did to me he will punish you in a terrible way!” said Edmund ghoulishly.

“You see?” exclaimed Sir Nugent. “Now we shall have him setting it about I’ve been ill-using him!”

“Uncle Vester,” pursued his small tormentor, “is the terriblest person in the world!”

“You know, you shouldn’t talk like that about your uncle,” Sir Nugent said earnestly. “I don’t say I like him myself, but I don’t go about saying he’s terrible! Top-lofty, yes, but—”

“Uncle Vester doesn’t wish you to like him!” declared Edmund, very much flushed.

“I daresay he don’t, but if you mean he’ll call me out—well, I don’t think he will. Mind, if he chooses to do so—”

“Lord, Fotherby, don’t encourage him!” said Tom, exasperated.

“Uncle Vester will grind your bones!” said Edmund.

“Grind my bones?” repeated Sir Nugent, astonished. “You’ve got windmills in your head, boy! What the deuce should he do that for?”

“To make him bread,” responded Edmund promptly.

“But you don’t make bread with bones!”

“Uncle Vester does,” said Edmund.

“That’s enough!” said Tom, trying not to laugh. “It’s you that’s telling whiskers now! You know very well your uncle doesn’t do any such thing, so just you stop pitching it rum!”

Edmund, apparently recognizing Tom as a force to be reckoned with, subsided, and applied himself to his egg again. But when he had finished it he shot a speculative glance at Tom under his curling lashes, and said: “P’raps Uncle Vester will nap him a rum ’un.”

Tom gave a shout of laughter, but Phoebe scooped Edmund up and bore him off. Edmund, pleased by the success of his audacious sally, twinkled engagingly at Tom over her shoulder, but was heard to say before the door closed: “We Raynes do not like to be carried!”

The party left for Abbeville an hour later, in impressive style. Sir Nugent having loftily rejected a suggestion that the heavy baggage should be sent to Paris by the roulier, no fewer than four vehicles set out from the Lion d’Argent. The velvet-lined chariot bearing Sir Nugent and his bride headed the cavalcade; Phoebe, Tom, and Edmund followed in a hired post-chaise; and the rear was brought up by two cabriolets, one occupied by Pett and the Young Person hired to wait on my lady, and the other crammed with baggage. Quite a number of people gathered to watch this departure, a circumstance that seemed to afford Sir Nugent great satisfaction until a jarring note was introduced by Edmund, who strenuously resisted all efforts to make him enter the chaise, and was finally picked up, kicking and screaming, by Tom, and unceremoniously tossed on to the seat. As he saw fit to reiterate at the top of his voice that his father-in-law was a Bad Man, Sir Nugent fell into acute embarrassment, which was only alleviated when Tom reminded him that the interested onlookers were probably unable to understand anything Edmund said.

Once inside the chaise Edmund stopped screaming. He bore up well for the first stages, beguiled by a game of Travelling Piquet. But as the number of flocks of geese, parsons riding grey horses, or old women sitting under hedges was limited on the post-road from Calais to Boulogne, this entertainment soon palled, and he began to be restive. By the time Boulogne was reached Phoebe’s repertoire of stories had been exhausted, and Edmund, who had been growing steadily more silent, said in a very tight voice that he felt as sick as a horse. He was granted a respite at Boulogne, where the travellers stopped for half an hour to refresh, but the look of despair on his face when he was lifted again into the chaise moved Tom to say, over his head: “I call it downright cruel to drag the poor little devil along on a journey like this!”

At Abbeville, which they reached at a late hour, Sinderby was awaiting them at the best hotel with tidings which caused Sir Nugent to suffer almost as much incredulity as vexation. Sinderby had to report failure. He had been unable to persuade the best hotel’s proprietor either to eject his other clients from the premises, or to sell the place outright to Sir Nugent. “As I ventured, sir, to warn you would be the case,” added Sinderby, in a voice wholly devoid of expression.

“Won’t sell it?” said Sir Nugent. “You stupid fellow, did you tell him who I am?”

“The information did not appear to interest him, sir.”

“Did you tell him my fortune is the largest in England?” demanded Sir Nugent.

“Certainly, sir. He desired me to offer you his felicitations.”

“He must be mad!” ejaculated Sir Nugent, stunned.

“It is curious that you should say so, sir,” replied Sinderby. “Precisely what he said—expressing himself in French, of course.”

“Well, upon my soul!” said Sir Nugent, his face reddening with anger. “That to me? I’ll have the damned ale-draper to know I ain’t in the habit of being denied! Go and tell him that when Nugent Fotherby wants a thing he buys it, cost what it may!”

“I never listened to such nonsense in my life!” said Phoebe, unable any longer to restrain her impatience. “I wish you will stop brangling, Sir Nugent, and inform me whether we are to put up here, or not! It may be nothing to you, but here is this unfortunate child nearly dead with fatigue, while you stand there puffing off your consequence!”

Sir Nugent was too much taken aback by this sudden attack to be able to think of anything to say; Sinderby, regarding Miss Marlow with a faint glimmer of approval in his cold eyes, said: “Bearing in mind, sir, your instructions to me to provide for her ladyship the strictest quiet, I have arranged what I trust will be found to be satisfactory accommodation in a much smaller establishment. It is not a resort of fashion, but its situation, which is removed from the centre of the town, may render it agreeable to her ladyship. I am happy to say that I was able to persuade Madame to place the entire inn at your disposal, sir, for as many days as you may desire it, on condition that the three persons she was already entertaining were willing to remove from the house.”

“You aren’t going to tell us that they were willing, are you?” demanded Tom.

“At first, sir, no. When, however, they understood that the remainder of their stay in Abbeville—I trust not a protracted one—would be spent by them in the apartments I had engaged at this hotel for Sir Nugent, and at his expense, they expressed themselves as being enchanted to fall in with his wishes. Now, sir, if you will rejoin her ladyship in the travelling chariot, I will escort you to the Poisson Rouge.”

Sir Nugent stood scowling for a moment, and pulling at his underlip. It was left to Edmund to apply the goad: “I want to go home!” announced Edmund fretfully. “I want my Button! I’m not happy!”

Sir Nugent started, and without further argument climbed back into the chariot.

When he saw the size and style of the Poisson Rouge he was so indignant that had it not been for Ianthe, who said crossly that rather than go another yard she would sleep the night in a cowbyre, another altercation might have taken place. As she was handed tenderly down the steps, Madame Bonnet came out to welcome her eccentric English guests, and fell into such instant raptures over the beauty of miladi and her enchanting little son that Ianthe was at once disposed to be very well pleased with the inn. Edmund, glowering upon Madame, showed a tendency to hide behind Phoebe, but when a puppy came frisking out of the inn his brow cleared magically, and he said: “I like this place!”

Everyone but Sir Nugent liked the place. It was by no means luxurious, but it was clean, and had a homelike air. The coffee-room might be furnished only with benches and several very hard chairs, but Ianthe’s bedchamber looked out on to a small garden and was perfectly quiet, which, as she naively said, was all that signified. Moreover, Madame, learning of her indisposition, not only gave up her own featherbed to her, but made her a tisane, and showed herself to be in general so full of sympathy that the ill-used beauty, in spite of aching head and limbs, began to feel very much more cheerful, and even expressed a desire to have her child brought to kiss her before he went to bed. Madame said she had a great envy to witness this spectacle, having been forcibly reminded of the Sainte Vierge as soon as she had set eyes on the angelic visages of miladi and her lovely child.

A discordant note was struck by Phoebe, who entered upon this scene of ecstasy only to tell Ianthe bluntly that she had not brought Edmund with her because she had a suspicion that what ailed his doting mother was nothing less than a severe attack of influenza. “And if he were to take it from you, after all he has been made to undergo, it would be beyond everything!” said Phoebe.

Ianthe achieved a wan, angelic smile, and said: “You are very right, dear Miss Marlow. Poor little man! Kiss him for me, and tell him that Mama is thinking of him all the time!”

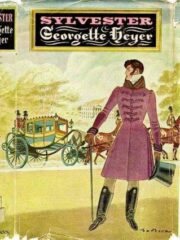

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.